Mike Kelley

American, 1954-2012

Apple Tree, 1982-83

acrylic on paper

41 1/2 x 50 in.

SBMA, Gift of Gerald Ayres

2010.53

Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

RESEARCH PAPER

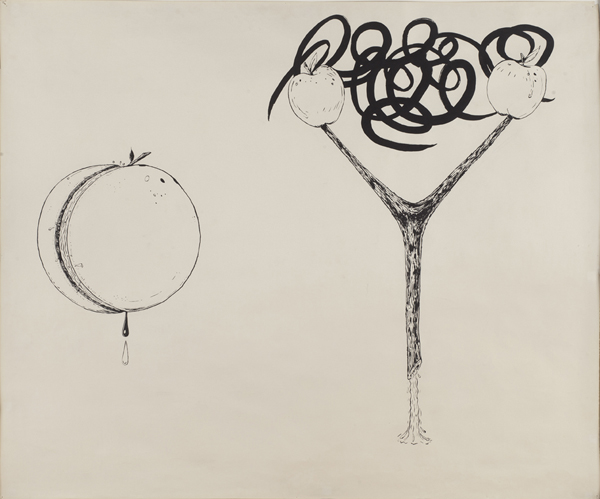

From a distance, this work presents as a charming line drawing, combining geometric shapes (circles and triangles) with a curvilinear geometric line. What appears from across the room as a stylized cocktail glass garnished with fruit or olives, coalesces, upon close examination, into a fanciful depiction of female anatomy (right) and a dripping circular shape that isn’t immediately identifiable. The “apple tree” of the title suggests female reproductive organs—ovaries (apples), fallopian tubes, uterus—crowned by a nest of pubic hair. The shape on the left is more curious: fruitlike in shape, is it a foreshortened, frontal view of a penis? A cervix? The two drops emerging from the bottom of the shape, one black, one white, don’t clarify what it is, but in keeping with the rest of the composition, it’s suggestive of fertilization. We are told, however, the unidentified shape is “a peach, which is an abstracted version of an inflamed monkey rump.” (SBMA Curatorial Label from “Left Coast: Recent Acquisitions of Contemporary Art, 2014.”)

“Apple Tree” is one of the 40 ink drawings that were part of artist Mike Kelley’s series of works called “Monkey Island,” which was exhibited at the Metro Pictures gallery in 1982, and at the Rosamund Felsen Gallery in 1983. Described as performance/installation piece, the exhibition included objects, drawings, and text in an installation-like presentation.

Kelley stated that the exhibition was inspired by a visit he made to the monkey enclosure at the L.A. zoo. He described Monkey Island as ‘an epic poem. . . a sailor’s tale. It’s a physiognomic landscape travelogue that seems to dwell mostly in at the sexual region.” (Metro Pictures Gallery Press Release.) Critics noted that “A prominent element of “Monkey Island” is a general critique of phallocentric modes of thought (notions concerning the phallus or penis as a form of male dominance), particularly those established by the renowned psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud.” (SBMA Curatorial Label, id.)

The Artist

Mike Kelley was born to a working-class family in a Detroit suburb in 1954, Kelley was the youngest of four children. His father was a maintenance supervisor in the public-school system and mother was a cook in the executive dining room of Ford Motor company. Both parents were devout Catholics, and Kelley had a tumultuous relationship with them growing up. He wanted to be a writer, but eventually turned to art and music, joining Detroit’s heavy metal music subculture in high school. He continued his involvement in that genre while attending college at the University of Michigan at Anne Arbor, joining a proto Punk rock band, “Destroy all Monsters,” which engaged in anti-establishment politics and Dada-like performance theatrics.

After graduating from the University of Michigan, he enrolled in graduate school at the California Institute of Arts in Valencia in 1978. Conceptual Art theory predominated the program at the time. While at CalArts, he continued to actively participate in the avant-garde music scene, joining another punk art band, “the Poetics,” whose work was described as performance pieces, soliloquies and poetic prose combined to make noise and deliver an anti-establishment message.

After graduating from Cal Arts, Kelley began creating multimedia installations that included large-scale drawing and paintings, his own writing, bits of sculpture, videos and performances. The themes were often scatological and/or sadomasochistic. He began to receive national attention in the early 80’s. He staged his work as one-man shows in New York and Los Angeles in 1982, and three years later exhibited at the Whitney Biennial. Again, these works were installation/performance pieces. Kelley created a performance work called “The Banana Man” in 1983, based on minor Captain Kangaroo figure, in which he appeared as Banana Man.

In 1987, Kelley began creating works using hand-knit blankets, rag dolls, sock monkeys and stuffed animals that he salvaged from thrift stores and yard sales. The best known of these works is “More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid,” in which he used stuffed animal toys and hand-knit afghans as a medium reminiscent, some said, of large-scale abstract impressionist paintings of the 1950s, and the push-pull paintings of Hans Hoffman. Some critics insisted that the stuffed animal works referenced child abuse and repressed memory, which Kelley always denied, but said that viewers should be free to interpret it as they wished.

Kelley continued to create challenging and difficult artwork for the remainder of his career, using multiple mediums including drawing, painting, sculpture, found objects, video and performance until his death by suicide in 2012 at the age of 57 in Pasadena, California.

Author’s Comment and Analysis

Kelley’s work is often complex and difficult, and defies traditional artistic notions of “beauty.” However visually appealing SBMA’s drawing, “Apple Tree” is at first glance, it is not representative of his larger body of work, or indeed the show in which it was first exhibited. Kelley did not present exhibitions composed of works in traditional media such as paintings, drawings, or sculpture. Instead, Kelley’s exhibitions were performance/installation pieces intended to challenge traditional notions about the nature and purpose of art. Key to understanding his body of work is understanding and recognizing his roots in the nascent punk rock movement and his formal training and background in the Conceptual Art movement, both of which were devoted to challenging authority and challenging viewers to question traditional values.

Where is his place in the contemporary art pantheon? Why did he achieve such acclaim? Kelley’s work, while “physically messy and psychologically complex,” is credited with laying the groundwork for present-day installation art.” (Jori Finkel, Los Angeles Times, Feb. 2nd 2012) “L.A. would not have become a great international capital of contemporary art without Mike Kelley. . . Of all the artists in the 1980s, he was the one who really broke out and established a new and complex identity for his generation.” (Id., quoting Paul Schimmel, chief curator of Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.)

Moreover, Kelley is credited by some with “picking up where Pop Art left off.” Said one critic: “When he was growing up in a Detroit suburb, the art establishment reveled in Andy Warhol’s slick appropriation of soup cans and Hollywood starlets. But by the time Kelley reached adolescence in the 1970’s Detroit’s car factories were shuttering and whatever pop culture he encountered didn’t gleam—it sneered: Iggy Pop and the Stooges; Sex to Sexty, a cheeky comic; school hazing rituals; and soiled stuffed animals. Could fine art really be made from middle-class vernacular? Did the basements of America have anything profound to say? Kelley was among the first to seek an answer.” (Wall Street Journal, Kelly Crow, “The Escape Artist,” March 14, 2013.)

SBMA guests can contemplate these questions and form their own opinions, even as they appreciate the whimsy and enchanting lines of his “Apple Tree.”

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Mary Ellen Alden, 2020

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Interview Magazine, Glenn O’Brien, “Mike Kelley,” Published November 24, 2008 located at:

https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/mike-kelley

PBS, “Art:21—Art in the Twenty-First Century,” Season 1 2001, located at:

https://www.pbs.rg/art21/artists/kelley/

Los Angeles Times, Christopher Knight, “Art Review: Nothing Like a Little Enlightened Impurity: A mid-career survey of Mike Kelley’s work underscores the artist’s scathingly funny and insightful touch,” July 1, 1994, located at:

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-07-01-ca-10566-story.html

The New York Times, “Mike Kelley, an Artist with Attitude, Dies at 57,” Holland Cotter, February 1, 2012, located at:

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/02/arts/design/mike-kelley-influential-american-artist-dies-at-57.html

SBMA, Press Release, “Exhibition Features Recent Acquisitions by Works by Southern California Artists Left Coast: Recent Acquisitions of Contemporary Art. 2014,” located at:

https://www.sbma.net/exhibitions/leftcoast14

Los Angeles Times, Mike Kelley dies at 57; L.A. contemporary artist, “ Jori Finkel, February 2, 2012, located at:

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-xpm-2012-feb-02-la-me-mike-kelley-20120202-story.html

The Art Story, “Mike Kelley American Sculptor, Conceptual, Performance, and Video Artist,” located at:

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/kelley-mike/

Wall Street Journal, Kelly Crow, “The Escape Artist,” March 14, 2013, located at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324678604578340322829104276

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Apple Tree is one of forty ink drawings that are part of Mike Kelley’s notorious multimedia series of works called “Monkey Island,” which includes works on paper, sculptures, installations, and a major performance. Prevalent in Apple Tree, along with much of the artist’s oeuvre, is the embrace of failure, found in references that range from banal to obscene and horrific. The imagery in this drawing represents anatomical parts—on the left, a peach, which is an abstracted version of an inflamed monkey rump; and on the right, a uterine-shaped wishbone with apples (which may also be seen as ovaries). A prominent element of “Monkey Island” is a general critique of phallocentric modes of thought (notions concerning the phallus or penis as a form of male dominance), particularly those established by the renowned psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud.

- Left Coast: Recent Acquisitions of Contemporary Art, 2014