George Inness

American, 1825-1894

Morning, Catskill Valley, 1894

oil on canvas

35 3/8 x 53 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Sterling Morton to the Preston Morton Collection

1960.66

Inness seated in his studio with a brush in his hand and his hat in his lap. Inscriptions lower right: "Yours Respectfully, Geo. Inness." Annotation on verso (handwritten): If you have Fifty-Eight Paintings by George Inness*, you may be able to identify painting in easel. *by Eliott Dangerfield, published by F.F. Sherman.

“The purpose of the painter is simply to reproduce in other minds the impression which a scene has made upon him. A work of art does not appeal to the intellect. It does not appeal to the moral sense. Its aim is to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion.” - George Inness

RESEARCH PAPER

"Morning, Catskill Valley" is a landscape serene and sensuous. It was painted in the last year of Innes' life and ignores the great industrial surge, which was transforming America in his presence. Even in 1855 when he documented the achievements of the new age and its great artifact the railroad in "The Lackawanna Valley" (Powell, National Gallery Washington, 234), Innes managed to aestheticize the train so that it drove cheerfully at middle distance through the verdant hills and dales, a far cry from the ominous oncoming machine on JMW Turner's bridge in "Rain, Steam, and Speed" (Levey, National Gallery, London, 207).

Inness conveys the Edenic innocence of the Catskill Valley by an almost impressionistic style and shows countryside small in scale and intimate in feeling. There is freshness, informality, an emphasis on the effects of light and atmosphere. Animals and man are unobtrusive, of little interest themselves. They only certify the bucolic scene. The painting has rich ravishing colors in the autumn hues of trees and the soft muted brushwork. There is a hush, stillness, and a tranquility of mood. Even the clouds seem only to hover rather than surge across the fall sky. The stream barely ripples.

But though nature may be tame, the artist was not. Innes proudly and mystically determined to give a personal vision to his work: nature arranged and colored as he wished it to be seen. Referring to a similar picture, "Autumn Oaks" (in the Metropolitan Museum of Art), Innes wrote, "Was it done from nature? No, it could not be. It is done from art, which molds nature to its will and shows her hidden glory" (quoted in Werner, Innes Landscapes, 84).

Innes was largely a self-taught artist, temperamental and spiritually troubled. He changed churches several times and finally joined the Swedenborgian Church of the New Jerusalem, a mystical cult that attracted many intellectuals and artists. He was epileptic from childhood and often in precarious health though he married, had a large family, and traveled to Europe four times for extended periods where he saw the seventeenth century pastoral masters Claude and Poussin and was much influenced by the contemporary French Barbizon School. He strove to evoke a poetic state of mind by relying increasingly on light and color to reveal a hidden deeper reality available to men's souls if powerfully guided. Many of his contemporaries such as Thomas Cole (see his "The Meeting of the Water") or Joseph Cropsey (see his "Janetta Falls") presented the spectacle of the wilderness as primitive, storm-ravaged, sublime, awe-inspiring. Innes was much more given to mature domesticated 'civilized landscapes,' of which the "Catskill Valley" is a superb example.

For Innes the process of painting was a reverential art; it cultivated spirituality and was spiritually regenerative. Innes was a true if idiosyncratic believer in the Swedenborgian Church and produced a theory of color of enormous complexity derived from its philosophies. Colors, he maintained, exhibited spiritual properties determined by an intrinsic relationship between particular hues and particular spiritual qualities. The true artist was to create images beyond the "outer fact" and "surfaces" and thus reveal the "moving spirit" of an "inner life." In this case, divine things and heavenly secrets are revealed with red corresponding to God's love and the commitment to practice love of neighbor. But even for those who do not share this faith, the reds of the tress and their muted reflection in the waters below inspire the feeling that some god is in this place. (For a discussion of these theories at great length, see Sally Promoy, The American Art journal, 51-60.)

Innes died while walking in the Scottish countryside, communing with the landscape and nature that he had celebrated, shaped, and spiritualized in life.

Provenance: Inness Executor’s Sale, 1895; purchased by Charles E. Clarke, still in collection by 1908; William S. Skinner, New York; Robert Steward Kilborn; purchased from Kilborn by Knoedler and Company, New York, August 27, 1959; purchased from Knodler by Mrs. Sterling Morton for PMC 1960. (Preston Morton Catalogue, 114)

Condition and technique: A 1978 examination by the BACC noted that the painting had been lined with wax resin to a fiberglass fabric. The tacking margins were extant with wide-mouthed traction crackle in the sky along the top, and in the central red tree was apparent. The painting had suffered slight losses along the edges, probably from the lining. The design area may have been slightly extended in lining. The moderate matt surface coating was estimated to be a thin recent coating of synthetic polymer resin. The overall condition of the painting was good. (Preston Morton Catalogue, 114.)

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Paul McClung, March 27, 1997

Website Preparer: Cliff Hauenstein, January, 2004

Bibliography

Cikovsky, Nicolai, George Inhes. New York, 1993.

Ireland, Leroy, The Works of George Innes. Austin, 1965.

Levey, Michael, The National Gallery Collection, London, 1991.

McCausland, Elizabeth, George Innes. New York, 1946.

Mead, Katherine Harper, The Preston Morton Collection of American Art, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1981.

Powell, Earl A., The National Gallery of Art, Washington. London, 1995.

Promoy, Sally, "George Innes, Color Theory and the Swedenborgian Church," The American Art Journal, vol. xxvi, 1994: 45-59.

Schama, Simon, Landscape and Memory, New York, 1995

Werner, Alfred, Innes Landscapes, New York, 1973

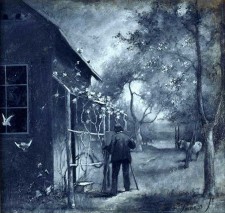

“George Inness Sketching Outside his Montclair Studio”, circa 1889, by George Inness, Jr., oil on canvas board, collection of the Montclair Art Museum.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This is an example of the late style of Inness, after his absorption of the lessons of the Barbizon school of painting in France, with its emphasis on painting outdoors, directly from nature. The rich colors and loose brushwork are typical of this phase of Inness’s artistic development and are quite distinct from the more classically inspired idiom of his early years. Though generally naturalistic, the serenity of this lushly described fall landscape may also reflect the spiritual teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), according to whom nature is imbued with an almost otherworldly radiance that reflects a higher realm.

- Ridley-Tree Reopening, 2021