Percy Wyndham Lewis

British, 1882-1957

Red and Black Principle, 1936

oil on canvas

46 × 24 in.

SBMA, Gift of Wright S. Ludington

1956.2.1

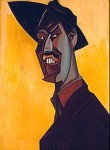

Wyndham Lewis, Self-Portrait, 1921

RESEARCH PAPER

Percy Wyndham Lewis was probably--Caligula aside--the most unpleasant person who ever lived. But he was also a superb draftsman, an interesting painter in oils and played an important role in 20th century art as the inventor, spokesman and leading figure of the Vorticist Movement in England immediately before World War I.

Three of his works that the Museum owns were gifts of Wright Ludington:

Portrait of Ezra Pound (charcoal and grease pencil on smooth paper)

Portrait of Olivia Shakespear (black pencil on plate paper)

Red and Black Principle (oil on canvas)

The two drawings are the earlier works: the Olivia Shakespear is signed and dated 1920, and the Ezra Pound, while neither signed nor dated, bears a strong resemblance to other sketches Lewis drew of his friend during 1919 and 1920. Both works show the remarkable sureness and strength of Lewis' control of line.

the Portrait of Olivia Shakespear is a full lensth figure of a well-dressed, mature woman seated in a chair. The features are strong, especially the jaw, the neck is sturdy, and the eyes are cold. Although the pose is relaxed, she is seated on the edge of the chair, as if impatient to be up and doing. Lewis' bold, heavy lines across the sholders and outlining the bell curve of the skirt convey the feeling of energy only momentarily forced into inaction. The feet, modishly shod in what appear to be spats, are particularly delightful in their quicker curves and apostrophe-suggested buttons. Olivia, incidentally, was Lewis' mother-in-law.

The Portrait of Ezra Pound is one of many Lewis drew and painted of his close friend, the well known American poet. Pound is credited with suggesting the name for Lewis' new concept of art -- Vorticism.) Our drawing, shows only Pound's head, half-way between a profile and three-quarter position and viewed from above, so that all of the lines starting at the back of the head converge at the tip of the goatee. Again, the face is strong, stern, and cold. The edges of the mouth turn down severely, the forehead bulges with creative thoughts and the pince-nez, rather than suggesting anything comic or age-weakened, adds to the severity.

The Red and Black Principle might have been painted by a different artist, although its strength is in line rather than color. It shows two standing figures dressed an what might be armor reminiscent of Roman legions. The heads are simplified -- only bold white planes suggest frontal bones and noses. Eyes are simple empty circles. There is no hair. Are these space helmets? There are suggestions that the figure on the viewers right is female: circles that might be breasts, a narrow torso and more slender legs - although this figure is taller of the two.

Such figures appear in many of Lewis' paintings. They are not human, rather, beings from another world. Lewis says: "I had . . . the desire to project a race of visually logical beings . . . If I had given them a name it would probably have been monads." But they are not frightening in not being human. On the contrary, they seem reserved, innocent and even vulnerable. They are, perhaps, how man might evolve if the Mechanical Age reaches maturity.

Lewis was intrigued with machines and the qualities of the metals with which they were constructed. He says: "I considered the world of machinery as real to us, or more so, than nature's forms, such as trees, leaves, and so forth, and that machine-forms had an equal right to exist on our canvases." Some of his best-known paintings are of World War I gun emplacements, where the giant cannons are the heros and the soldiers merely peripheral attendants. Even his colors are metallic rather than organic--the greys are steely, the whites announce themselves as "leadwhite," while the reds (as in our paintinc) look as though they might have been compounded of rust scraped from metal long exposed to the elements and mixed with motor oil.

Lewis, as one biographer put it, combined "persecution mania and overriding egotism." He also seems to have been a poseur and probably a liar about his origins. For a long time the only thing he would reveal was the year of his birth, 1884. Later, he claimed to have been born aboard his British parents' yacht anchored off the coast of Nova Scotia. He also claimed to have been at Rugby during 1897 and 1898, but no one there in those years could be found to remember him. It has been verified, though, that he attended the Slade School of Art in London from 1898 to 1901 and spent the next eight years travelling around Europe. He began to paint again only on his return to London where he had work shown in several exhibitions.

In 1913 Lewis and art critic Roger Fry established the Omega Workshops where artists and craftsmen were to work together at coordinated, furniture and interior design. The concept, based on William Morris arts and crafts movement, was modified by Lewis and Fry to incorporate new industrial techniques. In less than a year a bitter quarrel broke out between the two founders (Fry had subverted a commission intended for Lewis personally into a workshop-wide project in which Lewis had only a minor role.) Within a few months Lewis found a sponsor and opened his own Rebel Art Centre. His paranoia, which led him to lock his own paintings in a small back room to save them from would-be plagiarists, worked against the Centre's communal spirit. His sponsor grew, weary of Lewis' bad manners and the Centre shortly dissolved. Lewis was invariably rude to people from whom he obtained money: once, when an installment of a "fund" set up to help him failed to arrive, he gent the administratrix a postcard reading simply, "Where's the fucking stipeud?"

Oddly enough, Lewis wrote more than he painted and is probably as well or better know for his novels and essys than for his graphic art. In 1914 he published the first issue of a periodical, Blast No. 1: Review of the Great English Vortex , intended to be a verbal expression of the Vorticist Movement in the visual arts. It awarded "blasts" and "blessings" to aspects of contemporary British life, especially in the arts. The periodical's slant life ended with the publication of Blast No. 2 just before the outbreak of World War I. Lewis' writing is largely verbal attacks, often witty on society, proponents of non Vorticist art movements, benefactors, fellow, artists and friends. One laughs, but is left with a bad taste in one's mouth.

More than one scholar and art critic faults Lewis for inconsistency and obscurity in his statement of the Vorticist theory of art. By piecing together the words of Lewis and others we seem to come up with the following surmmarv of the Vorticist ethic: "deadness is the first condition of art." ".........a sort of death and silence in the middle of life . . . (is the painter's) immortality." "The still center at the heart of life, of contempory flux, is Vortex, a principle of unity and permanence in the maelstrom of life's diversity and change." "You think . . . of a whirlpool. At the heart . . . is a great silent place where all energy is concentrated. And there, at the point of concentration, is the Vorticist."

Even now it is impossible to state with any surity exactly what it was. "We are given by the eye too much: a surfeit of information and 'hard fact' . .' it (Vorticism) was dogmatically anti-real. . . . the idea was to build up a visual language as abstract as music." Art critic Richard Cork finds a further contradiction in that the visual image suggested by a vortex (or whirlpool) is not expressed by the rigid, angular and diagonally oriented Vorticist compositions. Later, in the introduction to the Tate Gallery's catalog for the 1956 exhibition, "Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism," Lewis himself states:

"About the Group, directed by myself, and called "Vorticist," a great deal has been written by what we now call Art Historians. Some . . . has been unrecognizable. Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did, and said, at a certain period."

The statement was not particulary appreciated by his former friends and collegues. It is very probable that the importance accredited in art history to Vorticism was due more to Lewis' writings than the visual creations that came out of it.

Toward the end of his life at 73 Lewis became blind. Neither affliction nor age softened his tongue or pen. He remained a witty, vicious, ungraeful, pompous proponent of his own erratic views of art and the world at large.

Lewis, Wyndham. Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism ., Introduction. Tate Gallery, 195_.

Cork, Richard. Vorticism and It's Allies . Arts Council, 1974

Synims, Julian. Introduction, Wyndham Lewis in Canada, p.2.

Lewis, Wyndham. Tarr (1918 edition revised). London, Chatto and Windus, 1928, p. 302.

"Credentials of a Painter". The English Review , Vol. XXIV (January 1922), p. 36.

Wagner, Geoffrey. "Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticist Aesthetics," Journal of Aesthetics and Arts Criticism , Vol. XIII, No. 1, September, 1954. (reprint, p. _)

Hunt, Violet. I Have This to Say . New York, 1926, p. 215. (As the author quotes Lewis speaking in 1914.)

Bibliography on file SBMA Docent Council.

Transcribed by Loree Gold from SBMA Docent files, 2008, no name or date given on original paper.

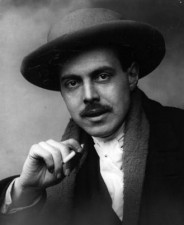

Undated photograph of Wyndham Lewis

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Lewis was a painter, writer and polemicist; his background gives some clue to the restlessness and pugnacity that was to mark much of his life. He was born on a yacht off Amherst, Nova Scotia, the son of a British mother and American father who had fought on the Unionist side in the Civil War and been captured by the Confederate Army at the Battle of Wilderness. The family moved to England in 1888 where the father abandoned them five years later. Lewis studied at the Slade School and later at the Académie Julian in Paris. He was a natural rebel; he quickly allied himself with the Italian Futurist painter Marinetti and the Rebel Art Centre in London, publishing the Vorticist manifesto BLAST in 1914. A number of his works of the mid 1930s reflect concerns related to the Spanish Civil War during which, like his friend Ezra Pound, he was a firm supporter of General Franco’s regime.

British Modernism Whistler to WWII

2016