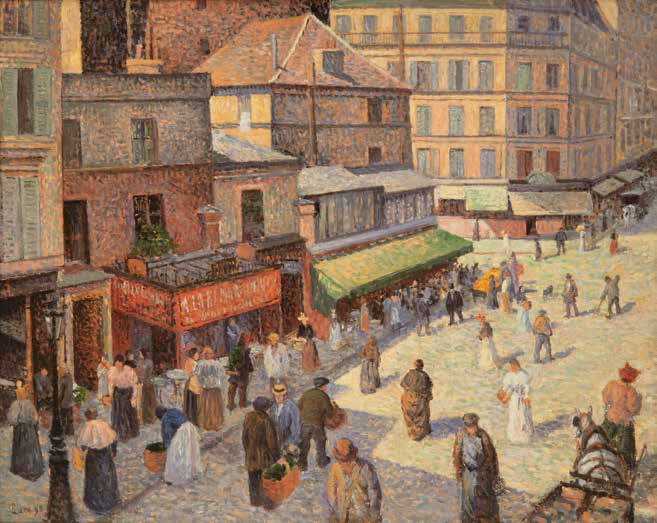

Maximilien Luce

French, 1858–1941

Rue des Abbesses, 1896

oil on canvas

25 1/2 x 31 3/4 in.

Collection of Robert and Christine Emmons

Maximilien Luce – Self-Portrait, ca. 1888

“The portrait of [Charles] Laval is very self-assured, very distinguished, and will be precisely one of the paintings you speak of, which one takes before the others have recognized the talent. I think it excellent that you’re taking a Luce.”

- Letter to Theo, 11 or 12 November 1888

COMMENTS

It was probably through Cavallo-Peduzzi, a generous patron of the arts, that Luce later met Georges Seurat (1859-1891), whose technique of Divisionism (also known as Pointillism) was soon taken up by both painters, as well as by Lèo Gausson (1860-1944). The rendering of form, light and spatial recession through the scientific application of dots of pigment was meant to simulate effects recently discovered in the fields of optics and color theory. Another aim of the Neo-Impressionists, as practitioners of this revolutionary technique were called, was clarity and simplicity of form, as a corrective to the empirical realism of the Impressionists. In 1884, Luce undoubtedly saw Seurat’s painting, “Bathing Scene at Asnières”, at the first salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, an organization founded by, among others, Luce’s friends Auguste Lancon and Paul Signac (1863-1935). Two years later, Seurat exhibited his seminal “Sunday Aflernoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte”. In later years Luce would have frequent access to this masterpiece when it came into the possession of his friend Lucie Cousturier, the subject of several portraits by his hand, including the memorable full-length likeness in this exhibition [Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, May 6 – June 7, 1997].

In 1887 Luce moved to Montmartre. His submissions that year to the third salon of the Indépendants were for the most part painted in the Divisionist style. These pictures were well received by Seurat, Pissarro and the influential critic Felix Fénéon, who a year later gave Luce his first one-man show on the premises of “La Revue Indépendante”, the leading journal of the Neo-Impressionists. At the exhibition, Signac, who was to become the spokesman for the same group, purchased Luce’s so-called “Toilette”, a painting now in the Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva. The composition depicts a laborer washing after a day’s work, a humble theme that attains monumentality thanks to Luce’s powerful composition and skill in the demanding pointillist technique.

By 1888 Luce had attained prestige and recognition. He was befriended by other Neo-Impressionist painters, namely Albert Dubois-Pillet (1846-1890), Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910), Hippolyte Petitjean (1854-1909), Louis Hayet (1864-1940) and Charles Angrand (1854-1926). That July he and Gausson stayed at Eragny with Pissarro, who was to remain a loyal friend. In the spring of 1892, the two artists made a painting trip to London, as Luce was recovering from the trauma of an unhappy romance. A year later, Luce met a young Breton woman, Ambroisine Bouin, who posed for him often and eventually became his common-law wife.

By the late 1880s Pissarro, who had converted almost overnight to pointillism after meeting Seurat, was already experiencing doubts about the value of the style as far as his own painting was concerned. He felt that scientific divisionism hampered a painter’s spontaneity. As a result, he progressively abandoned the technique, making his brushstrokes larger and looser and his palette more varied. That development, and Pissarro’s commitment to recording the life of the peasantry, were to have a strong impact on Luce’s style. This tendency is evident in the artist’s intimate painting, “The Lesson”.

Besides a common stylistic evolution, Pissarro and Luce shared an abiding empathy with the hopes and aspirations of the working class. The anarchism they espoused was a form of utopian socialism that bore little relation to the bomb-throwing, nihilist activities with which the movement is usually associated. As John Rewald writes, Seurat, Signac and other artists in their circle were “idealists, not agitators.” Like the work of Jean-Francois Millet, their painting often reflects passionate solidarity with the lot of the common man. By contrast, the aesthetic or symbolist content of much Neo-Impressionist art held little attraction for them.

- Eliot W. Rowlands, Maximilien Luce: The Evolution of a Post-Impressionist, New York: Wildenstein, 1997, 18-20

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Luce’s career traversed the generation of Van Gogh’s “Petit Boulevard” painters well into the first half of the 20th century. This painting was made long after Van Gogh’s death in 1890, but we can already see the application of a pointillist technique in the service of a more clinical objectivism. This sensation of detachment and autonomy of the world independent of subjective perception was singled out by the critic Félix Fénéon, who saw it as consistent with a Symbolist interest in universal, transcendental communication. To Fénéon, Georges Seurat was the quintessential ‘Neo-Impressionist,’ seeking a pictorial technique and idiom that emphasized the eternal and not the transitory, as had the previous generation of Monet and the Impressionists. Luce fell into this camp.

Like Seurat, Luce considered himself an anarchist and was briefly imprisoned along with Fénéon in a government crackdown against suspected insurrectionists. He conceived of his art as in the service of and for the proletariat. The elevated viewpoint and looser adaptation of the pointillist dot in this street scene is reminiscent of the cityscapes of Pissarro of the 1890s. We do know from Van Gogh’s letters that, as early as 1888, Van Gogh was recommending the work of Luce to Theo: “I think it excellent that you’re taking a Luce. Does he by any chance have his portrait? That’s in case there’s nothing extraordinarily interesting—portraits are always good.”

- Through Vincent's Eyes, 2022