Gunther Gerzso

Mexican, 1915-2000

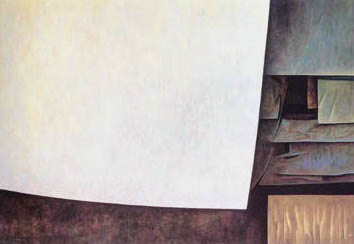

Le Temps Mange la Vie (El tiempo se come a la vida), 1961

oil on Masonite

17 ¾ x 25 ½ in.

SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by Jon B. and Lillian Lovelace, Eli and Leatrice Luria, The Grace Jones Richardson Trust, an Anonymous Donor, Lord and Lady Ridley-Tree, SBMA Modern and Contemporary Art Acquisition Fund, the Ala Story Fund, and the SBMA Visionaries

2002.50

Self-Portrait of Gerzso, 1945

"I want to paint constructions of the mind whose light calls out equally to one’s feeling and one’s intelligence." - Gunther Gerzso

“Many people say I’m an abstract painter. Actually, I think my paintings are more realistic. They are real because they accurately express what my life is about and in so doing, deal with everybody else, up to a point.” - Gunther Gerzso

RESEARCH PAPER

Gunther Gerzso was born in Mexico to European parents. His father passed away when he was only six months old. He grow up in both Americas and Europe mastering five languages (English, Spanish, German, French and Italian). While working for his uncle who was an influential German art dealer and collector and attending school in Switzerland (late 1920s), he became well versed in Old Masters and Modern European art. During this time he met Paul Klee and lived among his uncle's collection of paintings which included works by Pierre Bonnard, Rembrandt, Cezanne and many others. He also met Nando Tamberlani noted set designer, who would introduce him to the world of theater. On his return to Mexico in early 1930s, the perception that he was an outsider partly because of his Hungarian name was reinforced. To counter this perception, Gerzso explored his Mexican heritage.

Inspired by Charles Baudelaire poem entitled L’Ennemi (The Enemy) time is the “enemy” and using abstraction, Gerzso captures the poem’s theme of Human mortality.

“О grief! О grief! Time eats away life,

And the dark Enemy who gnaws the heart

Grows and thrives on the blood we lose.”

The poem’s literary presentation of watery graves and psychic depths are presented in a visual quiet and dramatic composition by Gerzso. A poetic metaphor for the universal drama of order and chaos as the undercurrent of man’s social and emotional development. This visual presentation is the artist’s attempt to exemplify an entry portal to the mystery of the world (shown by dark negative spaces) similar to when the primitive cultures entered the underground caves to conduct their rituals or myths.

Allowing a large and single plane of consistent composition emphasized in a light color dominates the canvas, while balancing smaller and varied textual planes and colors to coexist and being protected while guiding the viewer’s gaze to the inner lower layers. Small interlocking and overlapping squares and rectangles are repeated in a non-uniform pattern while creating an overall balanced and a rhythmic composition. The Cubist style and his fascination with massive blocks of stones from Tihuanacu civilization ruins, became the foundation of how a constellation of fragments can suggest forgotten ruins and landscapes within layers of time and space. This mixture evokes and emulates the relationship of macrocosm and microcosm and variety of energies and tensions that continuously and forever are at play.

In early 1930s, his career as a set designer in the world of film and theater brought him in close working contacts with the German immigrant community of Mexico, ties which mirrored his close connections with Surrealist artist exiles he had befriended. With his linguistic abilities and direct access to a creative group of people both in Mexico and United States, placed him in the center of the international and growing film industry in Mexico and provided a successful career in Mexican film industry, yet he suffered a perceived view of not being and an artist. While working as a set designer, he focused on his own private paintings.

After five years as a set designer at the Cleveland Play House and specific aim to launch a painting career, he returned to Mexico in January 1941. The Mexican Muralism was still at its height embraced by the post-revolutionary Mexican government. Gerzso was a pioneer of post-Muralist generation with his poetic form of abstract paintings having arrived late to the Surrealism, but early to Abstraction in Mexico. Being between these two schools contributed to him being both the vanguard and at the margins of modernism.

The artists known as “La Rapture” dominated the galleries in 1950s-60s exploring the themes of Mexican history and Revolutionary visions and the cosmopolitan and international trends of post-World War II toward subjectivity and abstraction, with Gerszo’s work being the symbolic bridge connecting to the La Rapture. The group’s common value of art autonomy inspired by Geszo’s independent and freethinking abstraction was their meeting point.

Prior to search for individual identity in Mexico, he had delved into Pre-Columbian art and architecture; a spirit of mystery about lost and forgotten civilizations capable of great design, engineering and construction with a sense of melancholy for the rural disregard and subsequent disappearance of these great cultures. Artist Wolfgang Paalen described Gerzso’s paintings as “a reverberation of ancient glories and new promises,” noting that, in painting Estela, “The timeless presence of Mayan monuments is not merely remembered but brought into a visionary focus.” This philosophy is present and center in many of Gerzso’s work.

He noted his Tihuanacu painting, 1950, was the decisive moment for his future work and style by having developed a visual language representing architecture structures and time periods in a layering format. It signaled a shift from biomorphic to architectonic abstraction using Cubism and its variants. In other words, he reinvented European sources by grounding them into a Mexican context.

Starting in Mid 1960s, he used the Golden Ratio (Greeks, 6th century B.C.) to structure and plan his paintings. Using mixing methods of the Old Masters and employing modern materials such as Duco (as a primer), and applying red paint as an under layer with extensive use of glazing, created vibrancy and translucency to his paintings. An in-depth analysis of the subject painting shows use of the reverse or smooth side of the masonite board for his work’s support, he carefully treated the surface of the wood panel to achieve a porcelain like final effect.

Gerzso had two basic formative influences. The first was his Cleveland period, when he sought a channel for his vocation as a painter at the same time that he was developing his career as a set designer. The second was his interpretation of post-Revolutionary Mexican art, which he made before forming a relationship with the European Surrealists living in Mexico.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Soheyla Valleie, 2025

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gunther Gerzso. Chicago Art Institute. Retrieved January 29, 2025. https://www.artic.edu/artists/34634/gunther-gerzso

SBMA Publication (2003). “Risking the Abstract: Mexican Modernism and the Art of Gunther Gerzso”

POSTSCRIPT

The Enemy by Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1821-1867) French poet

My youth was one long, dismal storm, shot through

Now and again with flashing suns; the rain

And thunder stripped my orchard bare: too few,

Today, the ruddy fruits that still remain.

And so I reach the autumn of my mind:

With rake and shovel must I now set out

To right the sodden landscape, where I find

Deep, gaping holes, like graves, dug roundabout.

But who knows if this soil, like sea-washed shore,

Will feed the new-dreamt flowers of my art

The mystic food their vigor hungers for?

-Ah woe! Ah woe! Time eats life to the core,

And the dark Enemy who gnaws our heart

Gluts on our blood and prospers all the more.

L’Ennemi

Ma jeunesse ne fur qu’un ténébreux orage,

Traversé çà et là par de brillants soleils;

Le tonnerre et la pluie ont fait un tel ravage,

Qu’il reste en mon jardin bien peu de fruits vermeils.

Voilà que j’ai touché l’automne des idées,

Et qu’il faut employer la pelle et les râteaux

Pour rassembler à neuf les terres inondées,

Où l’eau creuse des trous grands comme des tombeaux.

Et qui sait si les fleurs nouvelles que je rêve

Trouveront dans ce sol lave comme une grève

Le mystique aliment qui ferait leur vigueur?

---O douleur! ô douleur! Le Temps mange la vie,

Et l’obscur Ennemi qui nous ronge le cœur

Du sang que nous perdons croît et se fortifie!

From: Selected Poems from Les Fleurs du mal: A Bilingual Edition

By Charles Baudelaire

Translated by Norman R. Shapiro

COMMENTS

GERZSO'S PROCESS: RECONCILIATION BETWEEN REASON AND IMAGINATION

Technique and process are two other areas where analysis proves a connection between Gerzso’s work and Abstract Expressionism. For the Abstract Expressionists. spontaneity was of the highest aesthetic value. Having embraced Surrealisms concept of psychic automatism, they believed in a creative process that was direct and immediate. Pollock's drip paintings epitomize their idea of "alla prima", in which the artist works freely on an unprepared canvas, responding to impulse as opposed to Following a structured plan. By placing his canvas on the floor instead of the easel and using unconventional tools instead of traditional artist's brushes, Pollock represented Abstract Expressionism's "culture of spontaneity”. Yet, Pollock's method was also purposeful and deliberate, the perfect example of control as much as abandon. Writes Michael Leja, “Pollock was committed both to painting from the unconscious and to outdoing Picasso and others in the making of sophisticated, structured, modernist paintings.“

Gerzso, too, believed in spontaneity, but balanced with deliberation. His creative processes as well as his architectonic structure at once reveal his rational and imaginative approach to art making. Having been educated in Europe, at the side of his uncle who demanded of him a connoisseur’s eye, Gerzso was well versed in European Old Master technique. As he developed his own form of expressive abstraction, this foundational knowledge became central. An entire shelf in Gerzso's still intact studio is filled with texts on painting technique, many devoted to the Old Masters, including Max Doerner’s "The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting with Notes on the Techniques of the Old Masters" (1934), Jacques Maroger's "The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters" (1948), Frederic Taubes's "The Mastery of Oil Painting" (1955), and Daniel Thomson’s "The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting" (1956). In addition, Gerzso had monographs on many of the major European Old Master painters, among them Bosch, Brueghel, Canaletto, Piero della Francesca, Tintoretto, and Titian, as well as specialized publications on fifteenth-century Flemish painting.

Gerzso's astonishing craftsmanship was an innate gift and the result of his self-education. Gerzso never attended art school; his surprising technique was realized in ten years of solitary labor. While he was not a formal student of art, Gerzso consistently shared technical notes with other painters, among them Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Otto Butterlin. Like Gerzso at the beginning, Butterlin was a painter after hours and on the weekends, having a full-time job as a chemist with the Bayer Company in Mexico. As a chemist, Butterlin offered Gerzso insights into the physical properties of paint and paint processes. “I learned the ‘abc’s’ of painting here in Mexico," said Gerzso, “with several friends who were painter-enthusiasts.” Through the years, one continues educating oneself and discovering new secrets.

Of the European Old Masters, it was the Northern Renaissance painters, especially members of the Flemish School, who most interested Gerzso. His immersion in this aspect of art history came through his Wolfflin-trained uncle, who researched and published on the Swiss fifteenth-century painter Konrad Witz (ca. 1400). Born in Germany but active in Switzerland, Witz became that country's most important Renaissance painter, and his meticulous naturalism suggested that he was aware of his Flemish contemporaries Jan Van Eyck and Master Flemalle. His most famous surviving work, the St. Peter Altarpiece, in the Cathedral in Geneva, now in the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Geneva, helps explain the highly refined application of paint and the extremely smooth, porcelain-like surfaces of Gerzso‘s fully mature works. One of Gerzso’s earliest observers made this association: “He paints in a technique which rivals the Van Eycks.” Gerzso’s passion for oil painting is another point that confirms this link to Witz, Van Eyck, and the Northern Renaissance tradition, because it was Van Eyck's innovations in oil painting that helped transform this medium into a dominant mode for serious artists beginning in the sixteenth century. To satisfy his taste for precisely rendered subjects and obsessively worked surfaces, Gerzso hung in his living room a view of Rome by the Venetian oil painter Ippolito Caffi (l809-1866) and in his studio a reproduction of a Flemish oil painting.

During the 1930s and 1940s, artists in both the United States and Europe developed a renewed fascination with oil painting and the “secrets” of the Old Masters. Out of this fresh look at tradition came two of the most influential publications on the subject, both of which Gerzso owned, Doerner's The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting with Notes on the Techniques of the Old Masters (1934) and Maroger's The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters (1948). A pioneering arttist-chemist from Frankfurt, Doerner was especially influential in the German-speaking countries of Europe, which explains one way that Gerzso would have been introduced to his book, in addition to the fact that it was the “Bible” for artists of the period. Gerzso also spent many an hour conversing about Old Master techniques with his Surrealist cohorts Varo and Carrington.

Together Doerner’s and Maroger’s publications led to a revival of tempera painting and experiments with "mixed" techniques, notably egg-oil emulsions as underpainting followed by oil resin glazes. Having the ambition to look like but not necessarily be like the Old Masters, modern painters, like Salvador Dali and Otto Dix, experimented with secrets of the past but with new materials that were more scientifically sound. Alluding to historical painting while using innovations in materials science, Gerzso, too, synthesized new expressive means with Old Master techniques.

Serving as a case study, Gerzso’s "Le temps mange la vie" ("Time Eats Away Life"), 1961, exemplifies the artist's technique for creating his expressive abstractions of the 1960s. Using the reverse or the smooth side of masonite for this work’s support, Gerzso carefully treated its surface in order to emulate the historical process of painting on wood panel, which can yield porcelain-like surfaces. Combined with a highly refined surface texture, this quality of smoothness, “so smooth that it appears to have been painted on fine silk," became a hallmark of Gerzso’s fully mature work. Conservation analysis of this work revealed that Gerzso used the traditional painting process of priming the support, but he did so with Duco, a modern substitute for the classic gesso. It also showed that he applied a conventional under layer but that he experimented by using a brilliant red. While Italian Old Masters would have also used a colored ground, they would not have selected the vibrant red employed by Gerzso. State-of-the art conservation analysis also determined Gerzso’s extensive use of glazing. One of the defining characteristics of Gerzso's fully mature painting is its mesmerizing luminosity, which he achieved through the application of traditional glazing techniques. Like Renaissance painters, Gerzso built up layers of thin transparent colors with little or no admixture of white, which allowed light to be reflected back from the prepared ground and from the successive layers of colors. Yielding a different type of color and light than does the mixing of pigments, glazing imparts a special depth and radiance. Since recession was a tactical aspect of Gerzso’s expressive abstraction, he frequently used this Old Master process, which was slow and painstaking compared to the swift and spontaneous methods of the Abstract Expressionists.

Showing an affinity for the “mixed” techniques used by the Old Masters and promoted by Doerner, Gerzso combined pastel with oil paint in Le temps manage la vie, but unlike the Old Masters, he experimented with a fixative in order to adhere it to the surface. Old Masters would not have risked this process for fear of losing the pastels brilliant color, but by using modern materials, Gerzso found a way to bind the medium without compromising its rich hue. In this blending, he capitalized on creating contrasts between matte and shiny surfaces in the way he characteristically contrasted smooth and textured surfaces. These contrasts aid in creating the illusion of mysterious, shifting depths, as did Gerzso’s use of scumbling, an Old Master technique in which a thin, opaque layer of paint is applied over dark underpainting.

- Diana C. Du Pont, "Gunther Gerzso, 1915-2000", Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2003, pp. 147-149

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Gerzso was born in Mexico to a Hungarian-Jewish father and a mother from Berlin, Germany. As a teenager, he studied in Switzerland and lived with his maternal uncle, an art dealer in Lugano. Between 1935 and 1941, he designed sets for the Cleveland Play House in Ohio. He went on to art direct more than 150 films in the Mexican film industry between 1943 and 1962.

In this painting, planes of color float and overlap in a shallow space. Could the large white rectangle be a stage or a huge curtain waiting to be lifted to reveal a drama? Will the colored planes on the right suddenly move to reveal an actor? The poet Octavio Paz described Gerzso’s work as “painting at the halfway point of time, suspended over the abyss . . . painting-before-the-event. Before-what-is-going-to-happen.”

- Going Global, 2022

The work of Gunther Gerzso explores the facets of human existence, often engaging abstractly with concepts of eternity and the unknown. No work better epitomizes this philosophical preoccupation better than Le Temps mange la vie/El tiempo se come a la vida. The title of this work comes from a poem by Charles Baudelaire entitled “L’Enemmi” (The Enemy) from his most famous work, Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), in which time is the enemy that slowly eats away at life.

- SBMA title card, 2013