Adolph Gottlieb

American, 1903-1974

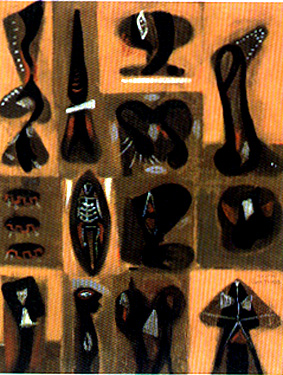

Composition, 1947

oil on canvas

32 × 25 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. Burt Kleiner

1959.77

Portrait of Gottlieb by Hans Namuth, 1962, (Published May 1963, ARTnews Collection, New York City, ©Estate of Hans Namuth)

RESEARCH PAPER

Adolph Gottlieb, a co-founder and member of the first generation of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism was born in New York City in 1903, and died at Easthampton, Long Island, New York in 1974 after a successful and critically acclaimed career. From 1920 to 1923 he studied at a number of art schools in New York and Paris. At the Art Students’ League in New York he worked with John Sloan and Robert Henri, former practitioners of the Ashcan school. After another period of travel and study in Europe, he attended Parsons School of Design, the Art Students’ League, Cooper Union and the Educational Alliance Art School. After teaching arts and crafts in New York, he worked in the Federal WPA Easel Painting Project, commencing in 1936. He was a founder-member (with Mark Rothko, Gatch and others) of The Ten in 1935 and exhibited annually. He was an active leader and articulate spokesman for numerous artists’ groups, championing their causes throughout his career. In 1958 he taught at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, and at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). Among his many awards was the Gran Premio, VII Bienal, Sao Paulo, Brazil. In 1967 he was appointed to the Art Commission of New York City. His work has been shown in more than 35 individual shows, and he is represented in over 35 of the important museum collections in the United States.

Composition, 1947, created in the year indicated, is one of some 500 Pictographs painted by Gottlieb during a ten-year period. The large rectangular canvas (32 inches high by 25 inches wide) is divided into a smaller series of grids or compartments that are formed from alternating colors of salmon and a muted brown. Set within each of the compartments is an irregularly shaped abstract form (often biomorphic) executed in a combination of intense black brush strokes and browns, and usually containing small areas of color, such as white, gray and orange.

Composition was a gift of Mr. Burt Kleiner to the Santa Barbara Museum on December 14, 1959. Prior to that it had been in the Bertha Schaefer Gallery, New York, the New Gallery (now Eugene V. Thaw Gallery) New York, and finally in the Paul Kantor Gallery, Beverly Hills.

Composition 1947 was painted by the artist during the earliest of three main Abstract Expressionist phases in his life. The Pictograph series occupied Gottlieb for a period of ten years commencing in 1941. From 1951 to 1957 he was engaged in the Imaginary Landscapes series, and from 1957 until his death in 1974 with the Bursts. These descriptive titles were originated by him. During the period 1951-1957 he also did paintings in the series called Labyrinth and the Unstill Lifes series. Gottlieb was a leader of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism and his work placed him within the sub-school variously called the myth seekers, the color-field painters and the chromatic abstractionists. In his later Bursts series, he combined the ideas of both the color-field painters and the action-gesture painters into an abstract symbolism.

Gottlieb’s early training in New York, Paris and elsewhere in Europe exposed him to traditional schools of European and American painters. He was especially attracted to modern European art as a result of his studies, reading, and viewing. John Sloan and Milton Avery strongly influenced him. Working under Sloan, he utilized limited colors and had a predilection for earth tones. He also was influenced by the soft color used by Milton Avery, who was a great admirer of Matisse’s colors. Gottlieb’s early work was figurative, and during the thirties he began to paint in a mildly Expressionist style. He had earlier rejected the prevailing styles of his youth, such as the patriotic regionalism of Benton, Wood and Curry, as well as Social Realism and its related left-wing political activism.

Gottlieb was interested in abstraction as a mode of expression. As his interest in what he would later call “emotional truth” increased, his concern and interest in the representation of physical reality decreased. The arrival in New York in the ’thirties of the Surrealists and artists interested in geometric forms (Mondrian), the interpretations of the theories of Freud and Jung, and the discovery by him of African Art and other primitive Indian arts all contributed to his philosophical and artistic development.

Shortly before and later during his sojourn in Arizona in 1937-1939, he began to compose simple still lifes, in broad, flat planes, with little modulation of tone, and he altered and abstracted them according to his imagination. The space was flattened and reduced, the palette was limited, and in Arizona he was using earth tones.

After returning from Arizona, he recognized that the New York painters were seemingly painting with a feeling of absolute desperation, and that the situation was so bad that he felt free to try anything. Rejecting Cubism and Surrealism, in part because of their European origin, which he concluded was not exportable, he and Rothko decided to experiment with mythological themes. For them, mythic themes brought and linked together their desires to paint subjects that were on the one hand as “tragic and timeless” as what the creators of tribal and archaic art had done, and on the other as personal and derived from the unconscious as the work the Surrealists had done. Gottlieb said that he adopted the term “Pictograph” for his paintings out of a feeling of disdain for the accepted notions of what a painting should be. He said that to acquiesce in the prevailing conception of what constituted good painting meant the acceptance of an academic straitjacket, and that it was necessary for him to repudiate so-called good painting in order to be free to express what was visually true for him.

The American artists like Gottlieb, Rothko, Still, and Pollock found Jung’s theories of the collective unconscious more to their liking than those of Freud, which was behind much of the Surrealist creations. The Americans sought pictorial equivalents of universal experience, and appropriated ancient myths, symbols and signs. If these universally meaningful forms were buried in the subconscious, they invented the technique of “psychic automatism,” which allowed the subconscious to generate buried images. Thus, automatic painting was developed. Although literal symbols of Freudian dream images did not necessarily appeal to the members of the New York school, the more ambiguous, but equally sexually charged vocabulary of forms invented by Arp and Miro remained an inspirational source. These so-called biomorphic shapes (similar to biological forms) were important to Gottlieb. Similarly important were the pictographic imagery evoked by African, Oceanic and Eskimo masks, as well as Egyptian Hieroglyphs, American Indian petroglyphs, archaic writing and symbology and 14th century Italian predella panels. However, notwithstanding that it is impossible to ignore the affinity between such symbolism and the forms he used, he disclaimed any deliberate intention of literally incorporating such elements into his painting. It has been said, however, that his ambiguity as to his sources is undoubtedly in keeping with his intentions. In any event, as time went on his symbolism became more and more abstract, with a heavier application of paint, less linear, and with a greater hue or intensity of color.

Gottlieb’s Pictographs represented the evolution of a new technique. Without working from nature or from preliminary sketches he would first lay down a grid, and the use of the grid provided him with a formula for his compositions for over 15 years. Then by using a process of intuition and free association, symbolism would be selected to fill the compartments in the grid. The grid offered Gottlieb several alternatives: His symbols could be placed neatly within some or all of the compartments shaped by the intersecting verticals and horizontals, the forms could spill out over the structure or they could imply an awareness of the grid without its actual use.

His use of grids probably was evolved from a variety of sources. Gottlieb expressed his admiration for Italian predella paintings of religious narratives in which episodes are arranged in boxes. He was also aware of the Cubist grid paintings of Torres-Garcia, and Mondrian’a geometric grids. It has been said that Gottlieb’s use of the grid is significant in the light of a suggestion that the grid’s status as the “Quintessential modernist emblem” rests on its potential to act as myth, and the grid functions in a mythical capacity to repress certain essential conflicts. Gottlieb apparently intuitively understood the ability of the grid to suspend conflict. The use of the grid also was used as a device to kill space or the illusion created by traditional vanishing point perspective.

In his later Imaginary Landscapes he abandoned the grid structure and reduced the associative aspects of the symbols but retained the juxtaposition of rounded and linear shapes where the picture surface was horizontally divided into a land mass and a sky punctuated with astral forms. The Bursts, his last series of paintings, have solar orbs suspended over turbulent ground masses, with colors reduced to a few basic hues, and indicate a sense of continuity in the evolution of Gottlieb’s work.

Written by Leslie E. Still - March 1983

Prepared for the Web Site by Terri Pagels- February, 2004

Selected Bibliography

Books:

Hunter, Sam, American Art of the Twentieth Century: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1974)

Rose, Barbara, American Art Since 1900: Revised and expanded Edition (New York, Praeger Publishers, 1975) see index.

Sandler, Irving, The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (New York: Harper & Row, 1976)

Ulanov, Barry, The Two Worlds of American Art, The Private and the Popular (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1965)

Periodicals:

Berger, M., “Pictograph into Burst, Adolph Gottlieb and the Structure of Myth”, Arts Magazine, Vol. 55, March 1981, pp 134-139

Butcher, G. M., “Gottlieb and the New York School”, Art News and Review, Vol 11, June 20, 1959, p9

Wilkin, Karen, “Adolph Gottlieb: The Pictographs”, Art International, Vol 41, Dec. 1977, pp 17-33Exhibition and Collection Catalogs:

Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, “The Fifties, Aspects of Painting in New York”, 1980

Joslyn Art Museum, “Adolph Gottlieb, Paintings, 1921-1956”, 1980 Omaha, Nebraska

David and Alfred Smart Gallery: co-sponsored by the Committee on “

Social Thought and the Department of Art of the University of Chicago: “Abstract Expressionism: A Tribute to Harold Rosenberg”, 1979

Sierra Nevada Museum of Art, “The New York School, 1940-1969, The First Generation of Abstract Expressionism”, 1979

Walker Art Center, “Adolph Gottlieb”, 1963

Whitney Museum of American Art, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, “Adolph Gottlieb” 1968