Helen Lundeberg

American, 1908-1999

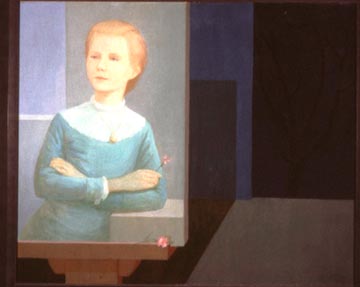

The Portrait , 1953

oil on canvas

30 × 36 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr and Mrs. Thomas C. McCray

1959.50

Lundeberg photographed by Lou Jacobs, Jr.,1949

RESEARCH PAPER

Helen Lundeberg, who has long been one of Los Angeles's most significant modernists, celebrates her eightieth birthday this year (1988). She began her career at a time when the city could claim few progressive artists. Eventually she attained a national reputation more notable than those of most other local artists of her generation. She did so by quietly pursuing her own vision.

Lundeberg has created a remarkable oeuvre that embodies many dichotomies. A subjective strain predominates, but her visual statements are also always about life's universals. The distinctly personal nature of her work, however, did not prevent her from participating in contemporaneous developments in the world of art. One of the artistic vanguard, she nevertheless early chose to base her modernism on a strong classical foundation.

She began exhibiting publicly in 1931 and only two years later was given her first solo exhibition. Along with Lorser Feitelson, who was first her teacher and later her husband, she issued in 1934 the manifesto New Classicism . Also known as "subjective classicism," the aesthetic soon became identified as "post-surrealism," due to its debt to the European phenomenon. Yet unlike European surrealists, who promoted the role of accident and the unconscious in the creation of a work of art, Lundeberg and Feitelson infused their painting with a sense of order and rationality. This they did by deliberately using the principle of association to create ensembles from what appear to be random arrangements of unrelated objects. Though such works cannot be literally "read," their meaning is suggested by the type of objects selected and their placement within a composition.

At this early phase in Lundeberg's development, the subjective had already found its prominent place, as had the mystery, reserve, and classical order that so often pervades her images. It was this early aesthetic that brought Lundeberg her first national recognition: the group of postsurrealists that formed around her and Feitelson was accorded exhibitions at museums in San Francisco and Brooklyn in 1935, and Lundeberg was asked to participate the following year in the landmark Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Continuing to explore post-surrealism in the 1940s, she was repeatedly invited to show her work in exhibitions throughout the country.

Another, less creative, and less self-assured artist might have been content to continue in the idiom that established her reputation, but not Helen Lundeberg. By the 1950s she had abandoned the aesthetic of her highly programmatic, post-surrealist canvases. Still concerned with reality on an abstract, conceptual level, she began to explore the formal potential of the physical world's appearance. She became intrigued by the way a few flat geometric shapes could be arranged to create the illusion of the third dimension. Because of her preference for classical form, she had always conceived of the material world in simplified terms, but now her environment became even sparer, limited to interiors devoid of all but a few pieces of furniture or to wide-open, empty landscapes. Eventually she developed the minimalist, yet poetic, hard-edge style that has since distinguished her art.

Although Lundeberg's mature paintings are akin to those of the Los Angeles abstract classicists Karl Benjamin, Lorser Feitelson, Frederick Hammersley, and John McLaughlin - her work remains distinct from theirs. Unlike these hardedge painters, Lundeberg never developed a completely nonobjective art, insisting that some suggestion of reality be retained. Painting never became a purely intellectual exercise for her. Moreover, due to her frequent use of curvilinear forms and the nuances of her soft, tonal palette, Lundeberg's style is more sensuous than the art of other Los Angeles geometric abstractionists.

Despite these transformations, Lundeberg's art demonstrates a strong continuity of themes. The recurrence of self-portraits in her oeuvre indicates the degree to which her personality dominates. In the postsurrealist compositions of the 1930s and early 1940s she represented herself in profile and eventually as a shadow. In the more complex compositions with many different types of objects, Lundeberg's presence was often limited to only one part of her body, usually her hand holding a paint brush or flower. More oblique references to the artist were the inclusion of her own paintings in interior scenes, either hanging on walls or set on easels. The Portrait in SBMAs collection is a good example of the later. During the late 1950s and 1960s, when she pared her visual statements down, she continued to recycle the basic objects of her material environment: tables, mirrors, her own canvases, doorways, and desert views. The artist and her world became so familiar that the inclusion of the figure of Lundeberg was no longer necessary for understanding the self-referential nature of her artistic statement. Eventually her paintings alluded to her presence even when she was absent.

The number of works in which she portrayed herself as a painter demonstrates how important the concepts of creativity and illusion have been to her. Lundeberg equated the process of creating a work of art with birth and with the generative cycle of nature, including in these compositions images of plant forms in all stages of development, botanical and biological diagrams, and landscapes with floating celestial orbs. Later she explored the notion of creation through a single type of object; for example, in the Planet Series of the 1960s, she enlarged the spheres of earlier canvases and presented them in a square format. The heavenly bodies floating in a mysterious, blackened atmosphere were meant as emblems of the eternal, while the shape of the canvas symbolized the transitory.

The different levels of reality, as well as the duality of reality and illusion, have also been a strong undercurrent. Early in her development she began to play the visual game of a painting within a painting. In her interiors she hung painted portraits that were often re-creations from old photographs, while sometimes a reflection in a mirror or a shadow cast on a wall served as the physical evidence of a person who was not actually present. In the interiors from the 1950s the artist set one of her paintings of a landscape next to an aperture through which the actual scene could be viewed, thereby juxtaposing the painted image with the supposedly real one. In actuality, however, both landscapes were the result of Lundeberg's own artifice. At the end of the following decade she further blurred the distinction between the real and the perceived in her "figure landscapes," canvases in which colored, horizontal bands represented both a recumbent female torso and a sweeping vista.

Lundeberg's paintings since the 1960s appear to be simple, visually pleasing arrangements of flat, geometric shapes in a limited, almost monochromatic palette; however, these compositions are as structured, complicated, and mysterious as her early, surreal work. Imagery and color are manipulated to evoke moods. A poetic silence, order, and calm usually pervade these late interior and exterior spaces. Lundeberg has looked beyond the ordinary, creating an art that can be appreciated on multiple levels and understood to a certain degree, but despite the contemplation her art suggests and, in fact, requires, in the end it always remains an enigma.

Discription of the Work

Filling the left side of this picture is a painters easel upon which rests a painting of a young woman with her arms folded across her chest and a small pink flower in her right hand. She has blond hair, fair complextion, and wears an aqua blue dress with high neck. Around her neck hangs a gold chain that holds a small, gold charm. At the corner of the easel is another or the same pink flower held in the young womans hand. To the right of the easel is a room with an open window through which a leafless tree can be seen silhouetted against a purple sky.

Biographical Information

Born in Chicago, Lundeberg studied art at the Stickney School of Art in Pasadena. There she was strongly influenced by her teacher, Lorser Feitelson, whom she later married. She did realistic mural and easel projects for the Federal Art Project from 1933-1942, while continuing to do more experimental work privately. A New Deal mural of hers in Orange County's Fullerton recently underwent restoration. Her work has been shown in major national exhibitions since the late 1930s. In 1959, Santa Barbara Museum of Art had a solo exhibition of Lundebergs work. The American band, Sonic Youth have a song called "Helen Lundeberg" on their 2006 album Rather Ripped .

Bibliography

Fort, IIene Susan. 80th A Birthday Salute to Helen Lundeberg , Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Catalogue published.

Transcribed from SBMA Docent files 2008, LG.