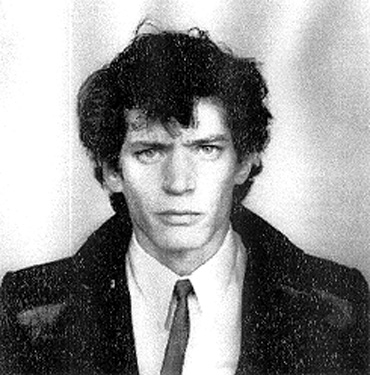

Robert Mapplethorpe

American, 1946-

Self-Portrait, 1980

silver gelatin print

"If I photograph a flower or a cock, I’m not doing anything different.” - Robert Mapplethorpe

COMMENTS

A product of the progressive 1960s, Mapplethorpe carried forward through his adult life the liberal lifestyles that defined that era. He was a pleasure seeker who indulged his senses, not as a means of self-destruction but for the purpose of experience. As an aesthete, the physical attributes of his living and working environs were critical. An impassioned collector, as noted earlier, he had amassed by the mid-1980s a substantial and diverse art collection, including among many things, vintage photography of the 1920s and 1930s, European and American furniture, and glassware and ceramic art of the 1940s and 1950s. Mapplethorpe shared Rady’s appreciation for modern design, and the work of many of the movement’s practitioners whom she grew up admiring—Isamu Noguchi, Herman Miller, George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames, Gio Ponti—had a presence in his loft/studio.

Mapplethorpe’s still lifes, a large and significant aspect of his oeuvre, cannot be understood apart from his explicitly homoerotic figurative works. The flowers and figures are two sides of the same coing. In this regard, a comment Mapplethorpe made about his eclectice taste in collectins is relevant: “The real challenge is to take many periods and come up with an aesthetic that runs through them all.” Applied to his own work, the idea is reflected in the fact that rhoughout his still lifes, figures, and portraits there is a unifying formal and conceptual approach.

As the reproductive structure of a seed-bearing plant, flowers were read by Mapplethorpe as interchangeable with male sex organs. Flower (1983), Eggplant (1985), and Calla Lily (1986) allude to the penis. If, as noted, the calla lily has been a subject for female artists of this century—Georgia O’Keeffe, Imogen Cunninghan, and now Rady, among them—it has also been a motif for male artists—Man Ray, Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth, for example. The androgynous form of the flower accounts for its complex sexual symbolism. While its soft, rounded contours and extreme concavity have been associated with the female form, its prominent stamen has bee viewed as masculine. Mapplethorpe, too, explored the theme in depth, but from a homosexual perspective. Fascinated with reworking clichés, he found great potential in the calla lily, which at least since the flamboyant days of Oscar Wilde has been associated with homosexuality. This particular association with Wilde has bee made clear in the many caricatures of the writer in which this symbol is part and parcel of his effeminate depiction.

While Mapplethorpe’s still lifes are resplendent, they posit complex ideas about sex, gender, and related stereotypes. A sensuous classicism is the style in which Mapplethorpe deliberately created sexual metaphors, simultaneously extending and challenging the foundations of formalism as artists have been doing over the last twenty years. The resulting contradictions, complexities, and ambiguities that coexist in his work, as they do in Rady’s, evidence how it, too rests on the cusp between modernism and postmodernism.

Transcribed by Ricki Morse, March, 2004

Robert Mapplethorpe was born in 1946, the third of six children. He remembered a very secure childhood on Long Island, which he summed up by saying, “I come from suburban America. It was a very safe environment, and it was a good place to come from in that it was a good place to leave.” He received a B.F.A. from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he produced artwork in a variety of media. He had not taken any of his own photographs yet, but he was making art that incorporated many photographic images appropriated from other sources, including pages torn from magazines and books. This early interest reflected the importance of the photographic image in the culture and art of our time, including the work of such notable artists as Andy Warhol, whom Mapplethorpe greatly admired.

Mapplethorpe took his first photographs soon thereafter, using a Polaroid camera. He did not consider himself a photographer, but wished to use his own photographic images in his paintings, rather than pictures from magazines. “I never liked photography,” he is quoted as saying, “Not for the sake of photography. I like the object. I like the photographs when you hold them in your hand.”His first Polaroids were self-portraits and the first of a series of portraits of his close friend, the singer-artist-poet Patti Smith. These early photographic works were generally shown in groups or elaborately presented in shaped and painted frames that were as significant to the finished piece as the photograph itself. The shift to photography as Mapplethorpe’s sole means of expression happened gradually during the mid-seventies. He acquired a large format press camera and began taking photographs of a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. These included artists, composers, socialites, pornographic film stars and members of the S & M underground. Some of these photographs were shocking for their content but exquisite in their technical mastery. Mapplethorpe told ARTnews in late 1988, “I don’t like that particular word ‘shocking.’ I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before…I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them.”

During the early 1980s, Mapplethorpe’s photographs began a shift toward a phase of refinement of subject and an emphasis on classical formal beauty. During this period he concentrated on statuesque male and female nudes, delicate flower still lifes, and formal portraits of artists and celebrities. He continued to challenge the definition of photography by introducing new techniques and formats to his oeuvre: color Polaroids, photogravure, platinum prints on paper and linen, Cibachomes and dye transfer color prints, as well as his earlier black-and-white gelatin silver prints.

Mapplethorpe produced a consistent body of work that strove for balance and perfection and established him in the top rank of twentieth-century artists. In 1987 he established the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to promote photography, support museums that exhibit photographic art, and to fund medical research and finance projects in the fight against AIDS and HIV-related infection.

From the web site: The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc.