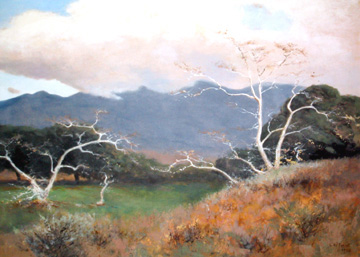

Lockwood de Forest

American, 1850-1932

California Coastal Range , 1923

oil on canvas

24 x 34 1/8 x 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of the Estate of Alice de Forest Sedgwick

1988.49.3

The colorful Lockwood de Forest

"I took up landscape painting as a profession when I was twenty largely due to Mr. Frederick E. Church…From that time I was a great deal with Mr. Church for ten years. This close association was the most important factor in my own development."

- Lockwood De Forest

RESEARCH PAPER

Biography

Lockwood De Forest was born into a cultivated New York family whose antecedents included Jesse De Forest, a Huguenot exile who had brought the first settlers from Holland to New Amsterdam in 1623. The De Forests prospered as shipping merchants around New Haven. In 1915, Lockwood’s grandfather moved his large family to New York. His father studied at Yale, married Julia Mary Weeks and produced four children in good order. Due to their parent’s influence, all four became associated with the arts in some way. Like many well to do families of the Gilded Age, the De Forests made frequent trips abroad, specifically to tour the great museums. As soon as the children were old enough they went along. Mother De Forest was especially desirous that her chicks acquire an art education and kept a detailed log of all the works they saw. A sample itinerary, for the three oldest children in 1868-69 involved a winter in Rome, Constantinople by April, on to Greece, a sail up the Bosphorus, the Danube to Vienna, on to Salzburg by way of Innsbruck, then to Northern Italy, finally returning to France for the voyage home in June.

De Forest, then nineteen, had already shown a strong interest in painting and it was during this tour that he began his first formal training in Rome with Italian landscapist, Herman Corrodi. More important for his development however was his "adoption" by the American artist, Frederick Edwin Church. The Church and De Forest families had a distant relative in common and had travelled together. Church had a studio in Rome and Lockwood became his devoted dog’s body, travelling with him on visits to all the sites of historical and artistic interest. During the stay in Athens, he accompanied Church on sketching expeditions at the Acropolis. It is very likely that Moonrise in Greece, a gift to SBMA from Mrs. Lockwood De Forest, was given to Lockwood by Church in fond memory of that time when young De Forest had helped him document his Greek experience with notes, color sketches and photographs. De Forest credits Church with his career choice in the following statement, "I took up landscape painting as a profession when I was twenty largely due to Mr. Frederick E. Church…From that time I was a great deal with Mr. Church for ten years. This close association was the most important factor in my own development."

Through Church, he met many important Hudson River School artists. Though he studied briefly with Thomas Hart, he began formal studies with Church by 1870, spending much time with him at his home, Olana, and on sketching trips up and down the East Coast.

Forgoing college altogether in order to pursue a career as an artist, he opted to accompany his parents on another grand tour, only this time with the specific goal of studying the architecture of the Middle East. His interest in the art traditions of the East was inspired by his mentor’s enthusiasm for the exotic and oriental. His initial research had begun in Church’s library at Olana. In 1875, the family left for Egypt and a trip up the Nile. There followed sojourns in Beirut, Jerusalem and Damascus. While his parents stayed in Damascus, he and his cousin took an arduous side trip to the ruins at Palmyra. In the three days there he painted fourteen studies in oil, as well as made numerous drawings. The trip was a profound experience for him, sealing his growing love and fascination with the East. He developed the notion, along with other late nineteenth century artist-travelers, that European influence was a "curse", as it brought industrialization and ugliness. Based on his impressions of the "unspoiled", he continued to champion third world cultures for the rest of his life. The work accomplished as the result of this trip established his reputation as a landscape painter. In 1878 his painting, The Pyramid of Sakkarh, which had already been exhibited at the Nation Academy in 1877, was included in the American contribution to the Paris Exposition of 1878.

On his return to the U.S., new possibilities presented themselves through his friendship with two kindred souls, Louis B. Tiffany and Candace Wheeler. Together they created a professional decorating firm called Associated Artists. De Forest had already remodeled his father’s house from ideas garnered from his trip to the East and he had also taken an active part in the transformation of Olana in the "oriental style". Tiffany had been so taken by Indian wood carvings he had seen in the British Museum, that he suggested that one of them go to India to seek materials and designs for their commissions. De Forest was a natural choice and after marrying Meta Kemble, who seems to have shared his enthusiasms to a remarkable degree, the two went off to India, not to return for two years. Originally conceived as a business venture, the experience came to involve him totally. The amateur connoisseur and buyer became an active sponsor and patron of Indian craft. He soon discovered that the craft articles he was looking for were rare. These articles, due to local custom were only made to order, and due to lack of sponsorship the craft itself was in danger of dying out. Purchasing antiques was also out of question as to sell them was a violation of caste. The particular craft, which most interested him, was the decorative carving on house fronts. In order to obtain the kind of product he wanted he realized he would have to start his own workshop. With the help of a high caste family in Ahmedabad, he commissioned local craftsmen and put them back to work. As soon as the shop was underway, he traveled with his bride throughout India and Nepal, checking out the local handcraft industries in each town. Eventually they visited Agra and the Taj, but were most intrigued by the city jail whose inmates manned a flourishing carpet weaving factory. De Forest was an avid collector of Indian jewelry, as it was one of the few items that could be got in the original. Most of his acquisitions were later sold to Tiffany. Reading the accounts of their travels, one can’t help but be impressed by the endurance and adventurous spirit of the young couple.

On returning from India, De Forest terminated his business relationship with his two partners. Tiffany, by then, was involved in experiments with glass and Wheeler was interested mostly in textiles. He continued his Indian operation in woodcarvings as well as metal craft and jewelry, eventually adding a carpet-weaving workshop. Soon he had established himself as a successful independent decorator. His book, Indian Domestic Architecture was published in 1885. The Ahmedabad workshop had filled the orders for his decorating business for ten years when De Forest returned to India with his wife in 1892. He found the workshop in thriving condition with forty to one hundred gainfully employed. The couple continued to explore out of the way places and to acquire another jewelry collection for Tiffany and Co. Without the commitments to Associated Artists and the drain of setting up a new enterprise, De Forest had more time on this trip to pursue his own art. The studies and sketches for a work in SBMA’s collection on the Taj Mahal likely date from this trip. The jewelry collection turned out to be a winner. Tiffany showed the entire group at the Colombian Exhibition of 1893. The Field Museum in Chicago purchased it. De Forest was awarded a medal at the exhibition for a carved teak room and furniture he had designed for Marshall Field.

Decorating commissions for houses in the East, Midwest and West continued to come to his New York City studio. The design of the dean’s residence at Bryn Mar College, which was completed in 1919, was one of the largest. By the 1900’s he was devoting more and more of his time to landscape painting. Sometime between 1889 and 1902 he began wintering in Santa Barbara. Eventually he designed and built a house at 1815 Laguna Street, settling there permanently by 1922. In the meantime, he continued to travel and paint extensively in the West. Between 1904-1911 he made trips to Mexico, which reminded him of India. His final trip to India was in 1913 in order to shut down his operations. There was less demand for Indian décor in the U.S. and his relationship with Tiffany and Co. had atrophied.

His Work:

During the first decade of the twentieth century, De Forest’s oeuvre consisted of studies of Long Island and scenery from New England which emphasized his love of skies and atmospheric effects, nocturnal scenes, and portraits of specific sites in the West, including the hills around Santa Barbara, coastal scenery of Carmel and Monterrey and inland California deserts, particularly Palm Springs. All of his sketches after 1900 were 9 _ x 14 " in size. Each uses an ochre ground color beneath thin, wash-like oil colors. The overlay partly accounts for "the sparkling vibrancy of the skies". The sketches were quickly executed, direct, spontaneous in drawing and brush stroke with the use of fresh, clear colors. The paintings were made up in the studio, occasionally some time later, from sketches made at the scene. His drawing is sensitive and accurate, the colors strong as he constantly strove for "objective effects". The expressed aim of his art was to convey through these "photographic effects" as he also called them, his own love of nature to the viewer.

During the summer of 1912 he traveled to Alaska to attempt a drastically different type of western landscape. The oil sketches received recognition long after De Forest’s demise largely through the efforts of Molly Lee, UCSB graduate in art history and the cooperation of the De Forest family. They were exhibited at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau, August 24 to October 2, 1988. During his lifetime a selection of his California and Alaska sketches were shown in the spring of 1913 at the St. Louis Museum and the Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis, but for the most part his work remained hidden from the public eye.

His Contribution:

Because of his experience of promoting and developing handicraft in India, De Forest was vitally interested in the pedagogical problems of industrial and craft education. He became an advisory editor for the publication, Handicraft, and wrote a book, Illustrations of Design, in which he shows how the most simple forms, the right angle, the triangle and the curve, form the harmonious combinations and repeating patterns of Islamic and Indian designs. He insisted on an egoless, unself-conscious state as a prerequisite for art making. In this he identified himself with the work ethic of the arts and crafts movement. He berated Western teaching methods, especially by rote memory. He felt the mind needed to be developed through the senses, hand and eye, starting with the very young. In this sense his ideas were congruent with Froebel and Montessori. The high quality of Indian art was due, he believed, to the caste craft system, which introduced children to the work at an early age. He was also critical of art museums, as they tended to fragment collections, which he felt needed to be seen in their entirety. Rather than "vast, bland spaces", he felt that museums of art should be more like those of the natural sciences and ethnography where you could "browse" for inspiration. He also critiqued collecting and collectors. He felt interest and commitment drove the true collector, not by wealth and personal display. He proposed that museums coordinate their collecting ventures and directions.

He gave his approach to painting and drawing a scientific cachet when he invented a drawing device, which allowed the person using it to trace the image before him on a framed glass, the same size of the paper, and mounted on an easel. In this way one could merely trace the angles of the orthogonals to achieve perspective. Perhaps this explains why his sketches were always of the same size.

De Forest’s aesthetic remained essentially that of a third generation Hudson River School. His goal was to achieve a supra-personal objectivity on canvas, suborning all subjective considerations in order to serve as a conduit for nature in all its manifest glories. Although uninfluenced by the most contemporary art of his time, (he was 63 at the time of the Armory Show), his ideas have some congruency with the avant garde in his pursuit of an artistic vision through the "innocent eye" of sense impressions and his admiration of non-western or "primitive" art. His love for the flat, essentially abstract patterns of Indian and Islamic art didn’t influence his paintings. As a decorator, however, his "sheer inventiveness" from the ornate flat surfaces of his carved panels and stencil designs to his use of rich colors to create interiors of extraordinary warmth and complexity link him to the development of Art Nouveau in America.

He was a thoughtful, innovative, creative personality whose travels and life style not only reveal a fascinating facet of American life at the turn of the century, but whose work deserves rediscovery and re-evaluation in the light of the new.

Submitted to the Docent Council by Gay Collins

Bibliography:

Exhibition Catalogs: Heckscher Museum, Huntington, N.Y., 1976

Lockwood De Forest, Painter, Importer, Decorator

Alaska State Museum, Juneau, Aug.24-Oct.2, 1988

Lockwood De Forest, Alaska Oil Sketches