Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

German, 1880-1938

Davos, 1924

oil on canvas

16 x 20 in.

SBMA, Gift of Margaret P. Mallory

1991.154.16

Photograph of Ernst Kirchner as a young man in Bavaria

RESEARCH PAPER

Identity and Description of Object

"Davos" was painted in 1924 by German artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. The subject is a view around Davos, a small mountain village in the Swiss Alps. Unlike his earlier works, which show agitated, vehement, and brutal expressionism that seemed to tear his canvases apart, Davos' emotive qualities are more passionate and poetic, more restful and resigned.

Style

Ernst Ludwig Kircher was born at Aschaffenbury, in Franconia, to a well-to-do, middle-class family, and was reared in Chemnitz in Saxony. He showed a strong interest in drawing by the time he was three years old. While still in high school, Kirchner was given wood blocks by his Father, from which he made woodcuts of his own drawings. The technique learned from this medium--simplification, elimination, and overlapping, the very nature of the woodcarving technique--remained a distinctive characteristic of his work throughout his life. His drawings from this early period were energetic sketches in which he recorded immediate visual impressions, and his chaotic strokes were already showing emotional energy.

He left his architectural studies in Dresden in 1903, and began to study painting seriously in Munich. From the start, he wanted his art to be a vital image of life and to capture the realities of its surroundings. A form of social realism had taken hold not only in Germany, nor in Europe alone, but in a place as remote as America. By 1904, Kirchner became associated with three other young architectural students: Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Leaving their architectural studies behind them, they formed & group called Die Brücke, meaning The Bridge. Repelled by the lack of passion in the art they saw around them, the group felt a need to search for an intuitive form of expression, which they thought lay somewhere between imaginative and descriptive art. The result was an explosion of expressive works. Exaggerations and distortions became a means by which they interjected themselves into their paintings. Intensity of color, simplification of form, and surrounding the color surface with a heavy dark line all enhanced the movement of line. Oriental prints with boldly simplified decorative color and primitive African art also had an influence on their work. The work of the Post-Impressionists Van Gogh and Gauguin also influenced their work, as did the Fauves, especially Matisse. The end goal of these stylistic movements was the same--to break with the stubborn, persistent Impressionist style.

Impressionism arrived in Germany almost a generation later than it did in France, and by the time it arrived there it had already come under fire in France. It became identified with materialism and was a target of not only the realist movement in painting but also with the social and political movements taking place worldwide. The Germans were never fully able to feel comfortable with the radiantly beautiful facade of nature as painted by the Impressionists. Instead, they recognized nature as often hostile and cruel in reality, unconcerned with man, who had to fight it alone and was threatened by demons, real and unreal. Van Gogh's work, for example, spawned a new generation of artists who probed more deeply into the nature of things. Visible appearance became less important than the relationship between man and the object. This shift of attitude was basically what changed the tide from Impressionism to Expressionism.

In 1912, Kirchner left Die Brücke, and went on his own to Berlin, where he found more appropriate subject matter for his personal technique--the pace and the glare, and the evils of the big city. The city's jungle-like character was frightening and man was a victim--a puppet-like object. Kirchner's approach was direct and shocking, frightening the spectator into awareness. His Berlin scenes from this period mark the high point of Kirchner's career, and represent the most extreme Brücke German Expressionist style.

Content

"Davos" was painted during the period of time in which Kirchner lived in Davos, Switzerland. He came to Davos in 1917, desperately ill. Recently discharged from the German army, he was broken in spirit, disillusioned, and severely handicapped psychologically. His ties with his friends, family, and homeland were broken. He was a man alone, trying to recover both his physical and mental health. Communication with nature in this small mountain village in the Alps appears to have been instrumental in the clarification of Kirchner's disturbed inner world. The awesome grandeur of the mountains and the strength of the mountain people enabled him to come to terms with his new reality.

We see in this work Kirchner's expressive use of strong, clear colors, simple forms, and large flat areas, reminiscent of his earlier works. His compositional structure is tight and well disciplined--the verticals and horizontals are dynamic, and space, which is organized with superimposed planes, achieves a sense of perspective despite its two-dimensionality. It is clearly the work of the pre-war Kirchner, but the spirit and energy is gone.

During his 21 years in Davos, he hoped to see German art return from its neglect during the war, but representational art as Kirchner knew it never developed beyond or even returned to the spirit, fire, and enthusiasm it had held during the height of the Brücke movement. The humanitarianism of Expressionism slipped into cynicism, brought about by war and revolution, and bitter disillusionment, as witnessed by the art of Otto Dix and George Grosz. Art had taken a new direction in an attempt to fill the needs of postwar society.

Kirchner committed suicide on June 15, 1938, soon after much of his work was seized, ridiculed, and destroyed by the Nazis when Hitler came to power.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Elsa L. Mayor, April 11, 1986

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Chipp, Herschel B. Theories of Modern Art. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1968.

Haftmann, Werner. Painting in the Twentieth Century. New York and Washington: Praeger Publishers, 1965.

Selz, Peter. German Expressionist Painting. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1957.

Willett, John. Art and Politics in the Weimar Period: 1917-1933. New York, New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Files

Art Conservation Laboratories of Santa Barbara, Inc. Restoration Report, June 10, 1985.

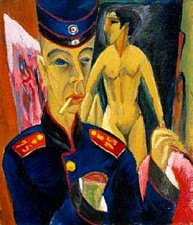

Painted in 1915, Kirchner's Self-Portrait as a Soldier documents the artist's fear that the war would destroy his creative powers and in a broader sense symbolizes the reactions of the artists of his generation who suffered the kind of physical and mental damage Kirchner envisaged in this painting.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Kirchner was a founding member of “Die Brücke,” a group f self-taught artists determined to break with traditional forms of visual representation to found a more immediately emotional kind of art. The group’s establishment in 1905 is now recognized as the beginning of German Expressionism. Kirchner would go on to a career in Berlin, using the urban streetwalker in his paintings and prints as a metaphor for the city’s greed-driven industrialism. Upon the outbreak of World War I, Kirchner volunteered for service, but suffered a mental and physical collapse that led to his discharge. After treatment in a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, he remained in the area, depicting the local scenery as seen in this verdant mountainscape that seems to burst with sunlight. In 1937, Kirchner’s works were included in the notorious “Degenerate Art” exhibition, staged by the Nazis. Sadly, he committed suicide the following year.

- 20th Century European Art, 2021