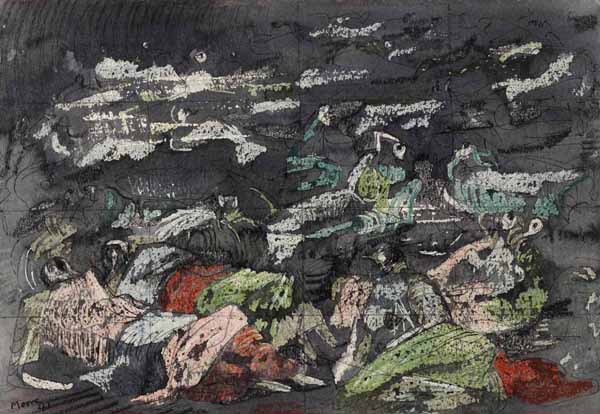

Henry Moore

British, 1898-1986

Shelter Scene, 1941

pen, ink and wax crayon on paper

6 7/8 x 9 7/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Miss Ninfa Valvo in memory of Donald Bear

1952.5

Undated photo of Henry Moore.

“The war brought out and encouraged the humanist side in one’s work” - Henry Moore

POSTSCRIPT

These drawings were exhibited for the first time in 1941. They were often interpreted as metaphors for the stoic resistance of the British people in the face of war.

COMMENTS

1940 – 1941 Shelter Drawings

When war was declared on September 3, 1939, Henry Moore was living and working at his country cottage at Kingston near Dover. For him the summers were always exceptionally productive periods when, free from his teaching responsibilities at the Chelsea School of Art, he could concentrate without interruption for several months on his sculpture and drawing.

Instead of returning to London at the end of the summer as they usually did, the Moores stayed on at their cottage for nearly a year, during the period known as the Phoney War. Life went on as before. Moore continued teaching two days a week at Chelsea, driving up to London and stopping overnight at his studio in Hampstead. In the cottage they made themselves as self-sufficient as possible. Irina Moore started a small chicken farm: Moore himself was working very hard on a number of sculptures for an exhibition to be held at the Leicester Galleries in February 1940. In December 1939 he completed the large Elmwood “Reclining Figure”, now in the Detroit Institute of Arts, as well as about a dozen small lead sculptures, including some stringed figures. As yet the war had not interfered with his work.

In June 1940, with the fall of France and an invasion of England seemingly imminent, the Phoney War came to an abrupt end. The south coast around Dover became a restricted area and the Moores knew that they would soon be forced to return to London. About this time Moore read an advertisement in a London newspaper for a Government course in precision tool-making at the Chelsea Polytechnic, which was affiliated with the Chelsea School of Art. Both he and Graham Sutherland volunteered for the course and were told they might begin at any moment. The Moores returned to their studio at Parkhill Road, Hampstead. Throughout that summer Moore waited to hear from the Polytechnic. As there was no point in starting work on a large sculpture that might have to be abandoned, he concentrated on drawing and produced some of his finest studies for sculpture.

He heard nothing further about the tool-making course; there had apparently been many more applications than places. In late August or early September, Moore took over the tenancy of a neighboring and less expensive studio at 7 Mall Studios, Tasker Road, from Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, who had moved to Cornwall with their three children. The Moores moved into the new studio before the first full-scale day and night air offensive on Saturday, September 7, 1940. Several days after the Blitz began, the Moores went to the West End of London by bus rather than taking their car as they usually did. After dining with friends they returned home on the London Underground. As the train stopped at each station, Moore, for the first time, caught fleeting glimpses of men, women and children gathered on the station platforms, making themselves as comfortable as they could for the long night ahead. Londoners had begun using the station platforms beside the tracks as air raid shelters, in spite of the efforts of the authorities to persuade them to use surface shelters.

When the Moores got off the Northern Line train at Belize Park, they were told by the air raid warden to remain below for their own safety. This may well have been the night of September 11, when General Pile had ordered the commanders of all the 199 anti-aircraft units in the London area to fire every possible round at the enemy bombers. During the first four nights of the Blitz, Anti-Aircraft Command had been relatively ineffectual because the gunners, before firing, had to identify enemy planes, in order not to hit the British fighters. On the night of the 11th, the R.A.F. night fighters were grounded so that the gunners would not be hampered.

Constantine FitzGibbon has described the effect of the anti-aircraft fire: ‘‘That night the barrage opened up, and its roar was music in the ears of the Londoners. The results astonished Pile, the London public, and apparently the German pilots too, who flew higher as the night went on”. During this barrage Moore spent about an hour on the station platform at Belize Park among the shelterers. This afforded him, he said recently, “the opportunity to observe and remain in the atmosphere of the station longer than I would have done”. His response to this experience was spontaneous and direct. Within a day or two he executed what he thinks may have been the first shelter drawings, “Women and Children in the Tube” of 1940, now appropriately in the collection of the Imperial War Museum, London.

In view of Moore's previous obsessions with the mother and child, and the reclining figure themes, it is understandable why scenes of shelter life made such an immediate and overwhelming impact. The positions of the shelterers and the setting, Moore said, 'fitted in with me perfectly'. They combined two of his favorite motifs: 'I saw hundreds of Henry Moore Reclining Figures stretched along the platforms, and even the train tunnels seemed to be like the holes in my sculpture'. The circumstances of war had put in his way a subject, which related to his previous work and with which he could identify emotionally. Sharing the dangers of living in London during the Blitz, Moore said 'I was very conscious in the shelter drawings that I was related to the people in the Underground'.

Following this first contact with shelter life, Moore began visiting various stations to study and absorb the chaotic scenes on the crowded platforms. During the first two months of the Blitz, each night an average of 100,000 people sheltered in the London Underground. On his return home, he began filling the 'First Shelter Sketchbook' with drawings done from memory, based on the subterranean world, which he has compared to 'a huge city in the bowels of the earth'.

ln November 1939 the Ministry of Information appointed Sir Kenneth Clark Chairman of the War Artists' Advisory Committee, whose purpose it was to select suitable artists to record not only the military aspects of war, but also life at home and in the factories, the activities of the Home Guard and other voluntary groups. Early on in the war, when Clark had tried to persuade Moore to become a War Artist, he had declined because he felt at the time that the war had not changed life noticeably, it had 'made no difference, no emotional impact on me'. But with the bombing of London and his encounter with shelter life, he had found inadvertently a subject that both fascinated and deeply moved him. When Clark was shown the drawings in the ' First Shelter Sketchbook', he asked Moore to reconsider, and this time he did not refuse.

Sometime in October 1940, the Moores spent a weekend near Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, with their friend Leonard Matters, a Labor Member of Parliament. There was a particularly heavy raid on London that week-end, which Moore remembers seeing from Much Hadham, some twenty-five miles north of the city. On the Monday morning the Moores returned to Hampstead to find their studio badly damaged by the blast from a bomb that had completely destroyed a neighboring studio. That night they returned to Much Hadham and stayed with Matters until they could find a house to buy or rent. At Perry Green, a small hamlet just outside Much Hadham, they were able to rent part of an old farmhouse called Hoglands. A few months after they had moved in, the entire house was offered for sale, and this just at the time when Moore had sold the large Elmwood, 'Reclining Figure' of 1939 for £300, the exact amount required for the deposit on the property. They bought the house and there they have lived to this day.

The style of the shelter drawings is pre-figured in several works of 1940. In the Tate Gallery's 'Two Seated Figures', the clothed figures and the naturalistic treatment of the subject are features, which characterize the shelter drawings as a whole. In 'Standing, Seated and Reclining Figures against a Background of Bombed Buildings', also of 1940, imaginary figures are set against a jagged and fractured background of ruined buildings. Though the reclining figures recall the studies for sculpture of the previous few years, the draped standing figure at the left anticipates the style of the shelter drawings. Groups of figures in the bombed streets of London were to be the subject of a number of sketchbook pages and of one large drawing. Most prophetic is 'Air Raid Shelter Drawing: Gash in Road' of 1940 which, the artist said, was based on bomb damage he had seen, although he invented the figures sheltering underground. The 'Eighteen War Sketches' of 1940 comprise small studies of some of the more usual iconography of war: searchlights, gun shells bursting like stars, barbed wire, bombs bursting at sea.

Moore has described 'Women and Children in the Tube' as his first shelter drawing. Though there is little that suggests the setting of the London Underground, except for the curved wall behind the bench, and the edge of the platform at bottom right, the drawing is, nevertheless, a kind of preliminary statement, incorporating motifs, which are found in many of the shelter drawings. To begin with, there is the tightly knit group of seated figures, three women, each holding a child. In nearly all Moore's previous multi-figure compositions, the ideas for sculpture appear either in quite regular rows or they are crowded together in no particular order. Each study is isolated in space from neighboring figures. In the shelter drawings, depicting the crowded conditions on the station platforms, Moore was faced with the problem of organizing multi-figure compositions of a far greater formal complexity than anything he had attempted in his earlier drawings. Another feature that occurs in many subsequent drawings is the way in which the figures in the foreground are clearly and crisply defined, while those in the background become less distinct and fade away into the distance, diagonally across the page.

We have seen how certain pre-shelter drawings look forward to the more naturalistic style of the studies of shelter life. But it is also true that some of the earliest shelter drawings, especially those at the beginning of the 'First Shelter Sketchbook', which the artist gave to Lady Clark, are a continuation of the more abstract, anti-naturalistic style of the drawings and sculptures of the late 1930’s. It must be remembered that Moore began the shelter drawings quite unexpectedly, at a time when he had been concentrating on his drawings for sculpture. As the artist said, 'I could not throw to one side all my sculptural interests and preoccupations', and yet he realized that the subject demanded a new approach. Of the shelter and coalmine drawings Moore has said: '... I think I could have found sculptural motifs only, if I'd tried to; but at the time I felt a need to accept and interpret a more "outward’’ attitude.' The transition from the style of the sculptural subjects to a more naturalist approach was thus both conscious and deliberate.

In the first dozen or so pages of the ‘First Shelter Sketchbook', both styles are very much in evidence. In Fig.44 the mother and child study at the upper left is clearly related to certain sculpture drawings of the previous four or five years. The idea was, the artist said, 'made up', and had no real connection with shelter life. The two standing figures and the half figure, on the other hand, were based on the memory of an actual scene in the London Underground, and illustrate the emergence of a more naturalistic approach to the subject.

In several early sheets in the 'First Shelter Sketch book' the sculptural style predominates. In Fig.45, the reclining figure at upper right, and the large sculptural object, are related stylistically to previous drawings for sculpture. The large form in the centre of the page is, Moore pointed out, an abstract idea for drapery from a purely sculptural point of' view. Sculptural ideas appear less frequently towards the end of the 'First Shelter Sketchbook', and, with the exception of two or three drawings, do not occur in the 'Second Shelter Sketchbook', belonging to Irina Moore.

In the first half of the 'First Shelter Sketchbook', Moore explores most of the subjects and compositions which were to comprise the shelter drawings as a whole; groups of figures sitting and reclining on station platforms, the mother and child theme, studies of individual shelterers, views straight down the train tunnels with two row of reclining figures, and people wandering about the streets amid debris on the morning after a raid. Fig-46 includes five group compositions, including what must be the first sketch of the Liverpool Street Extension, the setting for one of the most famous shelter drawings, 'Tube Shelter Perspective' in the Tate Gallery.

Moore's working method in the shelter drawings is of considerable interest. The drawings fall mid-way between the life studies based on direct observation and the drawings for sculpture done from the imagination. Moore explained the creative process involved when he said the shelter drawings were not drawn from nature but “from the memory of actuality”. After all, the shelterers were leading private or family lives, though in a communal environment. To sketch them directly would have been an intrusion on their privacy. If, however, a particular scene or group of figures held Moore's attention, he would walk past a number of times trying to flx the idea firmly in his mind. Occasionally he went into a corner or exit passage to make hurried notes on the back of an envelope or on a scrap of paper, either brief descriptions or small sketches. These served as vivid reminders when he came to recreate the scenes in the sketchbook. This was not the first time Moore had worked from memory. During his student years he occasionally made drawings at home, done from the memory of the life model he had drawn during the day at the Royal College of Art.

On his return to Hoglands, having spent one or two nights visiting various stations in the London Underground, Moore would spend several days drawing in the sketchbook, while the groupings and positions of the shelterers were still fresh in his mind. He would fill six or seven pages and from these choose one or two to be made into much larger, more finished drawings. He then returned to London for more visual material. In this way he filled the first and second Shelter Sketchbooks. Two unfinished ones were broken up and some of the sheets sold. About sixty-five finished drawings were enlarged from studies in the sketchbooks. Of these, seventeen were purchased by the War Artists' Advisory Committee, who later distributed them among museums throughout England.

Scattered throughout the sketchbooks were lists of possible subjects, a way of recording quickly the overflow of ideas and remembered scenes (this practice has a precedent in the notebooks of the 1920’s and 30’s, in which Moore often made lists of subjects for drawings). One such note describes a scene looking out from a shelter, a reminder of the destruction above: 'View from inside shelter at night time, with moonlight and flare light on bombed buildings'. Another inscription emphasizes the importance of memory in the shelter drawings: 'Remember figures seen last Wednesday night (Piccadilly Tube). Two sleeping figures (seen from above) sharing cream colored thin blankets (drapery closely stuck to form). Hands and arms. Try positions oneself'. More than any other note in the sketchbooks, the last sentence reveals Moore's determination to base the drawings on life. It was as if he himself wanted to experience something of the tension and exhaustion expressed in the poses seen.

London Underground stations all look very much the same and Moore made little attempt to differentiate between them. Once he had sketched the general setting, which in most of the drawings meant a station plat form with a curved wall and sometimes a tunnel in the distance, he concentrated on the groups and positions of the shelterers. Several shelters, however, differed from the rest and these particularly attracted his attention. One was at Tilbury in the basement of a large warehouse. 'A Tilbury Shelter Scene' (No.149) in the Tate Gallery, shows the enormous size of this shelter, with bales of paper at upper right. For Moore the most visually exciting of all was the newly built and still unfinished tunnel of the Liverpool Street Extension, with, in his own words; 'no lines [the tracks had not been laid], just a hole, no platform, and the tremendous perspective'. When he first saw it, the tunnel floor was occupied by two regular rows of sleeping figures, with a narrow aisle between them. The first sketch of this shelter, which appears near the beginning of the 'First Shelter Sketchbook', (Fig.46), almost certainly dates from late 1940. Seven other sketches and larger drawings are known, culminating in the definitive version of this subject, 'Tube Shelter Perspective' in the Tate Gallery (No.160). A dim grey-blue light pervades the scene. This bleak, cave-like setting shows little evidence that the tunnel is in fact part of the London Underground system. Two rows of sleepers lying on their backs recede deeply into the picture space. The seven or eight figures nearest us in each row are carefully worked; the rest gradually become mere shadows of the human form, and fade away into the distance; The spiraling tunnel suggests the eye of a tornado, a place of silence and yet of terrifying tension. It is as if we are looking into a sculpture, deep in a Moore cavern, inhabited by a race invented by him. The subterranean setting· is timeless and anonymous; it is as if we have come unexpectedly upon the tomb of a mass burial. The bodies, swathed like Egyptian mummies, seem to belong more to the dead than the living. A passive yet terrifying scene, this drawing is one of the most memorable images of civilian life produced by an artist during the Second World War.

During his initial contact with the shelterers, Moore was attracted by the spontaneous and somewhat disorganized character of shelter life. One inscription in a sketchbook records: 'Muck and rubbish and chaotic untidiness around'. This atmosphere is apparent in a number of the earliest shelter drawings, those of late 1940. In one of the most beautiful, titled 'Shadowy Shelter' in the Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, reclining figures, and several seated figures at the extreme right, sprawl diagonally across the page. Several bodies share a single blanket and are joined by the strokes of wax crayon and pen and ink lines, which define the drapery. The figure in the central foreground could almost be a preparatory study for the Time Life: 'Draped Reclining Figure' of 1952-3 (Fig.47). A discussion of the influence of the shelter drawings on Moore's subsequent sculptures appears at the end of this chapter.

Most of the drawings depict either crowded station platforms or two or three figures, but occasionally there is a single shelterer. In drawings such as the 'Shadowy Shelter' just discussed, anonymous human beings huddle together, and little attention is given to individual facial features. In other drawings, usually of one or two figures, Moore concentrates on what he has called 'the psychological, human element'. The dominant mood he was trying to convey was the sense of drama and expectancy, 'the feeling of people being underground with the knowledge of something happening above'. In 'Air Raid Shelter: Two Women' in the Leeds City Art Galleries (No.143) the two draped seated figures have the monumental grandeur which Moore so admired in the work of Masaccio. They sit and wait; the train tunnel recedes into the distance behind them. The tragic nobility of their faces suggests a passive acceptance of a fate over which they have no control. Perhaps, like the anxious woman in 'The Dry Salvages', from T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, they will remain awake through the long night:

Trying to unweave, unwind, unravel

And piece together the past and the future,

Between midnight and dawn, when the past is all deception,

The future futureless, before the morning watch

When time stops and time is never ending.

Scenes from the bombed wreckages of London's streets and buildings were the only other war subject that attracted Moore. Although he found them ‘terribly dramatic and exciting', street scenes were not as humanly touching a subject as shelter life. In 'Morning after the Blitz' of 1940 (No.145) people wander about amid the rubble, with the stark wires of the tram lines hanging precariously overhead. Such was the devastation, which the shelterers often saw, in the early morning when they emerged from the ·· Underground station platforms. In “Little Gidding”, another of Eliot's Four Quartets, he describes a similar if less crowded scene, in which the poet walks the streets of London after an air raid:

In the uncertain hour before the morning

Near the ending of interminable night

At the recurrent end of the unending

After the dark dove with the flickering tongue

Had passed below the horizon of his homing

While the dead leaves still rattled on like tin

Over the asphalt where no other sound was.

'Group of Shelterers During an Air Raid' of 1941, in the Art Gallery of Ontario (No.151) was closely based, as it would appear were all the large drawings, on a sketchbook study. Page 17 from 'Second Shelter Sketchbook' squared for transfer, is reproduced here (Fig. 48) to show how closely the original sketch was followed. The squared pencil lines are faintly visible in the Toronto drawing. Ideas related to earlier drawings and sculpture do surface in a few sheets in the 'Second Shelter Sketchbook', as in the two reclining figures at the top of p. 17. Although Moore did not choose to enlarge any of the purely sculptural ideas that appear in the sketchbooks, some of the figures do combine both naturalistic and more abstract forms. An example of the latter is the thin axe-like head of the figure at the right in the Toronto drawing, which anticipates the head of the bronze 'Warrior with Shield' of 1953-4 (L.H.J60, Fig.24).

Drapery was an extremely important new element in the shelter drawings and one, which was to have far reaching implications for Moore's subsequent drawings and sculpture. Though draped- figures do appear in a number of earlier sculptures arid drawings (see Nos. 122 and 135), it was not until he began the shelter drawings that Moore made a serious study of the subject. He has said, in fact, that drapery was the one formal element with which he was not entirely familiar.

The use of drapery in the shelter drawings was of course in response to the subject itself: fully clothed figures often wrapped or covered with blankets, shawls and bed-clothes that served as protection against the draughts in the London Underground. Reference has already been made to a study of drapery from an abstract, sculptural point of view on p.10 of the 'First Shelter Sketchbook' (Fig-45). In studies of fifteen or twenty shelterers the drapery, though very much in evidence, is not given special emphasis. But in some of the drawings of three or four figures, the drapery almost becomes the subject itself, exiting as an independent form. On page 6 in the “Second Shelter Sketchbook” is written, “bundles of old clothes that are people”.

The importance of drapery is well illustrated in 'Air Raid Shelter: Two Mothers Holding Children' of 1941 (Fig.49). The drapery creates an external shell protecting the internal forms within. In the study at left, the passage depicting the heads of the mother and child, and the marvelous rhythm of the edge of the blanket curving around the forms, is one of the most beautiful in all the shelter drawings. Thematically the internal and external forms created by the drapery around the figures look forward to several important post-war drawings and sculpture, most notably in 'Ideas for Sculpture: Internal and External Forms' of 1948 (No.217), and in two bronzes- 'Internal and External Forms' of 1953-4 (L.H.297, Fig.26) and 'Reclining Mother and Child' of 1960-r (L.H.48o).

In the life studies of the early 1920s, Moore often combined as many as four different media in a single drawing: pencil, chalk, pen and ink and wash. Some time before the war; while doing some drawings to amuse his niece, he discovered quite by accident another medium, wax crayon, and this was used extensively in the shelter drawings and coal-mine drawings which followed. The artist has explained the technique and the use he made of the medium:

I used some of the cheap wax crayons (which she had brought from Woolworth's) in combination with a wash of watercolor, and found, of course, that the watercolor did not 'take' on the wax, but only on the background.

I found also that if you use a light-colored or even a white wax crayon, then a dark depth of background can easily be produced by painting with dark watercolor over the whole sheet of paper. Afterwards you can draw with India ink to give more definition to the forms. If the waxed surface is too greasy for the India ink to register it can be scraped down with a knife.

The extraordinary surface richness and sense of depth in many of the shelter and coal-mine drawings are thus achieved with as many as five media: pencil, chalk, wax crayon, pen and ink and watercolor.

Because the vision behind Moore's drawings is that of a sculptor, interested primarily in showing the three-dimensional shape of things, color is of secondary importance. Moore states in an unpublished note on drawing that he uses 'color for its emotional effect, not its decorative or realistic effect'. In the shelter drawings, working as he did from memory, the colors were freely invented, rather than precise descriptions of what he had seen. Occasionally the dominant colors are included in the title, as in 'Pink and Green Sleepers' in the Tate Gallery. Perhaps more important than details, such as brightly colored blankets found in a number of shelter drawings, is the emotional effect and atmosphere achieved by the overall tonality. The blue-grey tonality in the Tate Gallery's ‘Tube Shelter Perspective' (No.160) emphasizes the dim eerie light of the tunnel.

Among the most powerful and disturbing of the shelter drawings is the series of sleeping figures seen from a low viewpoint, as if we were kneeling at their feet (Nos.162-8). Only the arms and foreshortened heads are visible; the rest of their bodies are covered with blankets. Four studies related to the series are unique among Moore's drawings in their almost expressionistic violence and frenzied execution (see No. 162). Two preparatory studies for one of Moore's most famous drawings, the Tate Gallery's 'Pink and Green Sleepers', are included in the exhibition (Nos. 163 and 164). Dr Walter Hussey's 'Two Sleepers' (No. 167) is surely one of the most haunting and terrifying drawings Moore has ever produced. The focus on the two heads is even closer than in the Tate version of a similar subject. The mouths hang open; the eyes, hardly visible, do not belong to the living. The hand of the figure at right is like a claw without flesh. A blanket is drawn up under the chins of the two figures. Above, is as if someone has gently pulled back the other blanket and uncovered the faces of the dead.

The shelter drawings mark a turning point in Moore's development. His dedication, experience and love of drawing in the 1920s and 30s had made the shelter drawings possible: 'If I had not been interested in drawing, and spent fifteen years doing life drawing, and put so much time and effort into my drawings for sculpture up to the war, I couldn't possibly have done the shelter drawings', Before the war, drawing had been, Moore said, 'a second string in one's bow', although of ‘vital importance to his development as a sculptor. But the war temporarily diverted his attention away from sculpture and for nearly two years he worked exclusively on drawing. Dealing with a subject from life, which profoundly moved him, the humanist side of his nature, which for so long had been in conflict with his interest in primitive art, found an outlet in the shelter drawings. In 1946 he wrote to James Johnson Sweeney: And here, curiously enough, is where, in looking back, my Italian trip [1925] and the Mediterranean tradition came once more to the surface. There was no discarding of those other interests in archaic art and the art of primitive peoples; but rather a clearer tension between this approach and the humanist emphasis. He was to see shelter and coal-mine drawings as 'perhaps a temporary resolution of that conflict which caused me those miserable first six months after I had left Masaccio behind in Florence and had once again come within the attraction of the archaic and primitive sculptures of the British Museum'.

In the same letter to Sweeney, Moore also said:

You will perhaps remember my writing you in 1943 that I didn’t think that either my shelter or coal-mine drawings would have a very direct or obvious influence on my sculpture when I would get back to it except, for instance, I might do sculpture using drapery, or perhaps do groups of two or three figures instead of one. As a matter of fact the Madonna and Child for Northampton and the later Family Groups actually have embodied these features.

Mention should also he made of ‘Three Standing Figures' of 1948 (L.H.268), now in Battersea Park, London, which is related to what Moore has called one of the pervading themes of the shelter drawings: ‘the group sense of communion in apprehension'.

Not only did the shelter drawings have a tremendous influence on Moore's subsequent work, but they also made a considerable difference to his relationship with the general public. The War Artists' Advisory Committee organized exhibitions at the National Gallery, which were among the few to be seen in London during the war. Here thousands of people saw Moore's shelter drawings for the first time. They acquainted a large public with his ability to render the human figure in a disarmingly straightforward and profoundly moving way. And the subject, the Londoners themselves, was one with which his audience could readily identify. From the sales of the shelter drawings to the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, Moore found that he could support himself without recourse to part-time teaching.

The shelter drawings record what Moore has described as 'an extraordinary and fascinating and unique moment in history. There’d been air raids in the other war, I know, but the only thing at all like those shelters that I could think of was the hold of a slave-ship on its way from Africa to America, full of hundreds and hundreds of people who were having things done to them that they were quite powerless to resist'. The influence of his wartime experiences was not limited to his work alone: ‘Without the war, which directed one’s direction to life itself, I think I would have been a far less sensitive and responsible person if I had ignored all that and went on working just as before. The war brought out and encouraged the humanist side in one's work.'

The shelter drawings may be described as visionary, not in the religious sense of the word, but in the interpretation of a deeply felt, highly imaginative experience. As such they go far beyond the kind of factual, documentary record of war produced by many war artists. In their almost visionary intensity, Moore's shelter drawings have, with Samuel Palmer's watercolors of his Shoreham Period, a rightful place among the supreme achievements of English graphic art.

Excerpted from Henry Moore, Wartime Drawings, 1940 -1944

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In 1940 Moore was appointed an Official War Artist, in which capacity he served until 1942, making records of coal miners at work in his native Yorkshire, and drawing the crowds of people who took refuge in London’s Underground Stations, where they slept each night during the Blitz.

British Modernism form Whistler to WWII

2016

This drawing is part of the oeuvre of the period 1940-1943 while Moore, as an official war artist was making his “shelter” drawings depicting life during the bombing of Great Britain during World War II. Residents of such large cities as London literally went underground during these years, living and sleeping in basements and subway tunnels during the air raids, which devastated the cities above them. One result was relatively little loss of life during the destruction of the cities; another was firming of the already resolute will of the British to resist. The earlier of the two drawings clearly represents figures lying down for the night’s sleep; with Moore’s characteristically impersonal style, they take on a universal symbolism. The later drawing, although possibly simply a study of figure masses in architectural space, seems also related to the shelter series, with some suggestion of alienation of the figures from each other, and hints of mystery and even ominous expectation.

SBMA label from past exhibition