Leon Kossoff

British, 1926-

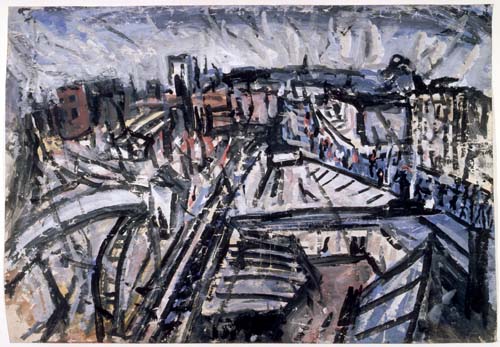

Dalston Junction with Ridley Road Street Market, 1972

gouache on paper

30 1/8 x 43 1/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Margaret P. Mallory

1991.154.19

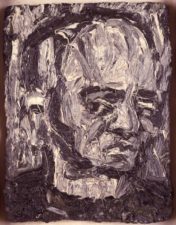

Kossoff in his studio by Bob Collins, bromide fibre print, 1972

“Ever since the age of twelve, I have drawn and painted London...the strange ever-changing light, the endless streets and the shuddering feel of the sprawling city linger in my mind like a faintly glimmering memory of a long-forgotten, perhaps never experienced childhood, which, if rediscovered and illuminated, would ameliorate the pain of the present.”

- Leon Kossoff, Recent Paintings and Drawings (Fischer Fine Art, London, 1972)

Kossoff self-portrait, oil on board, 1981

COMMENTS

Leon Kossoff was born in east London. He studied at Saint Martin’s (where he and Frank Auerbach became close friends), at Borough Polytechnic, and at the Royal College of Art. He had his first exhibition at London’s Beaux Arts Gallery in 1957. From the early 1950s Kossoff began painting a close circle of family and friends, producing pictures in which they acquired a solid, material presence, similar to that of the buildings and streets of London he also often returned to and knew intimately.

He developed a painterly style with thickly applied, constantly reworked layers of paint in characteristic earth colors. Early drawings were intensively worked as he repeatedly erased and restarted the image. He was to develop a similar process in his paintings, working on board and scraping down the paint with a palette knife before reapplying it. Kossoff lives and works in north London.

“Every time the model sits everything has changed. You have changed, the light has changed, the balance has changed.”

- Leon Kossoff, Recent Paintings, Edinburgh Scottish Academy, 1987

Last summer, during the Olympics, the painter Leon Kossoff found himself back in the East End of London, in Arnold Circus in Shoreditch. "It was a miracle," he says – and then with typical self-effacement takes the word back. "No: that's an exaggeration. Anyway, it was the summer of the Olympics. There wasn't much traffic. I didn't approve of how they changed things, to build the park, but I did enjoy it. Everything seemed different, people seemed happy … Returning to Arnold Circus wasn't something I anticipated. I just went down there one day and I had to draw it."

He made drawing after drawing of the pinkish red-brick buildings (Britain's first housing estate, built in the 1890s) that surround the little park in the circus, with its bandstand at the centre. Summer trees jostle against a hot blue sky. In the distance, the tower of Hawksmoor's Christ Church, Spitalfields rises up with its customary effrontery – it is a building that he drew and painted repeatedly in the 1980s and 90s. The drawings of Arnold Circus are sunny, full of heat and light and even contentment. (Rather extraordinary for an artist of whom it was once written: "He provides so much unrestricted access to such massive amounts of spiritual discomfort that you marvel at its starkness.") A cyclist whizzes through one drawing; a mother sits on a bench in another. The last one he made is inscribed "Saturday afternoon" in a shaky hand at its base, and he eyes it with tentative, and, he leads me to believe, wholly uncharacteristic satisfaction. Had you been wandering through Arnold Circus that afternoon during the Olympics it seems to me unlikely you would have noticed this slight, elderly, even Pooterish figure with his drawing board, in his bearing and manner the very definition of unassuming.

Kossoff is now 86 years old, born a few months after Lady Thatcher (we meet at his gallery, Annely Juda Fine Art, as her funeral is under way at the other end of central London). Arnold Circus was one of his childhood stamping grounds: as a boy he attended the Rochelle School there, which is now converted into studios, the offices of Frieze magazine, and an arty canteen. His father, a first-generation immigrant from Ukraine, owned a bakery round the corner in Calvert Road; he was one of seven siblings. It was "absolutely not", he says, an artistic household. "Painting didn't exist in my family." What drew him to art as a boy was finding himself, almost without knowing how he had got there, in the National Gallery. "At first the pictures were frightening for me – the first rooms were hung with religious paintings whose subjects were unfamiliar to me." Later they became old friends: Kossoff spent a long period visiting the National Gallery before opening hours, working from the old masters, making not copies but what you might call translations.

Aside from these works from old masters, and his many paintings and drawings of human subjects, London has always been Kossoff's most important subject. It is these London landscapes, from a sombre charcoal from 1952 of the railway bridge at Mornington Crescent, to the Arnold Circus drawings that he made 60 years later, that are the basis of his latest exhibition.

There are 10 paintings in the show, but mostly it is about the drawings: fruits of his daily practice of putting charcoal to paper to try to make sense of the world. In a published correspondence in the New Yorker with the critic and novelist John Berger – just a few pages long, but the nearest Kossoff has ever come to expansive self-explanation – he wrote: "The main thing that has kept me going all these years is my obsession that I need to teach myself to draw. I have never felt that I can draw and as time has passed this feeling has not changed. So my work has been an experiment in self-education." He still feels the same, he says, as we wander among his works. "I don't seem to be able to do a drawing," he says, mournfully. "I've never felt … oh, never mind." To call this gentle and modest man reticent about his work would be to understate the case (this is the nearest he has ever got to what you might call giving an interview, though he insists that we are merely conversing). Eventually, he concedes: "I suppose I feel I might have done a few drawings."

Kossoff has lived nearly all his life in London. The only exceptions were two years spent in King's Lynn as an evacuee – rural Norfolk coming as a shock after the East End – and then when he joined up, aged 18 and, via the Royal Fusiliers, joined the Jewish Brigade, serving in Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands. Before his war service, he started attending life-drawing classes at Toynbee Hall, the pioneering East End charity. "That really stunned me," he says. "Seeing someone posing, and people drawing – they all seemed then to be as good as Degas to me." He went on to study at St Martin's, but the most formative training was with David Bomberg at the Borough Polytechnic, before he established a studio at Mornington Crescent, north of Euston station.

London was, of course, in a state of destruction after the second world war. A huge swathe of the City, from where the Barbican now stands and east of St Paul's down to the Thames, was completely wiped out. Familiar streets were rendered unrecognisable, buildings turned into cliffs of rubble. New vistas were created where once buildings had crowded together. It was a landscape of appalling ruination – "awful but also rather beautiful", he says, a new territory waiting to be discovered. An early subject is a building site at St Paul's, the cathedral not so much reaching up to proclaim itself as a symbol of British resourcefulness and triumph, but a doomy black dome in the background of a thickly drawn ensemble of grey rectangles and triangles.

The pattern of Kossoff's work has been to pursue, sometimes obsessively, a single subject over a period of years. On the mornings he did not have a sitter arriving in the studio, he would set off early to a chosen spot with his drawing board to work out of doors; then he would return to the studio to paint – a laborious process through which the final image would emerge only after many months of applying and then scraping away paint.

It seems that Kossoff has frequently been drawn to landscapes that suggest a state of transition: either because they are undergoing literal change, such as the St Paul's building site; or because they are, like tube stations or railway lines, the zone of humans on the move. Christ Church, Spitalfields, which he painted for years, its facade looming monumentally, and miraculously (in his paintings at least) failing to topple despite itself, is a rare example of something that might be regarded as a "view" in the conventional sense.

Kossoff's territory is, more frequently, the overlooked: the railway siding; the demolition site; the Victorian school building seen from across a busy road; the underground station. These views present themselves to him with a kind of inevitability. "It is a question of the eye and the mind," he says. They are the kind of landscapes that many people would hesitate to regard as "scenic", but that carry their own rough loveliness. "Perhaps everything's beautiful," he says. "It's a question of how you experience things visually." He adds: "Something happens when you see Willesden Junction stretching out in front of you. What else can you do but draw it?"

He worked for years drawing and painting Kilburn tube station. Eventually the faces in the crowd turned unbidden into the faces of people he knew as he painted. He points out to me the face of his father, and that of his wife. Seeing the drawings in the gallery, rather than simply in reproduction, they suddenly seem busier, more clamorous, less bleak. In the early 1970s, he used to take his son to the public baths in Willesden, and depicted the full pool, joyous and splashing and teeming – some of his best works. They are pictures, as he says simply, of "life going on".

When I ask Kossoff why he believes he was drawn to making art, he shakes his head, but then says, "I think it may be because I used to enjoy looking out of the window as a boy." Many of his drawings have been made by looking out of a studio window: finding the beauty of what's there, right in front of him. The works in the exhibition function as a kind of map of Kossoff's memory and sightlines, his peregrinations over a period of many years, from Bethnal Green in the East End to Mornington Crescent, north of Euston, from Dalston in Hackney to Willesden in the north-west of the city. In the early 1970s he had a studio at Dalston, and drew what lay outside.

"This gouache is all right," he says grudgingly of one such work. Or else he would venture into the streets, drawing, for example, the nearby German hospital built for immigrants in the 1840s, where, he informs me, Joseph Conrad was once admitted. The family home has been for decades in Willesden; at the bottom of the garden is a railway line from which, in the 1980s and 1990s, he'd draw the locomotives dashing through. Train lines, he says, "open out the landscape, somehow". A recent subject has been a cherry tree in his garden, one of its lolling branches steadied with struts: once, before the suburban houses were built, there was an orchard here. Many of the landscapes in his drawings and paintings are now gone, which is why to look at them is to look through Kossoff's eyes but also to travel into his past with him. Even the trains at the bottom of the garden look different now, he tells me: trees have grown up to obscure the view.

Those who pass through King's Cross on their daily commute or on visits to London are witnessing it now changing day by day, as new buildings are growing up, and old sights quickly disappearing. Kossoff came here repeatedly, drawing St Pancras before the Eurostar terminal was opened, and the Victorian gasometers that lie behind it, and the hubbub of commuters outside King's Cross station: to draw Lewis Cubitt's great sheds, he used to stand inconspicuously at the top of a set of steps that led up to St Pancras between the two stations. He drew, too, the grand staircase at the Midland Hotel in 2005 – then a scene of gracious dereliction, now smartened beyond recognition.

Kossoff says that he cannot paint any more. The physical exertion is too much. Nor, he says, is he inclined to go out into the world with his drawing board, though he is still drawing from sitters in his studio. Several years ago, he tells me, he abandoned listening to Beethoven and Shostakovich quartets as he worked, in favour of Bach and Schubert. Now, though, he has gone back to the late Beethovens. At the Rochelle School, they've kept a drawing board of his, and some materials, which he was allowed to store there to save his lugging them to and from Willesden every day as he drew there last summer. "They are there for me whenever I want to go back," he says.

- Charlotte Higgins, The Guardian, April 06, 2013

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Born in London of Russian Jewish parents, Kossoff studied at St Martin’s School of Art and later with David Bomberg at Borough Polytechnic alongside Frank Auerbach. Both artists were obsessed by London’s urban landscape and used heavy impasto in their works.

- British Modernism From Whistler to WWII, 2016