Hung Liu

Chinese, 1948- (active America)

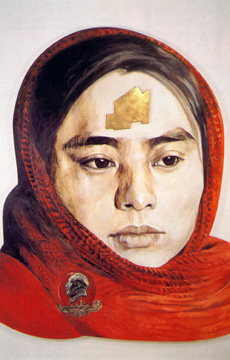

A Third World, 1993

oil on canvas, gold leaf on wood

92 x 76 x 3 in.

SBMA, Museum Purchase with funds provided by the 20th Century Art Acquisition Fund, and by Jill and John C. Bishop, Jr. and Lillian and Jon B. Lovelace

1993.29

RESEARCH PAPER

Hung Liu received her education in China and in the USA. In 1975 she received her degree in Fine Arts at Beijing Teachers’ College. In 1981 she received the equivalent of and MFA in Mural Painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. In 1986 she entered UC San Diego and received an MFA in Visual Arts.

Hung Liu’s work appeared in the 1993 exhibition “Backtalk” at The Contemporary Arts Forum in Santa Barbara.

To some extent Hung Liu has been in rebellion against her Communist heritage from the moment she chose to become an artist. Traditional China has regarded art as primarily the profession of men; women were largely excluded. In a more profound sense, her choice of art as a career was also courageous. Art, especially in authoritarian societies, has the potential of being subversive and therefore dangerous.

Landscapes, her preferred subject matter, show her connection to traditional Chinese painting, reflecting her pride in her ancient heritage.

Art in the People’s Republic of China became, under Chairman Mao, much like its counterpart in the USSR: illustration and propaganda glorifying the state and its leaders. Hung Liu’s art, in contrast, is about the rights of the individual. She is angry about the conditions in Chinese society in which she grew up, its authoritarianism and the consequent loss of personal identity and selfhood it demands. The Old China was a master/slave society. In Communist China, where the state has the right to terminate the individual, the master/slave relationship continues.

In such a repressive society, intellectuals and artists are, by definition, rebels. Hung Liu was both an intellectual and an artist, reason enough for the government to feel that she was in need of rehabilitation. She was sent to live on a collective farm. Life on the collective brought the young artist into contact with the peasants for the first time. She developed sympathy, and more importantly, empathy for the Chinese peasantry. Attitudes developed there were to become influential to her art.

Hung Liu portrays the women of Old China in her studies of Chinese prostitutes. Working from photographs in turn-of-the-century catalogues of famous prostitutes posed with symbolic objects and often with their bound feet showing beneath their garments, she presents us with a gallery of Eastern Odalisques who gaze directly at us in the manner of Manet’s Olympia. In contrast to these prostitutes, whose bound feet are the quintessential symbol of female oppression, Hung Liu also shows the modern Chinese woman, asexual in their uniforms, anonymous functionaries in a repressive society.

A Third World is a self-portrait using brilliant color red of the encircling scarf to enhance the drama of its monumental size. Tremendous portraits of Chairman Mao, we recall, dominated every square, every building in China. Hung Liu seems to be asserting her importance as an individual as she constructs her portrait in an equally grandiose manner.

In A Third World, Mao is no longer on Hung Liu’s mind. What is on her mind, shown literally on her forehead, is a map of San Francisco from 1839. This is the first known map of San Francisco, and Donald Kuspit thinks Hung Liu may have chosen it as representative of an idealized time and place. Kuspit goes to some lengths to point out that this gold medallion is not a caste mark; it is a symbol of her new world. The map itself is a wooden attachment covered in gold leaf. It may also reference the fact that when the Chinese first came to California, they referred to San Francisco as Gold Mountain.

Hung Liu’s head is covered—a symbol of submission in many cultures, but also a reflection of the headwear of new immigrants to this country. Pinned to the shawl there is a large button showing Chairman Mao in gold profile. The red of her shawl and the Mao button tell of her origins and experiences. The portrait itself resonates as a monumental passport photograph.

The canvas is shaped to conform to the outline of her self-portrait. The shaped canvas increases the drama of her work; she uses this technique in other monumental portraits, asserting the worth and value to society of these ordinary subjects.

One becomes alive in a totalitarian society through anger. Hung Liu has chosen to show us yet another way: through art. Having learned about the worth of the individual through her own struggles to become an artist, and having come to respect the rights of peasant farmers and their work, she has arrived in this country prepared to show us that the struggle for human rights and freedoms still exists here for those who belong to A Third World.