Christian Gullager

Danish, 1759-1826 (active USA)

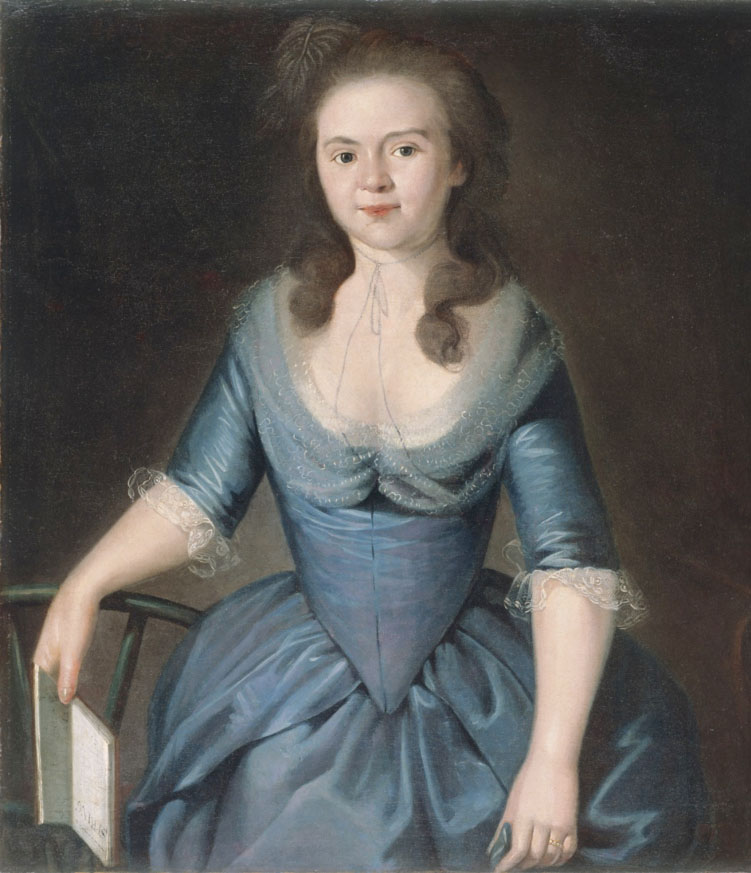

Elizabeth Coats Greenleaf, 1787 ca.

oil on canvas

36 1/2 × 32 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Sterling Morton for the Preston Morton Collection

1960.59

“Nothing in a portrait is a matter of indifference. Gesture, grimace, clothing, décor, even – all must combine to realize a character.” – Charles Baudelaire

RESEARCH PAPER

This engaging image of Elizabeth Coats Greenleaf was one of Christian Gullager’s first American portraits, commissioned by the Coats family in 1787 in the wealthy town of Newburyport, Massachusetts. She was the only daughter of a substantial middle class Newburyport ship captain. Typical of portraits of that period, she is featured bust-length displaying her face, upper body, and hands. Perhaps Elizabeth’s delightful, but restrained smile betrays the excitement she cannot contain of having her portrait painted. Portraiture was a coveted representation of position and wealth.

Danish painter Christian Gullager immigrated to America in 1786, from his native Denmark. He had studied at The Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen where he was awarded a silver medal in 1780. The twenty one year old Elizabeth Coats Greenleaf looks like a princess in her elegant blue dress with sleeves edged in white lace. Gullager’s handling of paint captures the luster of her gown and the illusion of sheer lace. The artist’s precise attention to costume details as well as his signature zigzagging brushstrokes that define highlights on her sleeves and bodice are stylistic attributes evident in his paintings throughout his career. The highlights exaggerate a frontal light source and he leaves the background dark without any detail. There is minimal use of color except for the emphatic blue of Elizabeth’s gown that dominates the composition.

In the American colonies social distinctions were expressed through the quality of clothes that one wore. Hence Elizabeth’s gown received far more attention in execution than her hands or face. The blue satin gown broadcast that Elizabeth was a woman of refined taste and wealth. The costly color blue alone was associated with majesty.

Elizabeth appears uncomfortable in a stilted frontal pose that lacks a sense of natural grace. It appears that Gullager may have physically positioned Elizabeth’s arms, hands, head and body. He also introduced visual metaphors, props that would communicate her dignified position in society. That may explain why she awkwardly holds an open book, in her right hand, so that the word “spring” can be seen written on it. Holding the book suggests that Elizabeth is an educated woman, with purpose, in keeping with the 18th century idea that intellect equaled a person of high position and fortune. The word “spring” is a reference to her youth and the luxury of being in a position to enjoy it. The feather decorating her beautifully coifed hair and the expensive fabric of her gown place emphasis on her carefree and implied extravagant life. Another indicator of a secure prosperous future is the engagement ring that she wears on her wedding ring finger. She would soon be married to John Greenleaf.

There are some other notable and important stylistic details of Elizabeth Coats Greenleaf’s portrait. The background of the painting is left neutral with no images that identify the sitter’s status. Often background elements were carefully selected to display the identity and prestige of the sitter. Elizabeth’s head is oversized for her body. Her hands and arms are painted with no attention to underlying bone structure and are also overly large. These stylistic attributes were typical of provincial Danish portrait style as well as of some American primitive portraiture that was popular in New England at this time. Both reflected how a growing ambitious middle class wanted to be portrayed with social identities characteristic of nobility. Simply put, they made status claims through their relationship to goods such as their attire and other props in their portraits.

There is evidence that suggests that Gullager may have struggled in completing the five portraits commissioned in Newburyport. It is evident that several portraits had pencil under-drawings, and many changes are visible as pentimenti, or corrections made during his process of painting. Although both the American primitive and the provincial Danish styles were similar in that they generally depicted neutral backgrounds, unsophisticated representations of anatomy, and the inclusion of objects symbolic of prosperity, Gullager may have made some adjustments more acceptable to his New England clients.

It was the good fortune of Christian Gullager to be part of a generation of painters at the time of the formation of the Republic. The rapid growth in commerce led to a great demand for portraiture by wealthy merchants, powerful lawyers, and members of a colonial elite who wanted their portraits to mirror their materialistic interests, power, authority and self confidence. There was also a need for paintings of important historical figures, and in this arena artists were seen as performing a noble art. The recording of permanent historical persons and events raised the status of the artist immensely.

In 1789 Gullager moved to Boston where he lived until 1797 and where he built a fine reputation; he was referred to as “one of the best portrait painters of this metropolis” by The Massachusetts Centinel. In Boston Gullager painted many wealthy distinguished Americans. Nearly sixty portraits are attributed to him, the most important being that of President George Washington. An interesting anecdote relates how Gullager sat in a church pew behind the pulpit and put great effort into drawing George Washington who was sitting in front of him attending the service. Later Gullager followed Washington to Portsmouth where he obtained a two hour sitting to make his portrait. Most interestingly, George Washington made a notation in his Diary recording this sitting.

Colonial portrait painters were caught up in a swirling consumer economy. Gullager had to craft portraits that he knew eighteenth century Americans would buy. This demanded changes in the composition and content of his paintings so as to better serve the tastes of the consumers. While in Newburyport his provincial Danish style was acceptable, the Bostonians were interested in different visual symbols to define them. They wanted their portraits to reflect their extravagant lifestyle, clothing, and elevated position in society the same way that European aristocrats did in the Rococo painting style. Gullager adopted the Rococo style of Carl Gustaf Pilo, once the director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and a portrait painter of the royal court. Gullager indulged his sitters, placing them in lavish and elaborately ostentatious, detailed rich clothing. He presented them as graceful, fanciful, erotic, and playful persons and painted in energetic, opulent, colorful, bright pastels.

However, the Rococo style was short lived due to the emerging values of the newly formed Republic. The new democratic government embraced Neoclassicism as the preeminent style because of its connection with democratic societies of ancient Rome and Greece. So Gullager adjusted the presentation of his sitters in keeping with this national political taste. He especially emulated the Neoclassic painter, Gilbert Stuart. Where the Rococo style had placed importance on a sitter’s individual extravagance now the Neoclassic placed more emphasis on an individual’s stately moral character. The desire for the sitter to claim elite status and identity, proclaimed through dress and setting, did not really change in the Neoclassic style. It was more the sitter’s image that was refashioned. The sitter needed to be perceived as a dignified person of good moral character, an idealized individual who had a pragmatic outlook, an egalitarian spirit, and a quiet self confidence. So Gullager placed his sitters in a less colorful, more orderly, uncluttered, more solemn, symmetrical space with emphasis placed on the centrally placed head.

It is important to note that throughout all of Gullager’s stylistic adjustments certain skills and brushstrokes remained. As seen in Elizabeth Coats Greenleaf’s portrait his zigzagging brushstrokes and defining highlights are evident in many of his paintings. Furthermore he was consistently proficient in presenting refined detailing of objects and fabric. Notice how the eye is drawn in these American midcentury portraits not to faces, but to the clothing that the people wore. However poorly a painter presented a sitter’s physical features, he almost always managed to capture the brilliance and luster of the clothes. “As much of commercial evidence suggests, the most important article among the British exports to eighteenth-century America—in terms of value as well as bulk—was cloth. The customs records reveal that approximately half of all colonial imports consisted of textiles. Social distinctions were expressed through the quality of clothes one wore.” (Ellen G. Miles) Americans were still concerned that these portraits presented a visual elite identity through the depiction of fashion. That is why the central element in these paintings may have been the sitter’s clothes.

Gullager was very active in his career. He established a drawing academy at his house on Tremont Hill in Boston. He painted scenery for the theater in Boston and New York, and designed engravings, medals, decorations for public and private buildings, and for publications and paintings on silk for Military Standards, flags, and drums. However in 1806 his life took a turn for the worse. He was fired from jobs painting stage sets due to his inability to complete work on time and exhibiting indolent behavior. Gullager’s indolence contributed to family troubles as well. In 1809 his wife, with whom he had fathered nine children, was granted a divorce. The last twenty years of his life are undocumented except for his return in 1826 to his granddaughter’s home in Philadelphia where he died.

Prepared by Gretel Rothrock for the SBMA Docent Council, 2018.

Bibliography

Barker, Virgil. “ American Painting: History and Interpretation”. New York: Macmillan Press.

Dresser, Louisa. “Christian Gullager, an introduction of his life and some representative examples of his work”. Springfield, Mass. Pond-Ekberg Co.

Dunlap, William. “History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States”. New York: Dover Publications.

Gerdts, William H. “Art Across America, Two Centuries of Regional Painting, 1710-1920”. New York: Abbeville Press.

Finlay,Victoria. “The Brilliant History of Color in Art”. Los Angeles: Getty Publications

Massachusetts Centinel, Boston, Nov 14, 1789

Mead, Katherine H. “The Preston Morton Collection of American Art”. SBMA Docent Library.

Miles, G. Ellen. “The Portrait in Eighteenth-Century America”. Newark: University of Delaware Press

Sadik, Marvin. “Christian Gullager: Portrait Painter to Federal America”. Washington D.C. National Portrait Gallery: Hathi Trust Print.

Washington, George. “Diary, November 3, 1789”. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit.

COMMENTS

Gullager [Guldager], (Amandus) Christian (b. Copenhagen, 1 March 1759; d. Philadelphia, PA, 12 Nov 1826). American painter of Danish birth. Gullager studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where he was awarded a silver medal in 1780. His earliest known portrait, of his great aunt or grandmother, "Mrs. Bodel Saugaard Acke" (Denmark, priv. col.), is dated 1782. He is next recorded on 9 May 1786, when he married Mary Selman in Newburyport, MA. The portraits he painted in 1787 portray Newburyport residents and, like "Mrs. Acke", are rendered in a Danish provincial style that suggests that he rejected the Neo-classical manner current in his homeland. Gullager moved to Boston by 1789, when he advertised his Hanover Street portrait studio, and worked diligently to establish a local reputation.

Gullager's most important early portrait was of "George Washington" (Boston, MA Hist. Soc.), who sat for the artist in Boston in October 1789 and again in Portsmouth, NH, that November. His portraits in the Rococo style from the 1790s suggest the influence of the Swedish painter Carl Gustav Pilo, whose work had been popular in Denmark during Gullager's student days. Gullager opened a studio in New York in the autumn of 1797 but moved the following year to Philadelphia, where he remained until at least 1805. After that he apparently lived in New York and may have tried his hand at scene painting.

- Carrie Rebora, in The Dictionary of Art, Jane Turner, Ed., v. 13 p. 842, Macmillan Publishers Limited, London, 1996

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This portrait is one of a group of three, commissioned by the Coats family of Newburyport, Connecticut in around 1787. It is one of the earliest examples of Gullager's portraiture in America, the artist having relocated from his native Denmark by 1786. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, awarded the young artist a silver medal in 1780, a clear harbinger of his artistic potential. He would spend the next decades as a sought-after portraitist, active in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

This likeness was probably done just before Elizabeth's marriage to John Greenleaf on November 2, 1791, and presents the twenty-something-year-old bride-to-be as a fashionably dressed, winsome young woman. When considered alongside the more static and proper portraits of her parents, the artist's intent to emphasize Elizabeth's relative youth and vivacity becomes more pronounced. She stands as if just having entered the room, a book with the word "spring" visible at the open page, a clear allusion to her youthful innocence. While her parents present themselves as sober, upstanding members of the middle class, a smile plays along Elizabeth's full lips and lurks at the corners of her sparkling eyes.

- Crosscurrents, 2018