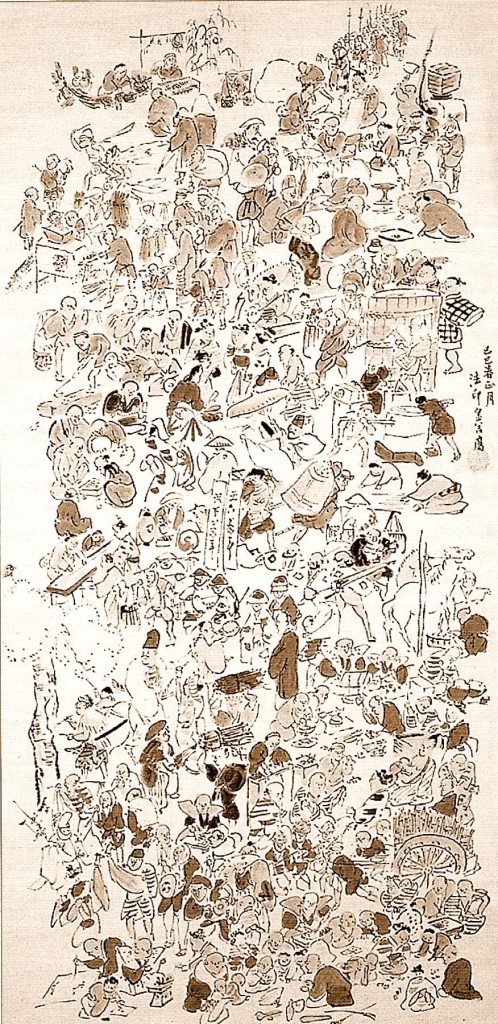

Yokoi Kinkoku

Japanese, 1761-1832

Peace and Prosperity Under Heaven, 1809

ink and light colors on paper, hanging scroll

53 x 26 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Wallis Foundation

1999.16

RESEARCH PAPER

How does one depict 188 figures within 58 1/8 x 26 inches without mass confusion or loss of each subject’s individuality? Yokoi Kinkoku used the compact format of the hanging scroll to express the seemingly commonplace with simple forms written in sketchy, spontaneous, energetic and fluid brushstrokes based on Nanga and Haiga paintings styles.

The story of his life shows how, experience by experience, he became a master Haiga painter. His life was like the mountain landscapes for which he became known. In his early years as a Buddhist monk and priest, his behavior alternated between devout and irreverent. His antics justly caused him to be known as "a breaker of all commandments". He spent several years as chief priest of a temple near Mount Kinkoku, from which he took his artistic name. Inappropriate behavior, the least of which was flying kites from the temple roof, and spending temple funds unwisely led to a mutual parting of priest and temple when the temple burnt to the ground in 1788. For the next twenty years he traveled and studied. He taught reading and calligraphy and painted didactic teaching materials for various temples in exchange for room and board and travel funds. His wanderings took him to the hot springs town of Kinosake, where he was exposed to the Japanese literati.

In China the literati belonged to the bureaucracy where positions came were won by the successful passing highly competitive exams based on knowledge of the Confucian Classics. The hereditary nature of official position in Japan verses one’s knowledge of the Classics resulted in the Japanese literati being a less homogeneous group. They could be scholars, poets or painters, doctors, merchants or even farmers who valued the arts and wished to communicated with others of like mind.

Eventually Kinkoku settled in Nagoya, through which people from all walks of life passed on their way to and from Kyoto and Edo. This traffic stimulated commerce and the arts. It was here that Kinkoku was exposed to the wholly Japanese Haiga painting style that was to have a lasting effect on his work. This was the time of the Tokugawa Shoganate, a time of economic strength, stability and peace. The educated had the time and means to indulge in the ideals of the literati. The Nanga style grew out of the Southern School of Chinese painting where landscapes emphasized the sudden enlightenment of Zen Buddhism. This was just the opposite of the slow building-up process typified by the Northern (academic) School. One needed to grasp the essence rather than portray reality. The use of black ink with all its tonalities and the non-shaded solids where volume results from line made brush work of primary importance. Like Nanga it emphasized individuality and spontaneity. Along with their ideas and expertise, the Chinese artists also brought paintings and woodblock books. The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, compiled by Wang Gai, c.1679-1701, was published in Japan in 1748 and is still in print. Its step by step instructions for brush strokes gave Japanese painters a new vocabulary.

The Nanga painters had a long familiarity with the brush. Calligraphy was considered the highest form of art. The brush was a key element in the Scholars’ Three Treasures: painting, poetry, and calligraphy. Brushes work best on paper. The conical shape of the bristles allowed rapid, lively movement in any direction. The roundness of a solid could be expressed with a single stroke. Changes in the angle or direction of the brush, wrist, or arm, as well as changes in pressure or the amount of ink made possible a great variety of visual effects. In essence, the line was the man. Creation began with the grinding of the inkstick against the inkstone, went through the man and his brush and onto the paper. The one-point perspective of the West did not apply. Light, shadow, and background were not visual considerations. Look up, look down. Perspective was what one sees.

Kinkoku had little formal training. The figure paintings of the master poet-painter Yosa Buson greatly influenced him. (See SBMA Woman’s Board acquisition # 1967.18) His style, like the man himself, was more energetic and rougher than Buson’s. Whereas Buson used a more controlled line and his color washes stayed within the outline, Kinkoku used fewer strokes and was freer in his use of washes.

The Scholars’ Three Treasures of painting, poetry and calligraphy as used by the Japanese literati painters (Nanga) provided the basis for a truly Japanese art form called Haiga. The Haiga is part Haiku poem and part painting (ga). Haiku is a three line 17 syllable poem of 5, 7, 5 syllables respectively, and depends upon the observation and description of the everyday world expressed in common language. The poem is expanded by the picture. The poem, its calligraphy, and picture form a unit in which each element adds to the other, but not necessarily in a linear progression. The two combine to give an impression; the essence is the goal. The more powerful the poetic inspiration, the less the need for the pictorial, i.e. realism (John Rosenfield in Addis, 1995).

Around 1800, Kinkoku became a follower of Shugendo, a synthesis of esoteric Buddhism and the ancient worship of mountains as the sacred dwellings of native gods. Mountain climbing was both a physical and metaphorical means of working one’s way towards enlightenment. The activist approach to attaining enlightenment and the esoteric Buddhism concept that one could acquire supernatural powers in this life fitted well with Kinkoku’s impatient-restive temperament. The rugged wilderness was awe inspiring. His Buddhist training and adventure seeking personality added to the magical excitement of Shugendo changed both the subject matter and the style of his work. Landscapes of the sacred mountains were now his inspiration and his new patrons, Shugendo practitioners were eager for these landscapes. Peace and Prosperity under Heaven is neither a landscape nor a Haiga but it has the technical styles of both. The figures are travelers in a landscape. If one looks at the arrangement of overlapping figures and alternating tonality and line there is a sense of mountain. There is no poem, yet the figures are drawn with Haiga style where all superfluous description such as background elements are eliminated, and only a few brushstrokes are used to define the figures. It is an example of Kinkoku’s style of simplified forms, diagonal alignments and highly individual, energetic brushwork. Like Haiga which often includes visual or linguistic puns, Peace and Prosperity may even have this Haiga element. It is tempting to imagine the common sight and a New Year occurrence of the boy flying a kite as Kinkoku’s kite-flying escapade on the temple roof. Could the legendary 17th century ronin carving his latest poem into the cherry tree before battle also be seen as the artist painting a landscape or even this open air scene? Could not this have two levels of meaning, one a visual pun?

We have no artist’s notes, and meanings clear in 1809 may be lost in the present. It is only an amusing idea. Either way, Peace and Prosperity is absorbing and satisfying to view. What is clear is that the people and activities of Peace and Prosperity were a cross-cultural slice of country life, the myth associated with the New Year and the area where Kinkoku lived. All of this took place towards the end of the Edo period. The 188 figures depict mythical/legendary figures, the providers and consumers of goods and services and all strata of society.

There are at least 29 groupings of people and activities. (See annotated copy of scroll painting.) There are people playing games of chess, go and cards. Musicians entertain. Fortune tellers tell the future Women practice Ikebana. Venders sell noodles, rice cakes, sake, firewood and falcons. Men carve meat, make medicine, and dress the hair of a nursing woman. Mountain priests, a princess, a Shinto priestess, itinerant monks, a blacksmith and a groom wonder through. A monk practices calligraphy ( could this be Kinkoku the monk-Haiga painter?) and a boy flies a kite. Mythical figures such as Yoshitsane and Benkei with the temple bell warn off robbers; blind musicians protect against stumbling while falconers guarantee a good harvest. The legendary ronin (unaffiliated samurai) of the 17th century poem carves his latest poem into the cherry tree before going off to battle.

Peace and Prosperity under Heaven is a common phrase used by the Tokugawa government and a New Year greeting. Many of the activities depicted in this painting are common New Year sights. Peace and prosperity described the times and provided an economic climate and the leisure style supportive of these activities. In the center, there are two banners, each inscribed with the characters for Peace and Prosperity under Heaven and the 188 figures arranged around them. The sketchy, spontaneous and fluid brushstrokes and the patches of light color wash animate the scene. We have a "bird’s eye" view. The slight overlapping gives a shallow spatial depth. The hanging scroll format with its compact composition is meant to be read up and down.

Kinkoku’s life and work exemplify the ideals of the literati. He was considered one of the last major painters of the Nanga school. By painting Peace and Prosperity under Heaven in the technical styles of Nanga and Haiga, Kinkoku has shown us the people and customs of his countryside in a wholly Japanese style. Kinkoku eliminated the obvious and with self-assured, fluid strokes he presented the essentials. As we look at this scroll we learn, appreciate, get caught up in the crowd, and, finally experience a sense of calmness through line and tone, brush and ink. Line is the man.

Prepared by Jean McKibben Smith, Provisional Docent, SBMA, March 2001

Bibliography: Peace and Prosperity

Addis, Stephen, Haiga: Takebe Socho and the Haiku Painting Tradition, Marsh Art Gallery, University of Richmond in assoc. with University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1995.

Addis, Stephen, Japanese Nanga in the Western World, publishing data not given, curators file, SBMA.

Cheek, Patricia, Japanese "Sumi" Ink Painting, Docent files, SBMA.

Cheek, Patricia, Takebe Ryotai (1719-1774), Docent file, SBMA.

Fister, Patricia, The Import of Shugendo on the Painting of Yokoi Kinkoku, Ars Orientalis, vol. 18, 1988, pp. 163-195.

Fister, Patricia, Yokoi Kinkoku, , no publishing data given, curator’s file, SBMA.

Fister, Patricia, Yokoi Kinkoku and the Nanga Haiku World, Oriental Art, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 397-408

McArthur, Meher, Gods and Goblins , Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, CA, 91101.

Sagara, Tokuzo, Japanese Fine Arts, Japanese Tourist Bureau Library, 1949, #9.

Sweeney, Kyoko, Conversations, Docent, SBMA, 2001.

Tai, Susan, Collection Highlight, View Magazine, no date given, SBMA

Tai, Susan, Working Notes/Acquisition Committee, SBMA, 1999.