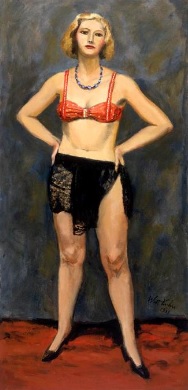

Walt Kuhn

American, 1880-1949

Trude, 1931

oil on canvas

68 x 33 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Walt Kuhn in memory of Walt Kuhn

1954.12

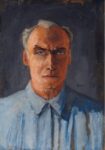

Walt Kuhn - Self-Portrait, 1942

"If I can leave at least one fine painting, I will be content. " - Walt Kuhn

RESEARCH PAPER

“Trude”, an oil on canvas painting, was a gift to the museum by Mrs. Kuhn in memory of her husband. Like Manet, Kuhn places his figure parallel to the canvas surface without employing techniques such as foreshortening or conspicuous modeling. The resulting composition is a flat-appearing one, bold and frontal in its effect. Executed in forthright projection against a murky background, “Trude” is typical of Kuhn's cool and clear color-scheme with heavy use of blues, grays and browns which seem to spring from the subject itself. Just as typical is the almost brutal accent of the red brassiere and the less dramatic treatment of the blue beads which lend vibrating life to the picture. The strong linear impact of the arms akimbo balances nicely with the slight diagonals of the legs astride dark triangular negative space to which the eye is led via the black drapery hanging carelessly from the waist. The oval of the face seems "floated" in an unnatural attitude against the dark shadow of her hair, and the chalky, theatrical makeup suggests the mystical and melancholy. No background, no "environmental irrelevancy", is allowed to distract from or to diminish the compelling force of Kuhn's heroic female, whom he considered his first wholly successful showgirl: "Blond, clean, and striking a powerful stance, proud Trude remains, as either principal or chorine, ever victorious."

A tireless, self-demanding artist, Kuhn felt that for him a painting had to be as self-sufficient an entity as any other fact of nature; or to draw from his favorite repertory of symbols, show business, a painting should seem as effortless and inevitable as a tightrope act wherein the performer occasionally pretends to lose his balance just to show how difficult, even dangerous, it really is. In other words, a painting should draw a cloak of surface finish over the bare bones and muscles of its structure.

Walt Kuhn was born in Brooklyn in 1877 of naturalized American parents, the father Bavarian and the mother half Spanish and half German. It was she who imbued in her son a deep love of the theater and it is felt that the Spanish strain in Kuhn's background was responsible for the dignity and gravity of his compositions and also for the somewhat limited range of his palette. After early schooling and with no desire to enter college, he started a bicycle shop in uptown Brooklyn. Summers he spent barnstorming county fairs as a professional bicycle racer, and it was then he first encountered the people of the sideshow and of the entertainment world. After two years, in 1899, he moved on to San Francisco where, untutored and untrained, he started drawing cartoons for The Wasp and other newspapers. Roving the West Coast and adventuring in the Sierras he registered the many impressions received there, and these were to remain with him all his life. Many years later there developed out of these memorabilia a series of 29 oils painted from 1918 to 1923 and entitled: "An Imaginary History of the West." He felt that in the West he had encountered "a basic American, unmachined, tough to the point of hardness, independent, masculine, but not incapable of feeling.

With this spate of ideas, but with a need for formal training, he followed the course of most fledgling artists to Paris, arriving there in 1901, but he stayed less than a year. Munich was more to his liking, and it was there he learned not only the academics of art but the very important lesson of the brevity of time. Having shown his opus number one to his instructor, Heinrich von Zugell, he received favorable criticism, but when asked by his teacher where the others were, he replied that there were no others - there would be plenty of time later in the summer. "Time!", retorted von Zugell, "With your puny talent do you know what time it is? It's a quarter to 12!"

He returned to New York City where, from 1905 he taught himself drawing at the Artists‘ Sketch Class. Realizing that a painter must know the whole vocabulary of art, he studied Greek sculpture and Chinese painting and examined all styles and periods, judging his own work against the severest standards of the past. He belonged to an era that introduced Modern Art to America and was not only a revolutions painter who had experimented with collage, Cubism, and Expressionism, but an artist of rare refinement. A fiercely independent person who never entered his works in competition, Kuhn belonged to no "school", but did help organize the Armory Show of 1913, a collection of 1090 works by American and European artists, and undoubtedly the most important exhibition ever held in this country. Ruthless in self-appraisal, he destroyed probably half of his paintings throughout his career, arguing that "they didn't age well." When a canvas was finished he would roll it up and store it in a rack. After a year or so he would pull out the canvas and take another look, and if it wasn't able to take this kind of treatment, it wasn't well painted and wouldn't last anyway, according to its creator.

Early in his career he pursued the use of metaphor, the power of the particular to reveal the general - the painter's basic tool of expression. "All art is metaphor," he often said. "You don't get anywhere telling a girl she has a neck like a neck. You tell her she has a neck like a swan. You still may not get anywhere, but at least you've tried." In 1925, after a near-fatal bout with a stomach ulcer, it was, indeed, almost "a quarter to 12". It was then Kuhn realized that he had not one fully achieved, absolute painting to leave to posterity. With the sanction of his wife, Vera, a jewelry designer, and of his daughter, Brenda, he decided to drop everything for two years and to pour out all that he had lived and learned on canvas, and out came the metaphors: showgirls, acrobats, clowns, symbols not of mere entertainment but charged with profound human meaning.

The acrobat is a product of lifetime discipline. The clown is conventionally tragic, or at least a pathetic symbol, brokenhearted under the coverup of gaiety; but serious training and highly stylized pantomime go into professional clowning. The show girl behind her mask of makeup is capable of demonstrating the nobility of survival over the "insolence of circumstance." It was in 1931, during the height of his productivity, that our “Trude”, the first in the succession of show girls, was painted. Though I could find no information on who the model might have been, I did discover that a watercolor similar to the oil was done earlier that year. By this time the artist had achieved his first goal, that of the unadorned direct statement, almost blunt in its finality and achieved by working for the larger purpose, never "painting for the sake of painting." He had too much to say to bother turning out merely attractive pieces of art. Late in the '30s he broadened his scope by serving as consulting architect for the Union Pacific Railroad. The '40s brought new authority to his work, and a subtle change in his characters reflects more psychological penetration and less of the abstract quality of his earlier works.

The painting "Roberto", when it was shown in I946, brought one of the highest prices ever paid for a living American's work. In 1948 during the course of his last exhibition, Fifty Years a Painter, there was evidence that his previous eccentricities with which he had jealously guarded his independence had gradually been exaggerated into outright hostility. His last months were spent in a mental sanatorium, where he died of a perforated ulcer on July 13, 1949.

In way of a personal note, I should like to add that Joseph Goethe, a neighbor and artist, knew Walt Kuhn in Washington D.C. during the early '30s, when he would visit the Phillips Gallery where Mr. Goethe was a struggling young art student. Of all the professional people he has known, Walt Kuhn stands out above all the rest as a help and an inspiration. "He was a quiet, unassuming man - very nice."

Prepared for the Docent Council of SBMA by Corinne Underwood, n.d.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams , Philip Rhys. "Walt Kuhn. Drawings and Watercolors by Walt Kuhn." Kennedy Galleries; 1968.

Adams, Philip Rhys. "Walt Kuhn--A Memorial Exhibition. An Introduction to the Artist." (catalog) Cincinnati Art Museum; 1960.

Adams, Philip Rhys. "Walt Kuhn, Painter of Vision." (catalog) Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona Art Gallery, 1966.

Bartlett, Fred S. "Walt Kuhn, An Imaginary History of the West." (catalog) Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 1964.

Bird, Paul. Obituary. Art Digest, (August 1949), p. 13.

Freund, Frank E. Washburn. "Walt Kuhn," Creative Art, (May 1932) pp. 347-349.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

By 1931 when Walk Kuhn painted this work, the large-scale, full-length society portrait was a well-established form in American art. Here, Kuhn has given that tradition an interesting modern twist. His subject, a chorus girl named Gertrude Lower who was performing with a road company in the musical Show Boat, is as bold and unapologetic as the upper-class ladies who normally posed for this type of portrait. Though her weight is shifted slightly to one leg, in another nod to artistic tradition, her feet are placed far enough apart so that she is completely stable, even in her high-heeled black shoes. She has her arms akimbo, with her hands planted firmly on her hips. By seeing her posed and dressed this way, the viewer takes on the disquieting role of voyeur.

Yet despite her pose and revealing costume, Trude actually is far less seductive than many of the women in society portraits of the time. Her mismatched outfit appears to have been assembled hastily from items at hand. She boldly confronts the viewer with her body, but gazes down and away from the immediate space, suggesting that she is neither fully available nor particularly interested in our attention. Her blank expression reveals nothing. Kuhn has made no attempt either to romanticize or pass judgment on her life. This ambiguity invites us to draw our own conclusions about her and her place in modern society.

SBMA INFORM #1745, 1/22/98