Adolphe Monticelli

French, 1824-1886

Park Scene, 1875-78

oil on wood panel

16 3/8 × 26 1/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. John D. Graham in memory of Buell Hammett

1948.28.1

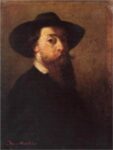

Adolphe Monticelli, Self-Portrait, n.d.

"Monticelli sometimes made a bunch of flowers as an excuse for gathering together in a single panel the whole range of his richest and most perfectly balanced tones... you must go straight to Delacroix to find anything equal to his orchestration of tones.”

- Letter to Theo, 25 March 1888

COMMENTS

He was Paul Cezanne's companion and Vincent van Gogh's idol, and his odd, encrusted pictures - unlikely as it sounds - link the thickly brushed abstractions of New York action painting with the flirtatious and courtly fantasies of 18th century France.

Adolphe Monticelli (1824-1886) was a most peculiar painter and a most peculiar man. He claimed he could see souls (they looked like colored flames), often spoke with God, and said he had known Titian in a previous existence.

Those who think art history should be linear and logical trip on Monticelli. He jumps out of their cubbyholes. How could one man influence painters as diverse as van Gogh, Chaim Soutine and Albert Pinkham Ryder? Where does one place pictures that are, like Monticelli's, both avant garde and old-fashioned? …

Most textbooks treat the period as a time of battle. On one side are the good guys - Manet, Cezanne, van Gogh - who led art toward abstraction while their dull opponents, oblivious to progress, rehearsed stagnant themes. But Adolphe Monticelli fought on both sides at once.

His wild, patterned brush strokes, unearthly colors and avoidance of sharp focus please friends of the modern who prefer to ignore the scenes he chose to paint. In fact, there is nothing at all new about the knights, nymphs and dryads who flirt with one another in Monticelli's dappled glades. His garden scenes are as sweetly scented as the rococo romances painted by Watteau.

These densely painted pictures, so daring in technique, cast light on the terra cotta lovelies sculpted by Rodin and on the naked bathers painted by Cezanne. How could men so modern address themes so antique? The Monticellis here suggest at least one answer: the conflict between old and new is more of our age than of theirs.

"I am painting for 50 years in the future. It will take that long for people to see my painting," said Monticelli, yet in almost every picture he celebrates the pleasures of an imaginary past.

He was a good friend of Cezanne's. The two men would spend weeks with their easels and their sketchbooks, wandering the country roads of their native Provence. Van Gogh never met him, but he collected Monticellis and, following his idol, set out in his last years for the South of France.

"I owe everything to Monticelli, who taught me the chromatics of color," wrote van Gogh. "He was a strong man - a little cracked, or rather very much so - dreaming of the sun and of love and gaiety . . . a thoroughbred man of a rare race, continuing the best traditions of the past . . . Now listen: for myself I am sure that I am continuing his work here, as if I were his son or his brother."

- Paul Richard, Monticelli's Wild Vision, The Washington Post, April 29, 1979

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1979/04/25/monticellis-wild-vision

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Courtly scenes like these bear no resemblance to anything produced by better known artists in the generation of Monticelli, which was dominated by Courbet’s Realism with its populist message of art of the people, for the people (meaning the bourgeoisie and working class). Monticelli was attracted to the precedent set by the Rococo master Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), who defied Italianate classicism by looking to the 17th-century Flemish colorist Peter Paul Rubens for inspiration in his dream-like masterpiece, Voyage to the Island of Cythera. Van Gogh’s admiration for Monticelli’s artistic independence resembles the esteem in which he held his earlier artist heroes, Millet and Michel, even though Monticelli’s art is diametrically opposed to their versions of Naturalism.

The 19th-century Rococo Revival comprised not only the Realist strain of Chardin. It also included artists like Watteau and his follower Nicolas Lancret, who further propagated this gentle and often blatantly unreal vision of the courtly elegance of a bygone era. Certainly, for Monticelli, the widespread revival of interest in these 18th-century painters provided an endless well of inspiration for his own art.

- Through Vincent's Eyes, 2022