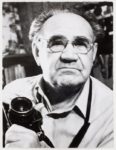

Yevgeny Khaldei

Russian, 1916-1997

Victory Reichstag, 1945 (printed later)

gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 11 7/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Joan Almond

2016.37.20

Yevgeny Khaldei (International Center of Photography)

"For Yevgeny Khaldei, every photo he took was very dear. It's not only the events he photographed but the people who participated in the events." - Anna Khaldei, his daughter

COMMENTS

The “Soviet flag over Reichstag” photograph is full of symbolism and represents a historic moment. Erected in 1894, the Reichstag’s architecture was magnificent for its time. The building contributed much to German history and was considered by the Red Army the symbol of their enemy. Soviets finally captured the Reichstag on 2 May 1945.

Next to Joe Rosenthal’s photo of raising the flag on Iwo Jima, Yevgeny Khaldei’s photo of Soviet soldiers raising a flag on top of the Reichstag building in Berlin is perhaps the most famous photo of World War II. But unlike the Iwo Jima photo, Khaldei’s Reichstag photo was both staged and doctored.

Khaldei’s photo was directly inspired by Rosenthal’s Iwo Jima photo. Noting the publicity the Iwo Jima photo had received, Soviet officials (perhaps Stalin himself) ordered Khaldei to fly from Moscow to Berlin in order to take a similar photo that would symbolize the Soviet victory over Germany. Khaldei carried with him a large flag, sewn from three tablecloths for this very purpose, by his uncle.

When Khaldei arrived in Berlin, he considered a number of settings for the photo, including the Brandenburg Gate and Tempelhof Airport, but he decided on the Reichstag, even though Soviet soldiers had already succeeded in raising a flag over this building a few days earlier. Khaldei recruited a small group of soldiers and, on May 2, 1945, proceeded to recreate the scene.

Back in Moscow, Soviet censors who examined the photo noticed that one of the soldiers had a wristwatch on each arm, indicating he had been looting. They did not want to impose that image on their country. They asked Khaldei to remove one of the watches. Khaldei not only did so, but also darkened the smoke in the background. The resulting picture was published soon after in the magazine Ogonjok. It became the version that achieved worldwide fame.

Later some Soviet sources claimed that the extra wrist watches were actually Adrianov compasses and that the Soviet Army touched out of the picture because they knew that this would be mistaken as a watch acquired by looting corpse rather than a piece of standard equipment. The Adrianov compass was a military compass designed by Russian Imperial Army topographist Vladimir Adrianov in 1907. Wrist-worn versions of the compass were then adopted and widely used by the Red and Soviet Army.

Subsequently, the photo continued to be altered. The flag was made to appear to be billowing more dramatically in the wind. The photo was also colorized. Throughout his life, Khaldei remained unrepentant about having manipulated his most famous photograph. Whenever asked about it, he responded: “It is a good photograph and historically significant. Next question please”.

German magazine Der Spiegel wrote: “Khaldei saw himself as a propagandist for a just cause, the war against Hitler and the German invaders of his homeland. In the years before his death in October 1997 he liked to say: ‘I forgive the Germans, but I cannot forget’. His father and three of his four sisters were murdered by the Germans”.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/soviet-flag-reichstag-berlin-1945/

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Yevgeny Khaldei’s 1945 photograph of the Soviet Union’s flag flying from the Berlin Reichstag is one of the emblematic images of World War II. In it, a Red Army soldier brandishes the Soviet flag from the upper reaches of the famous building as fellow soldiers assist. While it appears to capture a spontaneous act, in fact the photograph was staged. Khaldei placed a group of Soviet soldiers high up on the Reichstag’s exterior and directed one to unfurl the flag that Khaldei himself ordered up for the occasion. He further intensified the image by manipulating certain elements in the negative before printing, for instance adding the plumes of smoke rising in the distance. The image was published immediately the world over and provided stunning evidence of the utter defeat of the Third Reich, while also honoring (as the artist intended) the Soviet Union for its crucial and paramount role in the victory of the Allies.

Khaldei was a prolific World War II photographer whose vivid images captured many European combat flashpoints other than Berlin such as Budapest and Vienna. He went on to cover the Nuremberg trials and other internationally momentous events and milieus in the postwar era. Despite his achievements, Khaldei experienced degrees of anti-Semitism from Soviet authorities that caused him to struggle to maintain an entirely steady career in the following decades. Born in the year of the Russian Revolution, he died within a decade after the Soviet Union’s dissolution, and so witnessed the formation of today’s Russian Federation. Khaldei’s momentous life’s work has reached wide audiences in the past 25 years. A recent gift, Khaldei’s Reichstag image, his most famous, is on view here for the first time at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. It joins two previous gifts to present a concise and telling look into the dramatic career of one of the most important photographers of the Soviet era.

- Crosscurrents, 2018