Stanton Macdonald-Wright

American , 1890-1973

Yin Synchromy No.3, 1930

oil on canvas

34 x 40 1/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. John D. Graham

1949.22.2

RESEARCH PAPER

The painting. Yin Snychromy No.3, is a handsome oil painting on canvas which was donated to the Santa Barbara Art Museum by Mrs. John D. Graham in 1949. The work was painted in 1930 by Stanton Macdonald-Wright, cofounder of an interesting art movement in our century- Synchronism- and had the distinction of appearing in a retrospective exhibition of the artist’s paintings at the Smithsonian in 1967.

"Synchronism" is a word coined by Morgan Russell and Macdonald-Wright which means "with color" as symphony means "with sound." The two men vehemently opposed the monochromatic works of the Cubists and set out to achieve the orchestration of pure, vibrant, intense, saturated color. Composition was a process dictated by the application of color, rather than the other way around.

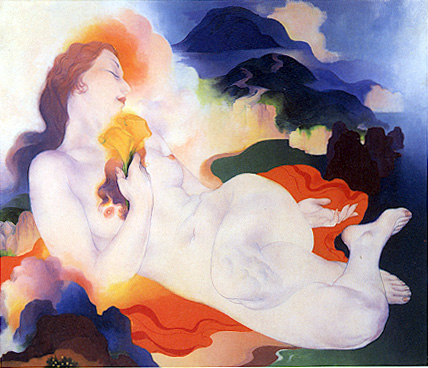

The influence of the Orient upon the California artist is readily apparent with the inclusion of "yin" as part of the painting’s title, "yin" being the Chinese symbol for "female." Dominant in the composition is a curvaceous nude against a strongly contrasting seascape background. The female seems to be at great ease with the world of nature; and the exclusive use of curvilinear lines serves to unite the two, much as "yin" and "yang," the male symbol, are usually represented as two comma-shaped forms interlocked in a circle.

The artist has achieved a remarkable coalition of the ancient art of the Far East and of the modern art of the West. The nude is in repose, eyes closed, with face cast backward. The body is painted with loving tenderness and simplicity; she is clasping yellow calla lilies in one hand, and her hair is long and flowing. The surrounding clouds lend a meditative quality to the painting. It is both abstract and not abstract. It has a feeling of hidden reality. The brush is used to outline the figure with a minimum of detail, an Oriental technique. The lightness in color of the woman and the diffused clouds about her are offset by the gorgeous gamut of oranges, browns, greens, purples and blues in the background. The view of land, ocean and sky is a sweeping one, much like those around Big Sur. Strong curvilinear lines heighten the harmonious effect.

This painting reflects some of the statements made by Macdonald-Wright: "The thing that’s interested me is the balance of color. I think if you take any picture of mine and for the moment obscure from your thoughts all colors except one, you will find that color balanced within itself…and one of the things that interests me particularly about Chinese art is the balancing…of large empty masses of light and dark…I think every composition that I have ever made, like all my earliest work, is figurework."

Also, in 1954 he wrote: "I am fundamentally interested in what to me is beauty- everywhere, in women, animals, the sea and hills, in ideas, music, architecture, poetry. I am not at all stylish, for my pictures are always hoping and searching for beauty; indeed this is the way I paint and why."

Stanton Macdonald-Wright was born in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1890 and began the study of art under private tutors at the age of five. When he was ten his family moved to Santa Monica. Evidently his maverick nature surfaced quite early for he was expelled from a number of private and public schools there. When he was fourteen he ran away from home, signed on as a cabin boy in a "windjammer" bound for Nagasaki, Japan, but deserted ship at Honolulu and lived for a short time with the natives of Maui. Then he returned to Los Angeles, but soon left for Paris where he studied at several art academies. He maintained, however, that he did most of his real studying in the great museums of Europe. In his salad days in Paris he was the epitome of the defiant young rebel. He held forth in cafes and studios, determined at all cost to fashion a mode of expression fully twentieth century in spirit and concept. Along with Morgan Russell, a fellow American, Macdonald-Wright launched the Synchromist movement in 1912, and they exhibited their paintings in Europe and in New York the following year. In 1916 Macdonald-Wright left for New York and held exhibitions there.

In 1919 he returned to Santa Monica and produced the first full-length stop-motion film ever made in full color, drawing for it at least five thousand pictures, each three by four feet, in pastel. Later, an expert, Walter Wright (no relation) joined him in developing an additive color process for motion pictures which was patented under the name of the Synchrome Corporation.

Not satisfied with the orientation of modern painting and finding his own Synchromism stultifying, Macdonald-Wright reached out enthusiastically into new areas of world art. From 1930-1935 he painted a mural for the Santa Monica library which is now in the permanent collection of the National Collection of Fine Arts at the Smithsonian. In 1935 he became the Southern California Director of the W.P.A. Art Project, resigned in 1937 because of illness and went to Japan, returning a year later to work for the W.P.A. as Technical Advisor in seven western states. He never stopped painting, although he didn’t exhibit for more than 30 years. He began to pursue the study of Chinese and Japanese art and religion and spent some time in the Orient. In 1953, at the age of 63, he felt he had overthrown his previous misconceptions, only to discover that he had made a great circle, coming back to an art superficially like his early work, though more mature. In 1954 he re-entered the exhibition field, and a major exhibition was held at the L.A. County Museum in 1956. His work was also presented abroad and in various U.S. galleries, most notably the Smithsonian in 1967. A showing was also held at the SBMA that year. A heart attack in 1962 forced him to reduce the size of his paintings, and he died in 1973.

Stanton Macdonald-Wright was one of the leaders in a group that was first to produce abstract paintings in America that could stand on their own merit. It was only when the American artist learned to trust entirely to his painterly instinct and to the means of painting itself, long the trade of the French artist, that this country could become a dominant force in modern art.

Bibliography

Agee, William C., "Synchromism, the First American Movement." Art News, vol. 64

(Oct. 1965)

Langsner, Jules, Stanton Macdonald-Wright. Los Angeles: Esther Robles Gallery

Catalogue, 1964.

Scott, David W., The Art of Stanton Macdonald-Wright. Washington, D.C.:

Smithsonian Press, 1967.

Wight, Frederick, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, A Retrospective Exhibition, 1911-1970.

Los Angeles: Grunwald Graphic Arts Foundation, 1970

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Docent Council by Virginia Cleveland, April, 1978.