Paul Jacoulet

French , 1902-1960

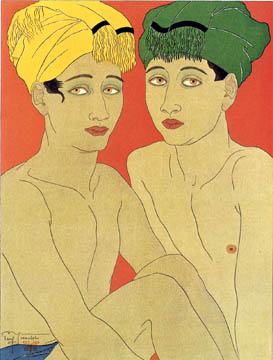

Yellow Eyed Boys, Ohlol East Carolines, 1940

woodblock print

15 1/2 x 11 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Roland A. Way

1991.147.32

Undated photograph of Paul Jacoulet

In the words of Richard Miles, author of “The Prints of Paul Jacoulet”: “As much as William Blake or Edvard Munch, Paul Jacoulet was an eccentric,solitary genius whose art, like theirs, comes from a unique imagination.”

RESEARCH PAPER

The title of this print in French is “Les Enfants aux Yeux Jaunes – Ohlol Est Carolines” which translates as “The Children with Yellow Eyes – Ohlol East Carolines”, Ohlol being a village or town in the East Caroline islands of the South Pacific. Jacoulet’s favorite subjects were the people and culture of the South Pacific islands that he visited as a young man, so this print, although an atypical subject for him, was one of Jacoulet's most successful images, as evidenced by the fact that the Federation of Micronesia chose to publish a set of stamps featuring three of his prints in 1991, more than 30 years after his death, one of which was “Yellow Eyed Boys”.

The first thing we notice about this print is the provocative use of large areas of vivid colors, unlike the more typically smaller or graduated areas found in traditional Japanese woodblock prints. These solid color areas are absolutely delineated by the exquisite use of line which outline and define the 2 boys and demonstrate the drawing skill Jacoulet learned through his training in Japanese brush-painting. The color palette is also much narrower than we observe in traditional woodblock prints. The are perhaps only 10 or fewer colors used in this print. This implies that the number of blocks used for this print was much less than Jacoulet’s typical prints which could require 50 to over 200 blocks. But here, the limited palette adds to the starkness of the image.

As to the subject matter, I think we can safely say that the typical museum viewer would find it quite strange. The two almost naked “boys” sit very close to each other and stare out at us with questioning and unsure eyes. Their eyes and eyebrows look to be accentuated with eye makeup and their lips are strikingly red as if hidden under lipstick. The left-hand boy has a lock of hair that seems to be purposely arranged so that it is exposed very so slightly from beneath his headdress and carefully arranged and delicately curled. The overall effeminate nature of the boys could perhaps imply a homosexual relationship. On both boys, the black hair seems to direct our attention to their eyes, which of course is the main focus of the piece.

I could not find any information that would suggest that Jacoulet was gay, but he did have a few strange behaviors, such as appearing in public with his face covered with white powder much like a Geisha would do and ultimately being buried with his face painted like a geisha. Around 1955, the US had denied him his entry visa because the Department of Immigration “had been alerted to his eccentricities”. One can only speculate what eccentricity would be sufficient enough to preclude a well known artist from entering the US.

His Art

Fresh ideas, not imitations of the traditional Japanese woodblock style, set Paul Jacoulet’s work apart from what the world was accustomed to. His combination of Western culture, love of Japanese culture, and skill in Japanese woodblock technique created a unique artistic style.

Few art critics championed him. He had contempt for the art professionals of his day, which was reciprocated.

By the 1930s, woodblock ukiyo-e prints in Japan were now out of favor. Paul thought that he might be able to revitalize them with different non-traditional subject matter, i.e., his images from the life and culture of the South Seas.

With the help of the French Embassy in Tokyo, Paul got the opportunity to have Kazao Yamagishi, a famous artist and carver, evaluate Paul’s designs. Yamagishi’s reaction was very encouraging:

“Even the slightest details show refinement and taste. Above all, Jacoulet is careful where other artists are negligent... As to color, his effects are thoroughly Japanese. In many respects, there is no Western artist working in this medium who can approach him, and even among Japanese artists, he stands out. “

For the next two years, Yamagishi carved and printed fourteen of Paul’s works.

The late 1930s was the greatest creative period of his life, which included the creation of his first woodblock print. Rather than selling his work through dealers, he pursued the idea for selling his prints through subscription, in addition to his exhibitions. He never had a major art dealer and he didn’t want his works to be like the mass produced Japanese woodblock distribution of the Edo period.

In Japan at the time, one school thought artists should do their own carving and printing, but Paul disagreed. He thought each process should be done by an expert in that particular field and that artists should do what they do best: paint and draw. Paul became his own publisher and oversaw the printing of his works. He emphasized the importance of his carvers and printers by including their names or stamps on his prints. Although his prints found favor with many visiting westerners, his subjects were sometimes an affront to conventional Japanese tastes of the time.

In the 1950’s, he sought popular acceptance and wrote to collectors “I am the greatest artist...” Perhaps as a way of promoting himself, he made sure his works were in the collections of prominent people like Douglas McArthur, Harry S. Truman, Greta Garbo, Edward G. Robinson and Pope Pius II by gifting prints to them. In the post WW II period, he did finally gain worldwide attention from an article in Time magazine although some critics called his work shallow. Many works depicted a dying world rather than a world of transitory pleasure as in Ukiyo-e ‘floating world’ images. His botanically accurate flowers and fruits were imperfect with their bruises and insect infestations. The Shoji screens in his backgrounds were mended or tattered.

He abandoned standard conventional poses. His subjects’ hands and facial expressions revealed resignation, lust, and joy. Unlike traditional Japanese woodblock prints, there were no classical faces or gestures or time-faded colors. But he did introduce new innovations that went beyond classical Japanese woodblock printing techniques. Few artists used as many precious metals and natural pigments in devising new shadings.

During his lifetime, Paul Jacoulet produced 30,000 woodblock prints and several hundred fine watercolors, many of which have been lost.

In summary, the inclusion of Yellow-Eyed Boys in a docent tour affords an opportunity to compare the technique and style of this work to our Japanese woodblock prints that are on permanent display.

His Life

Paul Jacoulet was born a sickly child in Paris on January 23, 1902. Shortly thereafter, his father left Paul and his mother in Paris and went off to Tokyo to work as a language tutor. Four years later in 1906, Paul and his mother joined his father in Japan.

There, Paul received a formal education by attending elementary and middle schools and received an education no different from that of a Japanese boy. He acquired a deep understanding of the language and literature of Japan plus an understanding of its traditions and customs. He was also tutored in painting, drawing, calligraphy, Japanese brush painting, and music, all of which he loved. He became an accomplished linguist, calligrapher, watercolorist, and musician, playing both the violin and Japanese ‘samisen’. (A Japanese musical instrument resembling a lute, having a very long neck and three strings played with a pick.) Throughout his youth, he loved studying and drawing insects and butterflies and finally collected hundreds of thousands of them during his lifetime.

With the advent of World War I, Paul’s father returned to France by himself to serve in military while Paul and his mother stayed in Tokyo. During the war, the use of poison gas caused 200,000 casualties in the French Army and unfortunately Paul’s father was one of them.

Paul found work at the French Consulate as an interpreter, which he hated, and during this period his art was neglected. At 18, Paul, now charming, talented, fluent in Japanese, and dressed in the latest Paris clothes, was in social demand. Years later, a French diplomat’s wife who knew him described him as “certainly the best-looking young man in Tokyo.”

In 1923, a great earthquake leveled and burned Tokyo but Paul’s house was spared although close by houses were not. Perhaps Paul saw this as an omen, since shortly afterward he picked up with his art again. But his friends noticed an almost total abandonment of his previous ukiyo-e style in favor of experimenting with ideas he discovered on his trips to Paris. During these trips, Paul would spend hours enthralled with the South Seas images of Paul Gauguin. His mother encouraged him to travel and see this remote part of the world in hope that the warmer climate would be better for his health.

During his exploration of the many islands in the South Seas, he was accepted by the natives into their lives. Instead of focusing on drawing the beautiful native women, he preferred to document the stooped and the sickly. He also portrayed the disappearing bird and plant life that he felt foreshadowed the inevitable disappearance of their human counterparts, caused by the militarization of the South Seas by the Japanese and, in general, by the encroachment of modern civilization. In some cases, Jacoulet was the only chronicler of the native people whose villages and islands that effectively ceased to exist later in the century. His drawings and paintings done during these travels would later become the basis for his woodblock prints.

Around 1924, his mother remarried and moved to Seoul Korea where she died in 1940. During his visits to see her, he again used his talent for drawing to capture images of Korean people that he would later also use in his art.

As World War II approached, life in Japan became more difficult. In 1941, After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, art materials became scarce. As a foreigner, he was constantly under observation by Japanese authorities so Paul moved out of Tokyo.

In the early1950’s, he wanted to go around the world to visit friends and customers and do more drawing in Australia, New Guinea, and the South Sea islands. He also wanted to do a new project of 120 prints of the disappearing peoples of the Asian and Pacific world, hoping these would bring him fame in his native France. He did do the world tour but U.S. Department of Immigration “had been alerted to his eccentricities” and he was refused a visa to enter the US.

By the mid 1950s, his health was seriously deteriorating. Despite pain and recurring depression that could bring him to tears at the slightest provocation, he worked hard on his print project. But in 1960, he died of diabetic shock. He was buried in Japan next to father, his face painted like a geisha.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Peter D. Neuhaus, 2/1/06

Bibliography

Richard Miles, The Prints of Paul Jacoulet, A Complete Illustrated Catalog,

Robert Sawers Publishing, London (in association with Pacific Asian Museum), 1982

Florence Wells, “Paul Jacoulet: Wood-Block Artist”, Contemporary Japan, Vol 24, Nos 7-9 & 10, 1956-57

Andrew Horvat, ”Karhu and Jacoulet - Western Artists Working in an Eastern Medium”, The Japan Quarterly, October-December 1994. See http://www.cic.sfu.ca/horvat/Jacoulet.html

Far Outliers, (A website exploring migrants, exiles, expatriates, and out-of-the-way peoples, places, and times, mostly in the Asia-Pacific region), “Karhu and Jacoulet - Foreign Japanese Woodblock Print Artists”,

http://faroutliers.blogspot.com/2004/01/karhu-and-jacoulet-foreign-japanese.html

International Fine Print Dealers Association, “Paul Jacoulet – Artist Profile”,

www.printdealers.com/artist_template.cfm?id=743

Artelino Art Auctions, “Paul Jacoulet”, www.artelino.com/articles/paul_jacoulet.asp

Castle Fine Arts Gallery, “Paul Jacoulet”, www.castlefinearts.com/fs_biography.aspx?page=/Japanese_fine_arts_woodblock_prints/Paul_Jacoulet_Biography.aspx

Hanga Gallery, ”Paul Jacoulet Surimono Prints” (sixteen miniature prints),

http://www.hanga.com/western/jacoulet/surimono.cfm

The Ren Brown Collection Gallery, “Paul Jacoulet” (List of exhibitions),

www.renbrown.com/cgi-bin/ustorekeeper.pl?command=goto&file=JACOULET_Paul.html

Floating World Gallery Ltd., “Paul Jacoulet”, (bio and photo),

www.floatingworld.com/docs/ref_ArtistDetail.asp?art_ID=89

Artelino Art Auctions, Clifton Karhu, www.artelino.com/articles/clifton_karhu.asp

Viewing Japanese Prints, “Paul Jacoulet”,

http://optometry.berkeley.edu/~fiorillo/texts/shinhangatexts/shinhanga_pages/jacoulet3.html

Justwendy Thematics Stamp Dealer, (Micronesia Jacoulet stamp sets), www.justwendystamps.com/shop/ItemDetails.asp?ProductRef=7166&ThemeID=104&KeyWord=&StartPage=11&Theme=ARTS