Marsden Hartley

American, 1877-1943

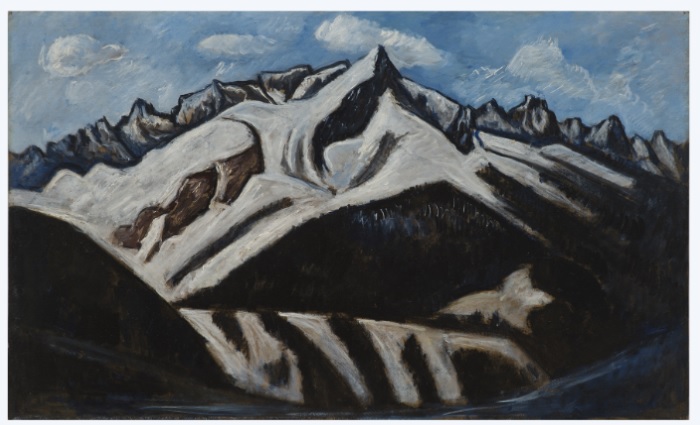

Alpspitz-Mittenwald Road, 1933-34

oil on paper board

18 5/8 x 29 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Sterling Morton to the Preston Morton Collection

1960.61

Alfred Stieglitz, "Marsden Hartley", 1916, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

“I am not a ‘book of the month’ artist and do not paint pretty pictures; but when I am no longer here my name will register forever in the history of American Art and so that’s something too.” - Marsden Hartley

COMMENTS

... Hartley continued his wandering—to Berlin in the 1930s, painting in Italy, France, and Mexico, and back to southern Germany for the last time, where he painted our Alpspitz-Mittenwald Road, an iconic Marsden Hartley. It could have been painted by no other. We feel the certainty of his brush strokes, the clarity of his personal vision, the incorporation of modernism with the geometric fragmentation of the image, the flattening and reconstruction of the landscape, the expressionistic distortion of color and light. He said, ''I want to paint the livingness of appearances.'' And it is that very livingness that grabs us—the muscularity, the sense of portraiture, the essence of the mountain, its power projecting to-ward us out of the clouds.

- Ricki Morse, "La Muse", December, 2020

American painter and writer. He spent part of his youth in Cleveland, OH, where in 1896 he studied art with a local painter, John Semon (1852–1917). After study at the Cleveland School of Art (1898–9), he entered the Chase School in New York (1899) and the National Academy of Design (1900–04). From 1900 he regularly spent his summers in Maine, a state for which he maintained an enduring passion. At the end of autumn 1907 he moved from Maine to Boston, MA. By this stage his painting was progressing from an American form of Impressionism to a type of Neo-Impressionism. Partly inspired by illustrations in the German satirical magazine "Jugend", he emulated the divisionist technique of Giovanni Segantini, for example in "Mountain Lake in the Autumn" (1908; Washington, DC, Phillips Col.).

In Boston, Hartley saw the Post-Impressionist work of Maurice Prendergast, who encouraged him and shared his enthusiasm for the art of Paul Cézanne. Hartley moved in spring of 1909 to New York, where he mixed in avant-garde circles, and in May he had a one-man exhibition at the 291 gallery, run by Alfred Stieglitz. Stieglitz’s support and tastes had a great impact on his development, but the immediate influence on sombre landscapes such as the "Dark Mountain" (1909; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.) was the art of Albert Pinkham Ryder.

Inspired by the introduction to European modernism that Stieglitz gave him in 1912, Hartley went to live in Paris, where he became friends with Gertrude Stein. The earliest of his paintings in Paris reveal his interest in Cézanne, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, whose work he had seen at Stein’s home. The bright colours and decorative patterned fabrics employed in some of his still-lifes reflect the influence of Matisse’s work. However, he soon became increasingly involved with his new discoveries: mysticism, the art of Vasily Kandinsky, and primitive objects illustrated in the almanac "Der Blaue Reiter".

Hartley was very interested in the theories and work of Kandinsky, whom he met on travelling to Germany in 1913, along with Franz Marc and other avant-garde artists. Although Hartley celebrated pre-war military pageantry in Berlin, he rejected the Futurists’ admiration of military force in favour of pacifist Native American themes, which he depicted in "Indian Fantasy" (1914; Raleigh, NC, Mus. A.). He also enjoyed the city’s homosexual subculture, falling in love with a Prussian officer, whose death he memorialized in 1914 in a series of emblematic abstractions influenced by Synthetic Cubism, including "Portrait of a German Officer" (New York, Met).

Forced by the war to return to the USA, Hartley lived a peripatetic existence. During summer 1916 he worked in Provincetown on Cape Cod, MA, where he produced geometric abstractions based on sailboat motifs, for example "Movement No. 9" (1916; Minneapolis, MN, Walker A. Cent.). In winter 1916–17 he stayed in Bermuda. From then until his return to Europe in 1921 he worked in Maine, New York, New Mexico, and Gloucester, MA. During this period he abandoned abstraction and returned to landscape and still-life. He briefly experimented with painting on glass in 1917 and from 1918 produced a series of pastels and oil paintings of the New Mexico landscape, for example "Landscape, New Mexico" (1919–20; New York, Whitney). From 1925 to 1929 he painted in the south of France, basing himself at Vence and Aix-en-Provence, where he emulated the work of Cézanne in studies such as "Trees and Rocks" (silverpoint on prepared paper, 1927; Ann Arbor, U. MI, Mus. A.).

In the 1930s Hartley painted in Mexico, Bavaria, Gloucester, Bermuda, and Nova Scotia, before returning in 1937 to Maine, where, except for stays in New York, he lived and worked for the rest of his life. He began an important series of expressionist memory portraits in 1938, including "Adelard the Drowned, Master of the Phantom" (1938–9; Minneapolis, U. MN, A. Mus.) on the island of Vinalhaven, ME, and continued to develop his interest in the figure. His attachment to nature, and in particular to the Maine landscape and seascape, inspired many of his late works, such as "Mountain Katahdin" (1942; Washington, DC, N.G.A).

Recent scholarship by Donna Cassidy recasts the painter’s identity from the ‘archetypal modern artist, romantic and mystical’— and apolitical—into one who integrated political perceptions into his artistic visions. Earlier beliefs about Hartley include a 1992 biography by Townsend Ludington, who notes that the artist ‘would have called himself apolitical’. This despite reporting how Hartley was pleased by ‘Aryan faces’, wanted to meet Adolf Hitler through his friends Erna and Ernst Hanfstaengl (both Nazi party members and longtime Hitler supporters), and wrote to a friend that Hitler just wanted to accomplish ‘the restoration of his people to their rightful place’.

Scrutinizing Hartley’s return home to Maine, Cassidy reinterprets a group of portraits and figures that had challenged scholars. Some scholars, notably Jonathan Weinberg and Bruce Robertson, related the muscular men of these late pictures to Hartley’s homosexuality; an interpretation that convinces yet does not exhaust. From the 1910s, Hartley had come to appreciate in German culture its emphasis on the classical male body as the masculine ideal, which met his wish to see the male as the object of homosexual desire.

In the late 1930s, Hartley had responded to a widespread demand for Americanism by staging his own nativist rebirth as a ‘Yankee artist’. He participated in the effort among leading cultural figures to define what constituted American art. Yet, during his stay in Bavaria during 1933–4, Hartley found attractive not only the mountain landscapes, but also the spectacle of Nazi parades and propaganda. The Nazis’ appropriation of the German fold played on his own early interest in German peasant genre painting and Bavarian folk art. This German experience, then, infers Cassidy, led him to treat his subjects back home as the ‘North Atlantic folk’. Among her telling examples is the central fisherman in Hartley’s canvas, "Down East Young Blades" (c. 1940; Kansas City, MO, Nelson– Atkins Mus. A.), who sports both an Alpine hat and a typical Bavarian folk jacket. Harley thus found in the rural North Atlantic region—that is, Maine and Nova Scotia—a new folk to embody the ‘ideal antimodern’.

Hartley’s male nudes connect with anti-puritan attitudes in the avant-garde circle of Stieglitz (who exhibited nude photographs of his wife, Georgia O’Keeffe) and with homoerotic strains in both European and American culture. One can view Hartley’s stalwart male bathers in the context of German cults of nudism and vitalism, which arose from Friedrich Nietzsche’s stress on the importance of reconnecting with nature. Nudism also linked up with anti-Semitism and encompassed eugenics and racial hygiene into its ideology, as exemplified in a Nazi film by Leni Riefenstahl.

This revised view of Hartley shows that he blended into one vision the homoerotic, the ‘primitive Other’ of the folk, and an ideal of racial purity. Cassidy argues that the racist content in Hartley’s painting of the North Atlantic folk has been occluded by the focus on their homoeroticism, when they actually embody ‘overlapping categories’.

Paradoxically, Hartley benefited from a number of Jewish supporters besides Stieglitz and Stein, including the critic Paul Rosenfeld, the art dealer Edith Halpert, and the artist Florine Stettheimer, who refused to see him after 1934 because of his recent stay in Germany, which she viewed as condoning Hitler and his policies. Hartley even wrote to Halpert from Germany, taking a vastly different tone from that he used with his non-Jewish friends. He asked her help to find a teaching position at a private school or ‘A Jewish institutes’.

Such disconnects, always disturbing, shock even more when we see how Hartley integrated his prejudices into his artistic programme. Hartley’s art and life, however, hold important lessons about the value of studying art in cultural context and the danger of the self censorship that kept earlier generations of Americans from studying Nazi art and recognizing these uncomfortable links.

- Gail Levin, Grove Art Online, 2014

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This is one of a series of paintings produced by Hartley during the most fecund periods of his late career. A highly experimental artist, who traveled extensively in France and Germany, Hartley brought all the avant-garde lessons of the previous twenty years to bear, achieving a truly original pictorial idiom. Like Cézanne and his mountain in the South of France, Hartley strove to capture the specific character of the mountains he studied in the Swiss Alps. The simplification of forms, calligraphic contouring, and overall unfinish attest to Hartley’s allegiance to a rigorous modernism that is as much indebted to German Expressionism as it is to the legacy of Cézanne and his emulators, including the Swiss Symbolist, Ferdinand Hodler.

- Highlights of American Art, 2020

This is one of a series of paintings produced by Hartley during one of the most fecund periods of his late career. A highly experimental artist, who traveled extensively in France and Germany, Hartley brought all the avant-garde lessons of the previous twenty years to bear, achieving a truly original pictorial idiom. Like Cézanne and his mountain in the South of France, Hartley strove to capture the specific character of the mountains he studied in the Swiss Alps. The simplification of forms, calligraphic contouring, and overall unfinish attest to Hartley’s allegiance to a rigorous modernism that is as much indebted to German Expressionism, as it is to the legacy of Cézanne and his emulators, including the Swiss Symbolist, Ferdinand Hodler.

- Let It Snow, 2018