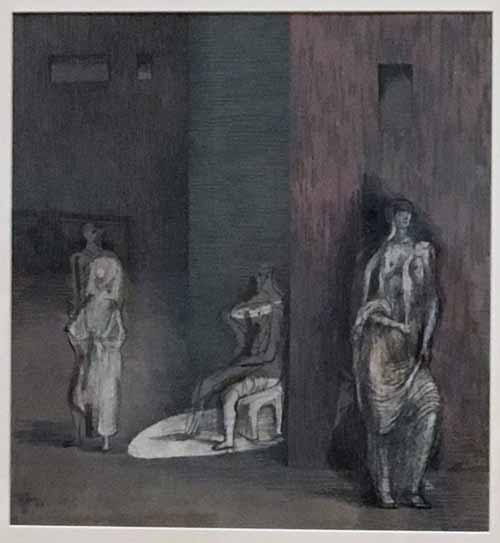

Henry Moore

British, 1898 – 1986

Three Figures in a Setting, 1942

ink and waxed crayon on grey paper

17 3/4 × 16 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Wright S. Ludington

1945.6.11

Henry Moore in his study, photo by Gemma Levine

COMMENTS

As the war was not conducive to producing sculpture, Moore turned his formidable creative energy to drawing, a genre he interpreted in its widest form. As well as pencil and pen and ink, monochrome washes and watercolor, he employed a range of wax crayons, which are resistant to water based media, thus giving a rich textural quality to his work. 1942 was a particularly productive year; he produced over 100 studies of working coal miners, together with many ideas for sculpture, particularly of reclining figures, as well as a series of large-format studies such as this, in which he depicted groups of figures in stark, Kafkaesque interiors, which are redolent of prison cells or Gordon’ Craig’s most avant-garde stage sets.

Moore was in Englishman living outside London. One night during WWII, he and his wife were caught in an air raid while in London, and had to overnight in a shelter. The British were using the subway platforms as their shelters, and the encounter was a very moving experience for Henry Moore. For Moore, when he descended to the shelter, he saw rows and rows of Henry Moore sculptures; the two favorite themes for his sculpture were mother and child, and the reclining figure. In the underground that was exactly what he saw. As the air raids occurred at night, and the underground was cold, those seeking shelter were all wrapped in blankets. These blankets become the drapery in the drawings. These sleeping, huddled figures are seen from a low viewpoint, which is disturbing. Though safe below ground, they are preoccupied with what is happening above them. Moore also uses color for emotional effect, and here he has used red, the color for danger and for fires, thereby adding to the feeling of tension. Moore has used many mediums - pen, pencil, charcoal, and watercolor – creating a further sense of depth to his drawings. All of Moore’s sculptures originated as drawings, so the drawings were both functional and revealing. It is clear in looking at Moore’s drawings that a sculptor drew them. Moore had to stop making metal sculptures due to the war effort, so he concentrated on his drawings, Studies for Sculpture. He felt that this was good exercise, exploring and defining his feelings for sculpture. His concept of space was important. Moore felt that the space around his sculpture was as important as the sculpture itself. Furthermore, the holes he introduced in his works allowed him to explore the space within the work. All of this created a push-pull or positive-negative effect with his sculptures and their surrounding space. Moore also felt strongly about asymmetry, as can be seen – each side is different from the other.

-From the docent office files

Henry Moore was the most important British sculptor of the 20th century, and the most popular and internationally celebrated sculptor of the post-war period. Non-Western art was crucial in shaping his early work - he would say that his visits to the ethnographic collections of the British Museum were more important than his academic study. Later, leading European modernists such as Picasso, Arp, Brancusi and Giacometti became influences. And uniting these inspirations was a deeply felt humanism. He returned again and again to the motifs of the mother and child, and the reclining figure, and often used abstract form to draw analogies between the human body and the landscape. Although sculpture remained his principal medium, he was also a fine draughtsman, and his images of figures sheltering on the platforms of subway stations in London during the bombing raids of World War II remain much loved. His interest in the landscape, and in nature, has encouraged the perception that he has deep roots in traditions of British art, yet his softly optimistic, redemptive view of humanity also brought him an international audience. Today, few major cities are without one of his reclining figures, reminders that the humanity can rebound from any disaster.

The foundation of Moore's approach was direct carving, something he derived not only from European modernism, but also from non-Western art. He abandoned the process of modeling (often in clay or plaster) and casting (often in bronze) that had been the basis of his art education, and instead worked on materials directly. He liked the fierce involvement direct carving brought with materials such as wood and stone. It was important, he said, that the sculptor "gets the solid shape, as it were, inside his head... he identifies himself with its center of gravity."

Related to his commitment to direct carving was a belief in the ethic of 'truth to materials.' This was the idea that the sculptor should respect the intrinsic properties of media like wood and stone, letting them show through in the finished piece. A material had its own vitality, Moore believed, "an intense life of its own," and it was his job to reveal it.

During the 1930s, Moore's most fruitful and experimental decade, he was influenced by both Constructivism and, to a much greater extent, Surrealism. From the former he came to appreciate the importance of abstract form, from the latter he derived much of his interest in lending a human and psychological dimension to his sculpture. But Surrealism also shaped his mature style. It encouraged his love of biomorphic forms, and also suggested how the human figure could be fragmented into parts and reduced to essentials.

Moore's interest in non-Western art gave much of his early work a frontal character, yet as he matured he became more interested in utilizing three dimensions. It was this which led him to introduce 'holes' into his sculptures, so that the object almost seems to grow out of an absent center.

Just as the human body inspired Moore's forms, so too did the natural world. He often derived ideas from objects such as pebbles, shells and bones, and the way he evoked them in his sculpture encouraged the viewer to look upon the natural world as one endlessly varied sculpture, created continually by natural processes. Evoking both the natural world and the human body simultaneously in his work, Moore created a picture of humanity as a powerful natural force.

Henry Moore was born in Castleford in Yorkshire, on July 30, 1898. The seventh of eight children of a mining engineer and homemaker, Moore was encouraged by his often financially struggling father to pursue higher education and a white collar career. And his father's strong opposition to the harsh physical lifestyle of mining created conflict when Moore later chose sculpting as his vocation, a job his father regarded as manual labor. Inspired by Michelangelo, Moore began modeling in clay and wood at his school in Castleford, where several of his siblings had attended and to which he had been granted a scholarship.

In 1919, after a brief period of teaching, and serving in the Civil Service Rifles regiment during World War I, Moore was awarded an ex-serviceman's grant with which he enrolled at Leeds School of Art, becoming their first sculpture student. There he met and was strongly influenced by Barbara Hepworth. Moore received a scholarship two years later to pursue studies at the Royal College of Art in London. While there he spent much time at the British Museum studying their ethnographic collections, which strongly informed his later monumental figurative works. In 1924 he toured Italy and France for six months where he was impressed by the art of Giotto, Masaccio and Michelangelo. Upon his return to Paris, he enrolled in classes that periodically met at the Louvre. And it was in Paris, at the Musée d'Ethnographie, that he encountered a plaster cast of the Chacmool, an Aztec sculpture from c.900-1000 AD that would be a crucial influence on his early work (the original sculpture is in the collection of the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico City). The Chacmool encouraged his inclination to create direct carved, single figures focused on their mass and form.

After his schooling, Moore accepted a seven year teaching position at the Royal College of Art in London. In 1928, he quickly received his first public commission, West Wind, from the London Underground. During this time he also married Kiev-born painting student Irina Radestsky, and they joined a group of enclave of artists, architects and writers - including Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Naum Gabo and Piet Mondrian - living in north London.

Moore became Head of the Department of Sculpture at the Chelsea School of Art in 1932. During this time he joined forces with Hepworth, her partner Ben Nicholson, and several other abstract modernists, to dominate the Seven and Five Society. Together they regularly visited Paris to see work by Picasso, Braque and Giacometti. Moore abandoned a brief interest in Surrealism in 1936 after his role as an organizer of the "London International Surrealist Exhibition" and returned to his modernist figurative work in 1937 with a career-changing sale of Mother and Child to a private collector whose public display of the monumental work created two years of protest and controversy in his conservative Hempstead community.

Moore was forced to resign his teaching post and accept a commission as a war artist at the onset of World War II. During this time he made a series of drawings of Londoners sheltering from bombing raids on the platforms of subway stations. He spoke of being struck by the sight of the figures - so like his own sculptures - stretched along the platforms, and rendered them almost as cocoons, or hibernating animals. In 1940, Moore's own home was bombed, so they moved to a farmhouse in Perry Green where he lived and worked for the rest of his prolific career.

In 1946, Moore traveled to America for the first time to view his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At the same time, with the birth of his daughter, Mary, and the death of his mother, his usually single-figure work transformed to reflect his new family structure, and he began to be interested in the mother and child motif. Yet his work also became more abstract. He became interested in the idea of puncturing the previously integral form of his sculptures with holes, and playing on the contrast of positive versus negative space. In 1950, he completed a multi-figured sculpture called Family Group, his first large-scale public bronze, commissioned by a secondary school in Stevenage. During the 1950s, Moore's public works were in steady demand. Prices for his pieces increased significantly and his profile as an international artist was heightened. With increasingly larger and more complicated commissions, including UNESCO's Reclining Figure, Moore added apprentices and assistants to his workshop, a move that while practical, drew criticism from some art world purists.

By the 1970s, Moore's work was included in over 40 shows a year and he was one of the most financially successful living artists in the world. At the end of that decade, the Henry Moore Foundation, which now manages his home as a gallery and museum, was founded to promote the preservation and publicity of his public works. Many honors were bestowed upon him, including receiving knighthood in 1951, the Companion of Honor in 1955, the Order of Merit in 1963; and later gained positions as a Trustee at both the National Gallery and the Tate.

During his lifetime, Moore became synonymous with modern sculpture in England, America and beyond, introducing a wide public to modern styles such as Surrealism and primitivism. Indeed he is almost synonymous with the many worldwide institutions outside which his grandest public sculptures stand, encapsulating their humanitarian mission. His reputation has declined since his death, a consequence in part of the prolific production of his later years, and in part due to a distaste for his soft, sometimes cloying humanism. Yet he undoubtedly had a great impact on the generation that followed him, inspiring figures as diverse as Eduardo Paolozzi, William Turnbull, and - because they were at one time assistants in his studio - Anthony Caro and Phillip King.

http://www.theartstory.org/artist-moore-henry.htm#biography_header

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

The Yorkshire-born sculptor Henry Moore won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London in 1921, having first studied at Leeds College of Art on an ex-serviceman’s education grant. On graduating he joined the staff of the RCA as instructor in the Sculpture School. He quickly established a reputation, alongside that of Barbara Hepworth, as Britain’s most avant garde sculptor, a position he maintained until the end of his life.

- British Modernism Whistler to WWII, 2016

As the war was not conducive to producing sculpture, Moore turned his formidable creative energy to drawing, a genre he interpreted in its widest form. As well as pencil and pen and ink, monochrome washes and watercolor, he employed a range of wax crayons, which are resistant to water based media, thus giving a rich textural quality to his work. 1942 was a particularly productive year; he produced over 100 studies of working coal miners, together with many ideas for sculpture, particularly of reclining figures, as well as a series of large-format studies such as this, in which he depicted groups of figures in stark, Kafkaesque interiors, which are redolent of prison cells or Gordon’ Craig’s most avant-garde stage sets.

- Old exhibition information from the past