John McLaughlin

American, 1898-1976

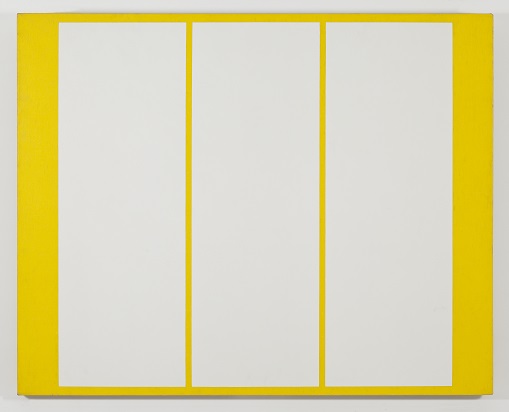

#12, 1965

oil on canvas

48 x 60 in.

SBMA, Gift of June Harwood in Memory of Jules Langsner

1978.28.2

Portrait: John Mclaughlin, 1959 Apr./ Unidentified photographer. John McLaughlin papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

“These are not meant to be ‘powerful’ pictures nor do they represent ‘objects’ nor ‘ideas’ any more than they are exercises in design made up as pleasing harmonies in endless combinations.” - John McLaughlin (Wilder, p. 6)

RESEARCH PAPER

On first looking at John McLaughlin’s geometric, hard-edge painting “#12, 1965”—or, indeed, almost any one of his paintings—we are initially tempted to see it as an art school exercise in abstract composition using a single color, a unique, repeated shape, and no obvious narrative. We may see the conundrum of figure-ground relationship, but most will observe three vertical, white rectangles over a ground of intense yellow. There are neither diagonal lines to imply motion nor curved lines to give flow or to suggest symbols. The sharp verticals on a horizontal plane present a solid, impassive, inert image which invites us, almost challenges us to make something of it.

How do we analyze a painting in which there seems to be nothing there? We see no references, neither spatial nor emotional, but we are still drawn to the painting. Fortunately, McLaughlin has provided numerous letters and interviews in which he discussed what his intentions were in painting his canvases. He addressed how he would like us to see and react to his work:

“The response that I would hope a viewer would get – and this is a very critical thing – is that he is supposed to respond to the wonder of the omission of an object. When you look at a painting with an object in it you assess it by its value as an object. So I take the object out and you’re in a position to worry about yourself, not whether this artist was a good one or is telling you anything worthwhile.…But there’s a feeling in some of these forms, in all of them I guess in a way – in that sense – they would correspond to what has eventually been known as synergy. As you know, the relatedness of everything – everything in nature is related to itself” (McLaughlin in Karlstrom interview, p. 22).

McLaughlin was, indeed, trying to create an image devoid of those elements by which we traditionally analyze a work of art. He sought a neutrality of form, color, and composition so that his paintings left the viewer with nothing but himself to contemplate and ultimately consider his place in nature, nature as the interdependence of all phenomena, both mental and physical, as expressed by the basic Zen Buddhist dichotomy “Form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.” Markus Brüderlin, Director of the Kunstmuseum Wolfburg, addressed this approach in his remarkable exhibition “Japan and the West” in 2007: “The rational emptying process, which one could also characterize as the deletion of all expression and meaning, ultimately reveals…a mystic experience. This process could provide the opportunity to allow the void of emptiness to lead in a spiritual observation” (Brüderlin, p. 226).

McLaughlin had a lifetime love of Asian art, having spent many days at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston while growing up, and he credited this art as “the motivating instrument that caused me to paint as I am painting today” (McLaughlin in Karlstrom interview, p. 1). He had long been drawn to the art of the 15th century Japanese landscape painter Sesshu Toyo (1420-1506), who was known for the large blank areas in his work which are referred to as the “marvelous void,” a “large interval between objects which is often of much greater significance than the objects themselves and can induce a state of contemplation” (Selz, p. 65).

He also was influenced by the work of Kazimir Malevich (Russian, 1879-1935), particularly his “white on white” paintings which gave the “feeling of the absence of an object,” and by Piet Mondrian (Dutch, 1872-1944) “because he was conscious of the vast significance of the neutral form” (McLaughlin in Young, p. 72). Mondrian also suggested a way of creating a totally abstract painting using neutral forms and destroying volume and plane (Larsen, p. 17).

John McLaughlin was 52 years old before he began painting full-time. In his early years he worked as a Navy seaman on a cargo ship during World War I, sold real estate in Chicago, spent two years with his wife in Japan studying the language and culture, subsequently selling Japanese prints and other works of art in their Boston gallery, The Tokaido, Inc. In World War II he was recruited by the Marines and stationed as a language officer at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, but later was deemed of limited combat value and asked to resign. He spent the rest of the war as an Army intelligence officer in China, Burma, and India. He and his wife settled in Dana Point in the Laguna Beach area of Southern California, where he devoted himself exclusively to his art.

His earliest paintings were landscapes, but he was soon drawn to the non-objective, and, he said, “The more I worked the more I took out of them” (McLaughlin in Karlstrom interview, p. 18). Encouraged by his knowledge of Sesshu, Malevich, and Mondrian, McLaughlin began developing a concept using only rectangles, which he considered the most neutral shape, oriented vertically or horizontally with the painting’s edges. His compositions were intentionally non-representational, and his colors were non-associative (e.g., the intense yellow in “#12, 1965” which does not remind the viewer of anything specific). His goal was to create empty pictures with no discernable image, no recognizable symbol, no object. “We cannot make associations or find symbols or confuse recognition with understanding. We are, in short, trapped into contemplation and participation” (Nordland, p. 50). In the Karlstrom interview McLaughlin recognized that many viewers would not understand his philosophical concepts (“I don’t think that many would get it at all,” p. 32), yet he nevertheless believed the viewer played a crucial role in his aesthetics.

“My paintings during the early fifties reflected my growing concern with the ascetic approach. This position accommodated my conviction that the viewer become central to the neutrality of the non-expressive structure. Thus, the absence of perceptible entity becomes the function of the viewer as opposed to the work itself. This is to say, his unmixed thought is content” (McLaughlin in Emmerich (1979), p. [6]).

Thus, John McLaughlin’s paintings embody a nothingness, or void, which forces the viewer into contemplation and the Zen concept of “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form” as he enters a state of metaphysical introspection. McLaughlin created paintings which are conduits to meditation without being objects of meditation.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Ralph Wilson, 2014.

Bibliography

Books

Ashton, Dore. “American Art Since 1945.” New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Karlstrom, Paul J., ed. “On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900-1950.” Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

Milner, John. “Mondrian.” New York: Abbeville Press, 1992.

Catalogs

André Emmerich Gallery. “John McLaughlin: Paintings 1949-1975,” exhibition catalogue. New York: André Emmerich Gallery, 1979.

———. “John McLaughlin: Paintings of the Fifties,” exhibition catalogue. Introduction by Prudence Carlson. New York: André Emmerich Gallery, 1987.

———. “John McLaughlin: Paintings of the Sixties,” exhibition catalogue. Introduction by Prudence Carlson. New York: André Emmerich Gallery, 1987.

Felix Landau Gallery. “John McLaughlin,” exhibition catalogue. Los Angeles: Felix Landau Gallery, 1962.

Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. “Japan and the West. The Filled Void,” exhibition catalogue. With Texts by Stephen Addiss et al. Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2007. Particularly useful essays are listed in the following section.

Laguna Art Museum. “John McLaughlin: Western Modernism/Eastern Thought,” exhibition catalogue. Essays by Susan C. Larsen and Peter Selz with an appreciation by Edward Albee. Laguna Beach, California: Laguna Art Museum, 1996.

Los Angeles County Museum. “Four Abstract Classicists,” exhibition catalogue. Essay by Jules Langsner. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum, 1959.

Nicholas Wilder Gallery. “John McLaughlin: Late Works,” exhibition catalogue. Los Angeles: Nicholas Wilder Gallery, 1979. Mostly insightful excerpts from McLaughlin’s letters.

Plous, Phyllis and Frances Colpitt. “Abstract Options,” exhibition catalogue. Santa Barbara, California: University Art Museum, 1989.

Santa Barbara Museum of Art. “Pasadena to Santa Barbara: A Selected History of Art in Southern California, 1951-1969,” exhibition catalogue. Essays by Julie Joyce, Leah Lehmbeck, and Peter Plagens. Santa Barbara, California: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2012.

Essays

Addiss, Stephen. “Minimalism and Zen.” In “Japan and the West. The Filled Void,” 277-284. Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2007.

Anderson, Susan M. “Journey into the Sun: California Artists and Surrealism.” In “On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900-1950,” edited by Paul J. Karlstrom, 180-209. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

Brüderlin, Markus. “Foreword.” In “Japan and the West. The Filled Void,” 9-14. Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2007.

———. “The Filled Void and Modern Minimalism. Japan and the West.” In “Japan and the West. The Filled Void,” 221-234. Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2007.

Colpitt, Frances. “Abstraction at Eighty: Theory and Experience of Painting.” In “Abstract Options,” by Phyllis Plous and Frances Colpitt, 11-20. Santa Barbara, California: University Art Museum, 1989.

Kawamura, Kazuhisa. “On the Design of the Japanese Garden.” In “Japan and the West. The Filled Void,” 205-206. Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2007.

Landauer, Susan. “Painting under the Shadow: California Modernism and the Second World War.” In “On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900-1950,” edited by Paul J. Karlstrom, 40-67. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996.

Larsen, Susan C. “John McLaughlin: A Rare Sensibility.” In “John McLaughlin: Western Modernism/Eastern Thought,” 15-29. Laguna Beach, California: Laguna Art Museum, 1996.

Lütgens, Annelie. “Spirit – Image – Sound.” In “Japan and the West. The Filled Void,” 235-246. Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2007.

Selz, Peter. “Abstract Classicism Reexamined.” In “John McLaughlin: Western Modernism/Eastern Thought,” 63-67. Laguna Beach, California: Laguna Art Museum, 1996.

Periodicals

Cotter, Holland. “What the Wyeth Crowds Don’t Stop to See.” New York Times, December 15, 1996, n. pag. Review of Laguna Art Museum exhibition in Baltimore Museum of Art.

———. “Art in Review.” New York Times, January 29, 2010, C25. Review of Greenberg Van Doren Gallery exhibition.

Glueck, Grace. “Art in Review; John McLaughlin.” New York Times, September 23, 2005, n. pag. Review of “Birth of the Cool: California Art, Design and Culture at Midcentury” in Addison Gallery of American Art.

Harithas, James. “Painting at the Degree Zero.” Art News, November 1968, 52-53, 56-71. Review of John McLaughlin exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Johnson, Ken. “Art in Review; ‘Four Abstract Classicists’.” New York Times, June 22, 2001, n. pag. Review of Gary Snyder Gallery exhibition.

———. “Store in a Cool, Fertile Place: 1950s California.” New York Times, March 21, 2008, n. pag.

Knight, Christopher. “The Plain and Simple Truths Within; For John McLaughlin, painting was a tool to unleash the viewer’s introspection. An exhibition takes a long overdue look at his contributions.” Los Angeles Times, July 28, 1996, 57-58. Review of Laguna Art Museum exhibition.

———. “Why L.A. painter John McLaughlin matters.” Los Angeles Times, October 1, 2011, n pag. Brief appreciation for McLaughlin.

———. “Art: Pacific Standard Time / Critic’s Notebook; An unsung visionary master; Some of John McLaughlin’s works are in the exhibitions, but the postwar artist merits a major retrospective of his own.” Los Angeles Times, October 2, 2011, E.1. Analysis of the artist’s work in Pacific Standard Time.

———. “Pacific Standard Time: Review; L.A. inspiration; The Light and Space genre, which sprang up in and around Venice Beach, receives a beautiful, fascinating survey in a different California metropolis.” Los Angeles Times, October 5, 2011, D.1. Review of PST “Light and Space” exhibition regretting the absence of McLaughlin.

———. “Critic’s Notebook; Term limits on Abstract Classicism; ‘Hard-edge’ paints the truest picture about LACMA’s ‘Four Abstract Classicists’.” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 2014, D.1. Review of LACMA reprise of Abstract Classism arguing that the term is a misnomer.

Kramer, Hilton. “A Survey of California Art.” New York Times, June 19, 1977, D27. Review of “Painting and Sculpture in California: The Modern Era” formed by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and shown in Washington’s National Collection of Fine Arts.

———. “Art: Drawings by a ‘Disciple’ of Gorky.” New York Times, September 21, 1979, C18. Review of an André Emmerich Gallery exhibition.

Langsner, Jules. “Art news from Los Angeles.” Art News, January 1964, 50. Review of John McLaughlin exhibition at Pasadena Art Museum.

Muchnic, Suzanne. “Art Review ‘Colorforms’: An Old-Fashioned Salute.” Los Angeles Times, June 3, 1985, 1. Review of an exhibition at Security Pacific Bank.

Nordland, Gerald. “From Dirge to Jeer.” Arts Magazine, February 1962, 50-52. Review of John McLaughlin exhibition at Felix Landau Gallery.

Seldis, Henry J. “Precise Forms Mark Style.” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1959, E7. Review of the Abstract Classicist exhibition at LACMA.

———. “Contemplation Goal of ‘Total Abstraction’.” Los Angeles Times, February 11, 1962, A24. Review of an exhibition at Felix Landau Gallery.

———. “McLaughlin—A Gateway to Ourselves.” Los Angeles Times, July 15, 1973, P60. Review of the retrospective exhibition at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art.

———. “John McLaughlin, 1898-1976.” Los Angeles Times, March 26, 1976, E7. Obituary.

Smith, Roberta. “John McLaughlin”. Artforum, May 1974, 72. Review of McLaughlin exhibition at the Whitney New York.

Wilson, William. “Mystical Calm in Art Work.” Los Angeles Times, March 7, 1966, C4. Review of a Landau Gallery exhibition.

———. “Exhibit of ‘Quiet Master’.” Los Angeles Times, April 4, 1971, C61. Notes on an exhibition opening at University of California at Irvine.

Young, Joseph E. “Los Angeles.” Art International, October 20, 1970, 72. Review of Landau Gallery exhibition of John McLaughlin.

Interview

Karlstrom, Paul. Oral history interview with John McLaughlin, July 23, 1974. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Websites

Buddha-nature — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddha-nature#Zen_Buddhism

Pauli Exclusion Principle — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauli_exclusion_principle

There is a direct correspondence between this principle of quantum mechanics and the Zen Buddhist concept of everything is within everything else, as McLaughlin termed it “the relatedness of everything.”

COMMENTS

John McLaughlin, leading member of the Hard-Edge contingent in Southern California (they call themselves "Abstract Classicists"), came to his approach by way of exposure to the art and thought of [Asia]. A clue to his aspirations was succinctly stated by him once in a remark to this writer. Recalling his first encounters with Far Eastern paintings, he said, "I could get into the pictures and they made me wonder who I was. Western painters, on the other hand, tried to tell me who they were." It is McLaughlin's intention to create works of art that open the way to a contemplative state of being by engaging the spectator with the picture as a pure experience rather than by resorting to shadows of the visible world or by astonishment with the skill of the artist as a performer.

His retrospective exhibition of paintings and of color lithographs from 1948 to 1963 at the Pasadena Art Museum provides an illuminating demonstration of the persistent and subtle creative processes entailed in the attainment of pure forms which involve the spectator on their own reticent terms. Only after protracted efforts was McLaughlin able to achieve simplicity and economy of means. This absolute simplicity of square and rectangular forms in flat "clean" color, positioned in parallel bars or at right angles to each other, has been achieved through deliberation, much editing and concentrated focusing of the artist's sensibility on the relationships of the color forms to each other.

The creative act for McLaughlin is almost wholly internal. The application of paint to the surface is simply a matter of completing the idea. At first glance the paintings suggest variations of Mondrian or Malevitch (incidentally McLaughlin acknowledges them as forbears). But the differences between the 65-year-old Precisionist and his ancestors are significant. They reside primarily in the erasure by McLaughlin of any suggestion of space as a container. In a McLaughlin, color forms are not shapes on a surface that are seen as being "in space." Planes, space, forms are one and the same, indissoluble.

- Jules Langsner, "John McLaughlin" in "Los Angeles", Art News, January, 1964, p. 50

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

John McLaughlin sought pure abstraction in his art. He has said, “I want to communicate only to the extent that the painting will serve to induce or intensify the viewer’s natural desire for contemplation without benefit of a guiding principle.” McLaughlin’s first solo museum exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1956 featured asymmetrical, rectilinear paintings of unmodulated grays, yellows, pale blues, and blacks. Increasingly, McLaughlin’s work tended towards greater symmetry and simplicity, achieving a balanced state of substance and void.

In 1978 the artist June Harwood donated McLaughlin’s #12 to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in memory of Jules Langsner, whom she had married in 1965. Langsner curated the exhibition Four Abstract Classicists in 1959 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which presented McLaughlin’s work alongside that of fellow hard- edge painters Karl Benjamin, Lorser Feitelson, and Frederick Hammersley.

- Contemporary to Modern, 2014