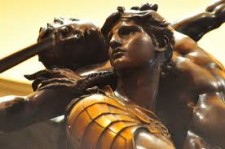

Antonin Mercié

French, 1845-1916

Gloria Victis, 1874 after

bronze with gilding

36 1/2 x 21 1/8 x 15 1/4 in.

SBMA, Museum Purchase, 19th Century Art Acquisition Fund

1998.28

Mercié at his easel, drawing by Ramon Casas

RESEARCH PAPER

Marius Antonin Mercie’s Gloria Victis provides us with an opportunity to contemplate the importance of l9th century French sculpture from both the aesthetic and historical viewpoint. French sculpture provides us with insights into American sculpture as well, because the l9th century was a period of enormous influence on the youthful United States. Many American sculptors chose to study in Rome and Paris, such as the great American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens who was a classmate of Mercie at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. French and Italian sculpture was interesting to Americans not only because of its quality, but because of the same quest for images which would provide inspiration and arouse the nationalistic spirit. In France, sculpture’s public role was clearly defined. It was to represent the most noble thoughts and deeds of mankind.

Political and economic factors influenced monumental sculpture during the l9th century in France. Many royal monuments had been demolished following the Revolution, especially those glorifying the authority of an individual. Having begun with a nearly clean slate sculpturally, l9th century citizens disparaged the use of public monuments to glorify a single individual’s power. The rise of nationalism required monuments that would summarize public opinion and satisfy the working and middle classes. (Hargrove, p. 21.) Industrialization had also brought about an increasing association of sculpture with architecture. A period began during which most monumental art represented distinguished individuals who provided role models for the masses to emulate. The changes of the l9th century affected sculpture even more than painting, due to technological advances that aided production, and sculptors no longer had to depend only on commissions from the church and state. A great quantity of French sculpture of the later l9th century exists, some of which was created to satisfy the demands for art by the wealthy bourgeoisie. Nevertheless, although the church and State were no longer the sole sources of commissions, the expense of producing bronze and marble sculpture was prohibitive for the majority of artists. Few could afford the up-front cash outlay needed to have their works produced. Consequently, many, if not most, still had to have the patronage of the academy or the State in order to survive. Because of this, an artist could not afford to take risks, and his subject matter was more or less dictated by the conservative, traditional tastes of the French academy and State. Another factor in the perseverance of the conservative style was the enduring academic concept of sculpture as “the image of eternity” which formed the basis for l9th century sculptural tradition (Boime p. 14), of which Mercie was very much a part.

Marius Mercie was born in Toulouse, France on Oct. 30, l845. His early life, and indeed his adult career, is one of academic and artistic successes. He attended the prestigious and conservative Ecole des Beaux Arts, where he studied under Jouffroy and Falguierre. While a student there, his l868 sculpture of Theseus and the Minotaur won the Grand Prize. Beginning his long public career with a portrait medallion of a young girl which won accolades, for the next forty-six years this prolific and gifted sculptor literally covered France with his monuments. In understanding Mercie’s work, it is important to realize that this extremely gifted artist was one of those whose work conformed to the French academy’s standards of artistry and whose work they praised and awarded lavishly. While this does not in any way diminish the daring and brilliance of artists who broke with the styles and standards of the academy, it also does not diminish Mercie’s talent. Mercie enjoyed uncommon success. His models for David and Gloria Victis, which he executed in Rome in 1869 and 1873, were critically acclaimed at the Salons of l872 and l874. While still a student at the French Academy in Rome, Mercie was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor, an award never before given to an artist who was still a student. The influence of Donatello, which is obvious in Mercie’s David, was part of a renewed interest in the 19th century in Florentine Renaissance sculpture. Allegorical themes were also very popular, particularly those which represented noble concepts, such as the Gloria Victis. (Fusco.) The Gloria Victis was originally exhibited as a life-size plaster model in 1873, and was purchased by the city of Paris for 12,000 Francs and later bronzed. It is truly a magnificent example of 19th century French monumental public art.

Mercie worked tirelessly all his life to maintain the exalted reputation which he had earned and the fame which he had achieved before his 30th birthday. For this he was considered one of the “leading lights” of French sculpture. Mercie also began painting in l880, and his work in that medium also won accolades from the Salon, winning medals in 1883 and 1889. His sculpture won highest awards at the Exposition Universelles of 1878 and 1889. Mercie was elected in 1889 to the Institute de France, a success he followed in 1890 by becoming a professor at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and was then promoted to the rank of Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. In 1913, he capped his achievements with election as president of the Societe des Artists Francais.

The Gloria Victis provided the French with much-needed solace following their devastating loss of the Franco-Prussian War. In 1870, while Mercie was still a student at the French Academy in Rome, the Prussians invaded France. Originally, Mercie sculpted a figure of Fame, or Winged Victory, carrying in glory a victorious soldier. Following the French army surrender, Mercie changed the figure of the exultant soldier to that of a defeated one - a broken sword still clutched in his hand. The title of the work, Gloria Victis, literally means “Glory to the Vanquished”, and was coined as a rejoinder to the ancient motto “Vae Victis” (Woe to the Vanquished). This patriotic message was no doubt a part in the overwhelming outpouring of public praise for this work. The bitterly defeated French found comfort in this portrayal of heroism in defeat. The story surrounding its creation elicited powerful responses from an anguished nation. The young man portrayed in the work was a personal friend of Mercie’s and a fellow artist by the name of Henri Regnault. The patriotic Regnault was killed on the last day of the Franco-Prussian war while taking part in the defense of Paris. His body lay unidentified for several days. The tragic death of their beloved colleague and friend inspired many artists to remember him in their work. But it was Mercie’s Gloria Victis that stood out among all the others and won the highest praise. (Shepherd Gallery Associates, Spring l985 Exhibition Catalog.)

Patriotic reasons aside, the work is of considerable artistic interest. At the time, it was considered to be daring compositionally. During the 1860s, several Salon sculptures addressed the formal problems of representing a figure balanced on one foot. The Gloria Victis demonstrates one-footed support for two figures. Because of this compositional element, Gloria Victis influenced numerous works including Rodin’s Call to Arms. (Fusco.) Mercie’s inspiration for the Gloria Victis was the Nike of Samothrace which had been discovered on the Aegean Island of Samothrace in 1863 and sent immediately to the Louvre in Paris. The eight foot tall marble figure, created by a Rhodian sculptor between 220 and 190 B.C. is considered to be the finest extant Hellenistic Greek sculpture. The statue’s head and arms are missing. (Note: to this day, Samothracians would like to have this statue returned to its native soil.)

The bronze statue, a reduction of the life size original, stands 36 1/4 inches tall, with a coppery, medium and dark brown patina. On the self-base at the right is the signature of the artist, incised after casting: A. Mercie. On the front rim of the base, the title of the piece is incised after casting: Gloria Victis. The foundry mark, F. Barbedienne, Foundeur, is located on the upper right rim of the base. The piece is wonderfully expressive, with an overall uplifting feeling - almost as if it were airborne. The Winged Victory carries the wounded youth in her arms, tenderly embracing his thighs as she supports his weight with her body. At Victory’s foot are a laurel branch (Victory’s customary crown) and an owl (the symbol of wisdom.) The meaning of the placement of these items remains unclear, and the artist’s intent is not explained by any reference to them. They could be interpreted literally, they could have meant something personal to the artist, or they could reflect a literary reference well known at the time. The detail of the work is very intricate, each item delicately realized; the hands, the feet, the breastplate on the Winged Victory. Both of the figures are extremely handsome and have neoclassical features reflecting an idealized beauty. Because of the depth and beauty of the patina, the piece reflects light brilliantly.

Although Mercie created numerous works on commission of portrait busts, commemorative monuments and tombs, work which he continued throughout his life to international acclaim (his monument to Lord Byron stands in the Zappein Gardens, Athens), there has been little study of his works. When one looks at the vast body of French sculpture which exists, one can see why an artist such as Mercie, brilliant though he was, is not singled out for study. Along with many of the other academic artists, Mercie has been eclipsed by the adventurous sculptors with whom we are familiar, such as Rodin. Nevertheless, his life was one of enormous achievement and this was his distinguishing work. An American visitor to Paris wrote shortly after seeing the piece a few years after its first exhibition: “No effort of French genius since Sedan - no poem, romance, oration, or work of art - has given so much solace to the defeated nation as this statue.” (Shepherd Gallery Associates – Spring 1985).

The original Gloria Victis is preserved at the Musee du Petit Palais in Paris.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Patricia L. Andersons

Bibliography

Boime, Albert. Hollow Icons: the Politics of Sculpture in l9th -Century France. Kent State University Press, l987.

Cleveland Museum of Art Exhibition, “Aspects of l9th Century Sculpture”, December 10, 1975 - February 1, 1976.

Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs, vol. 7, 1976. Librairie Grund.

Encyclopedia Brittanica Online, www-eb-com, “Salon des Independants”.

Hargrove, June E. “Public Monuments”. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “The Romantics to Rodin”, French 19th Century Sculpture from North American Collections. Organized and edited by Peter Fusco and H.W. Janson. Copyright 1980.

Fusco, Peter. “Marius Antonin Mercie”. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “The Romantics to Rodin”.

Shepherd Gallery Associates, Inc. “Nineteenth Century French and Western European Sculpture in Bronze and Other Media.” Spring Exhibition 1985.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

An angel of victory has snatched the body of a moribund warrior who holds a broken sword in his right hand. Balancing on the toes of her left foot, looking over her right shoulder, wings widespread , with robe and hair billowing in the wind, the angel is about to lift off with her precious cargo. “Glory to the Vanquished!” reads this work’s title in English, a sentiment purposefully made in response to France’s defeat by the Prussian army in 1871.

- Sculptures that Tell Stories, 2019