Paul Manship

American, 1885-1966

Flight of Night, 1916

bronze

17 3/8 x 12 7/8 x 6 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. George M. Newell

1946.5.1

Undated photo of Manship.

"His figures, his draperies invariably strike one, in the first place, as being drawn, rather than modeled. In Manship, the silhouette is triumphant." - Royal Cortissoz

RESEARCH PAPER

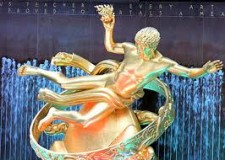

The Flight of Night is a bronze statuette, finished in a green patina and is one of an edition of twenty (also done in brown and black patinas). The height of the figure measures 1’ 1 ", while the length is 1’ 1 ". The globe upon which the figure rests is 3" in diameter. It was sculpted by Paul Manship in 1916 and given to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 1946, the gift of Mrs. George C. Newell.

The Flight of Night is composed of three parts, the topmost being a slender female figure, which is supported by a sphere, which in turn rests upon a three tiered square black marble base. The torso of the figure is nude from the waist up, and holds her arms above her head, bent at the elbow, with her left hand touching the top of her head. From her hip down, she is wearing a long drapery, which encircles and envelops her legs, creating voluminous folds; this fabric extends behind her in a long, upward-arching train. One of the lower portions of drapery rests atop the sphere, thus supporting the figure.

This allegorical figure of Night (the mother of Death?) seemingly flies through space above the globe, and is best viewed from the front, where the curving silhouette of the garment is displayed most effectively. Manship has put the body’s center of gravity off balance with relation to the globe below. The feeling of movement is actually in a backwards direction, where the eyes of Night are focused, rather than forward, where the body extends in space. The viewer’s eye begins with the head and upper torso and is swept down along the graceful figure and away on the smooth crescent art of the trailing folds of the garment.

Paul Manship was born on Christmas Eve, 1885, in St. Paul, Minnesota, and received his earliest artistic training there at the Mechanical Arts High School and at St. Paul Institute of Art. He had originally hoped to become a painter, but discovered that he was colorblind. Manship worked as an engraver and illustrator after high school, but sculpting was where he felt his talents could best be expressed. So he went to New York, becoming an apprentice to Solon Borglum, whose brother Gutzon Borglum was responsible for the colossal Mt. Rushmore sculptures. In Borglum’s studio he gained a thorough anatomical knowledge and an appreciation for monumental achievements, both of which would figure in his later work.

Next he studied life drawing with Charles Grafly in Philadelphia, and modeling technique with Isidore Konti. It was Konti who persuaded him to enter the scholarship competition for the American Academy in Rome, which he subsequently won in 1909. The three years he spent studying and traveling in Italy and Greece and Egypt were to be a revelatory experience in his continuing sculptural apprenticeship. He was quite taken with the dignity and restraint of archaic sculpture, which led to a lifelong appreciation of Greek, Egyptian, Etruscan, and Indian culture. He believed that design was learned in the process of creation, not to be studied as a distinct discipline, and thus endeavored to become an expert craftsman.

Manship returned to America in 1912, exhibiting a collection of small bronzes at the Architectural League of New York gaining much critical acclaim and enthusiastic public support. In the next few years, he received important commissions for garden architectural sculpture, and continued to produce small bronze groups and figurines of exquisite workmanship, which were exhibited at art museums throughout the country. His first one-man show in New York was so well received in 1916 that a fashionable craze for his work developed. The peculiar fascination of Manship’s early work lay in the combination of naturalness of pose with a superficial stylization of anatomy and drapery. Strong design, organized decorative patterns, and especially crisp modeling distinguished his work. Each of these qualities constituted a break with the sculptural forms that were then flourishing in the United States.

In the early twenties Manship’s style evolved towards greater realism and less decorative detail. He worked abroad in England and France and received many portrait commissions. In 1927 he returned to New York to occupy himself with a succession of monumental sculptural works for governments and corporations, including his famous Prometheus fountain for Rockefeller Plaza. Dedicated in 1938, it showed his continued emphasis on line and also the massiveness characteristic of his later work.

Paul Manship was a prolific artist, as well as an extensive lecturer and member of many art associations, professional artists organizations and advisory commissions to the government on the arts. In all, Manship produced some 700 sculptures ranging in size from a few inches to heroic proportions. He worked until the day he died, unexpectedly, in 1966. He was equally skilled in all branches of the art of sculpture, from medal to monument. Birds, animals, and plant forms, as well as the human figure, were appropriate subjects to him.

Reflecting on his career in a letter to his nephew in 1952, Manship said: "I had no great talent but was free and unencumbered; the right man for the right time." He also was frequent to note, "Art is a series of recipes." These "recipes", his artistic vocabulary that he used to speak to the public of his time, were not as widely embraced in the second third of the twentieth century; his "right time" had waned. However, the quality and inspiration of his work did not change, or become less so; it was merely the time within which he worked that had marched onward.

The essential unity of all "primitive" (or pre-classical) art was now one source of Manship’s inspiration, and his emphasis was on form, rather than subject matter or emotion. In 1916, the year Manship was to call the advent of his mature style, he began to experiment with elements of the art of India. We can see in Flight of Night that from the orient he learned the concept of movement in space, its emphasis on highly decorative surfaces, its look of sinuous grace, and a tendency to use silhouette to achieve purity of line. Royal Cortissoz, an art critic at the New York Herald Tribune remarked: "His figures, his draperies invariably strike one, in the first place, as being drawn, rather than modeled. In Manship, the silhouette is triumphant." Manship had used almost the same words in 1912, in his paper on the decorative value of Greek sculpture: "We feel the power of design, the feeling for sculpture in line, the harmony of the divisions of spaces and masses- the simplicity of the flesh admirably contrasted by rich drapery, every line of which is drawn with precision. It is the decorative value of the line which is considered first. Nature is formalized to conform with the artist’s idea of Beauty…the artist has subordinated everything to this formal composition. The entire statue can be considered as the decorative form upon which all detail is drawn rather than modeled."

The Flight of Night shows Manship to have been very adept technically, and he was one of the first important American sculptors to treat bronze as a hard material, revealing the craftsman’s hand in chasing the metallic surfaces. His bronze further suggests, in its flow of line, the flow of the molten metal. Much of the work for his bronzes that other sculptors would have done in clay he did by carving and filing the clean resistant surface of plaster.

Manship also shows a wonderful sense of design. The enchanting grace and freedom of action, controlled and given sculptural quality by impeccable composition, is a worthy achievement. His entire body of work shows an energy and exuberance and harmonious balance which is quite pleasing to the eye, and the SBMA Flight of Night is no exception.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Adrienne Basler O’Donnell, April 1985

Bibliography Books: Casson, Shirley. Twentieth Century Sculptors. London: Oxford University Press, 1930. Murtha, Edwin. Paul Manship. New York: Macmillan Company, 1957. Periodicals: Manship, Paul. "The Sculptor at the American Academy in Rome," Art and Archaeology vol. 19, Feb. 1925, p.89-92. "Paul Manship’s Work in Sculpture," The Outlook, vol. 112, March 8, 1916, p.553. "Paul Manship’s Latest Work," Current Opinion, vol. 78, April 1925, p.432-435. Wilson, Mailin, "Paul Manship: The Flight of Night," The Toledo Museum of Art: Museum News, vol. 17, no.3, 1974, p.59-61Exhibition and Collection Catalogues: Minnesota Museum of Art, "Paul Howard Manship, An Intimate View", St. Paul, 1972. The National Collection of Fine Arts, "Paul Manship", Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 1966. The National Sculpture Society, "Paul Manship", New York, 1947. The Smithsonian Institution, "A Retrospective Exhibtion of Sculpture by Paul Manshi[p," Feb. 23-March 16, 1958, Washington, D.C.

Manship often went to classical mythology for his subjects. His art is notable for its emphatic musculature and polished contours. Among his works are the large gold Prometheus (1934) at Rockefeller Center, New York City.

COMMENTS

Paul Manship often used a flying figure to symbolize the passage of time. The woman in Flight of Night is probably Artemis, Greek goddess of the hunt and moon, who was chased from the sky every morning by her twin brother, Apollo.

- Information from the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This seemingly weightless figure is a first-rate example of Manship’s refined technique. The figure is likely a personification, and perhaps even identifiable as Artemis, the goddess of the moon who was chased away by her twin brother, Apollo, god of the sun. Manship was an admirer of ancient art, especially Egyptian, Archaic Greek, and Etruscan. In this piece, traces of all of these sources can be detected, as filtered through a distinctly modern, Art Deco sense of design. One of the finest works of the artist’s early maturity, this sculpture is one from an edition of twenty, and can also be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian, and the National Gallery of Art.

- Highlights of American Art, 2020