Edward Hopper Study with James Glisson, Curator of Contemporary Art

June 3rd, 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic, click here.

(video 5:40)

Edward Hopper

American, 1882-1967

November, Washington Square, 1932, 1959 (sky added)

oil on canvas

34 1/8 × 50 1/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Sterling Morton

1960.64

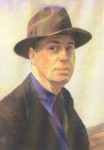

Edward Hopper, Self Portrait, 1925-30, Oil on canvas, 25x20 in.,Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC.

“Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist,” – Edward Hopper

RESEARCH PAPER

Edward Hopper was born in Nyack, N.Y. in 1882. He died in 1967 in the same New York flat and studio overlooking Washington Square that he had lived in for most of his life. His precocious drawing talent was supported by his parents and Hopper was working with charcoal, pen and ink, watercolor and oil by his early teens. Nature and political cartoons preoccupied him while he also copied other artists as a way to learn his craft. He studied painting with Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller at The New York School of Design (now Parsons) from 1900 to 1906, commuting from Nyack. He came from a comfortable, conservative middle-class Baptist family. He enjoyed the same 19th century French and Russian literature and art as his father while also being influenced by a wide range of 19th century artists and writers including Edgar Degas, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emile Zola and more. Goya and Rembrandt were influences from earlier centuries.

Recognition came slowly, and Hopper struggled to keep painting in the years after his training ended. He had learned how to do illustrations while in art school and now had to return to making advertisements, something he disliked. However, he began to be noticed in the 1920’s with large scale exhibitions at the Whitney and the Modern Art Museum. Awards followed and his career proceeded in a regular way with his art commanding ever higher prices. He and his painter wife Josephine Nivison lived a quiet life overlooking Washington Square Park with regular summer travels to Cape Cod.

Hopper is routinely called “the quintessential American Realist” (Levin,1998, p.5), or as influenced by Impressionism (Renner, R. 1971/1983, p. 15). Neither category is sufficient to describe a complex artist trying to navigate an ever-changing art scene at the time. Like all aspiring American artists, Hopper made his way to Paris several times but significantly showed little interest in the exciting new Cubist developments pioneered by Picasso and Braque. Back home, he had more sympathy with the rebellion against the seemingly romantic and idealizing art of American landscape painters—a rebellion promoted by his teacher Robert Henri, founder of the Ashcan Art group. Henri was developing a new style of Realism and wanted painters to reveal the true life of people in all its ugliness and surprising beauty, and to make documentary-like interventions.

Hopper was not that kind of Realist: He was a realist in the sense of painting objects in the real world, but he did not paint humans going about their daily activities. His realism rather involves exploring the relationship between humans and their environment, whether that was the city or the country. Many of his paintings show people (often featuring his wife) in rooms with doors or windows to the outside, sitting silently, still. Their bodies seem tense, and they appear to be waiting for something to happen. They often seem to be reflecting or thinking, but at any rate frozen in place, waiting to be prompted to move.

Hopper’s city buildings, my focus here, also seem to be steeped in silence. Yet, perhaps paradoxically, they are less melancholy than paintings with people in them. Hopper loved buildings, a love perhaps related to his interest in becoming an architect earlier in this life, inspired by the unique Nyack Victorian houses. He once said that slapping a coat of paint on a building in one of his works was a deep pleasure (Goodrich, p.11). The first years of being in the Washington Square studio were years when he was discovering the new living spaces around him and getting attached to them. The series of city paintings [including “Roofs” and “Skyline Over Washington Square,” (both 1925), “The City” (1927), “My Roof” (1928) and “City Roofs” (1932) all share a warm range of colors including dark brown, autumnal red, pale yellow, rusty brown. They also share a feeling of situatedness, of something solid, grounded. They rarely include humans or animals, or even the distraction of a tree, greenery, or other objects such as flowers, cars, sidewalks etc. The images are filled with buildings mainly without windows, doors, or decoration. But the effect is warm instead of the more familiar bleak feeling of many of Hopper’s works.

Hopper’s painting, “November, Washington Square,” my focus here, was the last in the series noted above. It depicts the view of the Square from Hopper’s home at 3 Washington Square North, after he exchanged studios with his wife, Jo Nivison. He now had a view across the Park. But after starting the painting in 1932, Hopper abandoned it until 1959 when it was finished, and a stretch of blue sky and puffy clouds was added, bolstering the warm feeling. No reasons for the interruption have been given, but the 1929 Depression was well underway and may have further influenced Hopper’s often melancholy mood and his tendency to depression—both of which interfered with his painting.

“November, Washington Square” shares the characteristics of the previous paintings of buildings but adds important elements that extend the meaning beyond the earlier works. The colors of the buildings are a pleasing brown and faded red, as in the earlier works, but the view is brightened by the alluring gold of the Judson Memorial church which catches the eye immediately. It is interesting that the church with its gold is not quite at the center of the painting. It rather creates its own circle taking in the buildings to the left which do have windows and then moving to branches of the dead tree in the foreground which leads our eye out to the church, and then on to a tower dimly seen in the distance. The right of the painting includes the circular concrete shape of the edge of a fountain, where two tiny birds can be seen, We are pulled back by this concrete and thus have what the other paintings lacked, namely a perspective on the church. The tower of the church stands out as a result.

Because there are more details in this painting than in the others (there’s the tree even though it looks dead and the two birds sipping water from the fountain) the absence of humans has more impact. The lack of reference to humans in the earlier paintings goes unnoticed because the objects themselves are so present, solid, there. But in the later painting, the absence presses in on the viewer at first. It’s as if Hopper himself is giving life and warmth to the park, trying to warm it up, so to speak. He fills in the absences through his very human love for the buildings, and through his careful use of lighting. The gold represents this warm feeling vividly.

These paintings redefine a loneliness often applied too easily to Hopper’s work, leading him at one point to say that the attribution of loneliness was overdone, even if it had a germ of truth. According to Gail Levin, “Hopper transformed reality, creating a space that corresponded to his distressed mental state of the moment….” (Levin, xi). But this is only partly true and does not take account of Hopper’s sense of the sheer beauty of buildings that make him feel alive.

Hopper was influenced by Freud and Jung. He indeed believed that painting reached deeply into the artist’s unconscious and allowed unknown feelings to be expressed. This deeper level of the art work was expressed through light and shadow, or through the menacing impact of a window opening out onto total darkness outside as in so many of his paintings. Often only showing one human being in the frame, Hopper’s art increases the sense of the ultimate, existential loneliness we all face. Hopper paints real worldly spaces of civilization and he loves some of these spaces as we’ve seen: But Hopper’s realism is not one that stays on the level of the object itself. He always penetrates to the underlying emotion hidden from sight—an emotion at once personal and at a deeper level linked to the very fact of being human.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Elizabeth Ann Kaplan, February 2025.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goodrich, L. (1971/83). “Edward Hopper: New York.” Taschen.

Kranzfelder, I, and Edward Hopper. (2003). “Edward Hopper, 1882-1967: Vision of Reality.” Barnes and Noble.

Levin, G. (1998). “Hopper’s Places.” University of California Press.

Levin, G. (1995). “Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography.” Alfred A. Knopf.

Renner, Rolf G. (2021). “Hopper: Transformation of the Real.” Taschen Press.

Strand, Mark. “Hopper.” (1994). Knopf.

Wagstaff, Sheena, ed. (2004). “Edward Hopper.” Tate Publishing.

COMMENTS

Edward Hopper is known primarily as a realist painter of his surroundings. He first rented his New York studio at 3 Washington Square North in late December 1913, and, although he later took over additional space on the floor, he remained there until his death in 1967. Thus, his painting, November, Washington Square, begun in 1932, represents a view he knew intimately –the view directly across from his studio on the south side of Washington Square Park. In 1899, after graduating from high school in his hometown of Nyack, New York, Hopper commuted daily to New York City to study illustration, which his parents insisted offered a more secure income than painting. The next year he enrolled at the New York School of Art, where he eventually studied painting with William Merritt Chase, Kenneth Hayes Miller and Robert Henri.

Hopper traveled to Europe in October 1906 in order to study the great masters. Upon his return the following August, he worked for an advertising agency three days a week to support himself while painting. After two additional trips abroad in 1909 and 1910, he took a studio in New York, but continued to live with his parents and sister in Nyack commuting daily for the next several years.

When Hopper’s new neighbor Walter Tittle returned from a Christmas visit home to Ohio in January 1914, he learned that the adjoining studio was occupied by his former classmate, who, like himself, was now a struggling artist and illustrator. Tittle, recalling that Hopper was then preoccupied with French subject matter and style, noted of Hopper: "for a considerable period his principle product consisted of occasional caricatures in a style smacking of both Degas and Forain, and drawn from memories of his beloved Paris."

By February 1915, when he exhibited in a group show at the MacDowell Club of New York, the negative critical reception that his monumental painting Soir Bleu of about 1914 had received as a French "fantasy" contrasted with the praise his New York Corner (well known today as Corner Saloon) received as a perfect visualization of New York atmosphere." The growing tide of cultural nationalism encouraged Hopper to turn to his immediate surroundings for his subject matter. By the late 1920’s, he was repeatedly praised for the "Americanness" of his paintings.

Hopper noted in his ledger that November, Washington Square was "Painted in New York studio about 1932 or 1934" and that the "sky (was) added in June 1959"; he also indicated "Colors and canvas unknown, probably zinc white." The delay in finishing painting the sky, caused by Hopper’s anxiety about ruining a picture, happened more often with his watercolors. Sometime, as in his watercolor, Cabin, Charleston, South Carolina (1929), included in the Hopper bequest to the Whitney Museum of American Art, he failed to find either the courage or the time to complete the sky. Until the end of his life, even after much success, Hopper remained vulnerable to critical evaluations of his work. Comments less than enthusiastic probably provoked lingering feelings of self-doubt left over from years of struggling for recognition. Late in life Hopper remarked of artists: "Ninety per cent of them are forgotten after they’re dead."

Although there is not a group of preparatory sketches for November, Washington Square, there is one closely related drawing entitled Washington Square and Judson Towers, which Hopper liked well enough to give to his friend Mrs. John O. Blanchard. On the back of a reproduction of this drawing from the Nebraska Art Association Annual Exhibition catalogue of 1959, Jo Hopper noted "This drawing done from Was.Sq.N. roof." Thus, the similar view in the painting could also be seen from the roof of the Hoppers’ home. In 1932, the year Hopper remembered beginning this canvas, he and Jo took over additional space on their floor in 3 Washington Square North.

The view from his roof, and from two windows, in his apartment, is down across Washington Square Park to the Judson Memorial Church, built during the last decade of the nineteenth century. Hopper depicted the church’s square bell tower topped with a cross dramatically silhouetted against the sky. In the foreground of his painting, a tree, left bare by winter, provides a striking counterpoint on the lower left of the composition. Hopper made the composition of this painting more effective than that of his related drawing by eliminating the distracting edge of the roof and its protuberances and focusing directly on the view itself. He often painted views from his roof in the city, and occasionally made watercolors from rooftops while traveling, such as those in Saltillo, Mexico,

painted in 1946.

Hopper especially liked painting architectural forms and capturing the drama of light and shadow. He stated that he had disliked having to illustrate because he had to draw people "grimacing and posturing" when "What I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house."

The Hoppers were proud to be living under the same roof where so many celebrated figures had passed, including Ernest Lawson and William Glackens of The Eight e.e. Cummings, John Dos Passos Rockwell Kent, and Thomas Eakins. All of these feelings must have gone into Hopper’s thought when he chose to paint this view from his house. He chose November, the month he and Jo usually returned from a long summer spent on Cape Cod. His decision to present this busy city square deserted indicated his preference for the quiet calm of early morning when introspective thought could best be entertained.

Gail Levin

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Edward Hopper was born July 22, 1882, in Nyack, New York, to Elizabeth Griffiths Smith and Garrett Henry Hopper. After studying illustration in New York, Hopper, between 1906 and 1910, traveled on three different occasions to Europe, where it was Impressionism and not the more recent avant-garde movements that had the greater effect on his art. He was enthralled by the quality of light he found in Impressionist works. As he later commented: I’ve always been interested in light – more than most contemporary painters."

Until 1924 Hopper earned his living as a commercial illustrator for books and by publishing in periodicals such as Sunday Magazine, Adventure, and Scribners’. His 1918 poster, Smash the Hun, completed as a competition piece for the United States Shipping Board, won Hopper a first prize and his first national acclaim as an artist. He also did posters for the movies and the American Red Cross.

Hopper exhibited in the Armory Show of 1913 and sold his first painting, an oil, for $250. It was soon after this that Hopper moved into his Washington Square North studio. In 1915 a friend and fellow illustrator, Martin Lewis, taught Hopper how to etch, and until 1928 Hopper did very little painting. Instead, he produced over sixty prints that Goodrich describes as his "fully mature style" where "within the limits of black and white, he finally found himself." Works from this period like Evening Wind (1921) or American Landscape (1920) exemplify Hopper’s intense vision and confrontation of subject. Zigrosser compared Hopper to Robert Frost or Thomas Eakins in his "clear sighted vision . . . integrity of character and tenacity of purpose." In 1924 Hopper married the painter Josephine Verstile. They led a quiet, solitary life devoted to work, dividing their time between New England summers and New York winters, with one trip to Mexico in the 1940’s.

Hopper depicted the American scene in a direct yet unique way. Throughout his career he repeatedly turned to representation of single figures, barren settings, and bleak architectural prospects. His concern for the poignancy of American life – especially the loneliness experienced in the American city – remained the constant. The painting of the 1950’s and 1960’s look much like the paintings done in the 1920’s, but instead of becoming banal through repetition Hopper’s view becomes one of clarity. By paring down to essentials Hopper imbues his scenes with a quality that is at once emotional and physical. As William Seitz has written: "No portrayal in art of a nation as vast and diverse as the United States can be anything but fragmentary . . . Hopper’s images ring so true because they reflect personal conviction and feeling rather than a program of social comment. The truth to which one responds is that of art distilled from life."

- Kathleen Monaghan, The Preston Morton Collection of American Art, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Katherine Harper Mead, Editor, 1981, pp. 225 - 229.