Jean-Leon Gerome

French, 1824-1904

Head of Tanagra, 1890 ca.

polychromed marble

21 1/2 x 11 x 9 in. (object with base)

SBMA, Museum purchase, European Deaccessioning Fund

1993.9

This bronze bust, completed by French artist J. B. Carpeaux around 1871 and acquired by the SBMA in 1997, forcefully captures the keen inquisitiveness of his friend and fellow artist in Portrait of Gérôme (Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Robert J. Emmons).

RESEARCH PAPER

The Head of Tanagra by Jean-Leon Gérôme is a bust in polychrome marble delicately colored in the style of ancient Greece. This piece is one of a series done by the artist, which was inspired by the colored terracotta figurines excavated at Tanagra during the 1870s.

Painter, sculptor and teacher, Gérôme, considered one of the most prominent late 19th century academic artists in France, began his devotion to sculpture in the last 25 years of his life. As a painter, his historical and mythological compositions were considered anecdotal, painstaking, often melodramatic, and frequently erotic. As a teacher at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he counted among his many pupils Odilon Redon and the American artist Thomas Eakins. That he became a sculptor at the age of fifty-four is a surprising fact in itself. Still more astonishing, his most important work in the new medium dates from 1890 or later. As a painter, Gerome had specialized in scenes of daily life in ancient Greece and Rome, rendering with minute realism and archaeological precision; in his sculpture, he retained this allegiance to the ancient world, but with unexpectedly original results. He applied life-like tints to his marbles and liked to combine a variety of materials, knowing that the ancients had done so.

Obviously Gerome received his first impulse to start a career as a sculptor from his own strong plastic sense, a feeling for structure, shape and volume that had been apparent since his earliest paintings. It is said that a threatened weakening of his eyesight had more or less to do with Gerome's adoption of his new avocation, or perhaps he was beset with the restlessness so often found in large natures for new worlds to conquer.

But another impetus may have been the series of discoveries in the 1870s of the many small statuettes of the Hellenistic period, the famous Tanagra figurines of Boeotia, located in central Greece, 12 miles east of Thebes. These genre figures of great skill, brightly painted, were a late but absolute justification of his work as a Neo-Grecian painter.

The Tanagra figures were also an encouragement to bring realism to sculpture through polychromy. In 1890 Gerome exhibited a marble, delicately tinted, of Tanagra a life-size seated nude, holding in her left hand a gaudily painted Tanagra figure of a hoop dancer. One is not privy to which came first, but the bust in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art collection appears to be done at the same period as the life-size nude, which is now in storage at the Louvre. (2005 update: currently on view at Musee d’Orsay)

The inspiration for these pieces was the large cache of terracotta figurines, which bore traces of their original blue and pink patina, which were widely imitated in their own time, with Tanagra work spanning the period from about 340 to 150 B.C. The finest examples from the late 4th and 3rd centuries compare favorably with the life-sized work of the great masters of classical Greece, which they not infrequently imitated.

The figures were first discovered in graves, and dealers who had obtained them from grave robbers offered them for sale in Athens. The Albanian inhabitants of the area had practiced grave robbing in the neighborhood of ancient Tanagra sporadically from at least as early as the beginning of the 19th century. In accordance with the prevailing custom in classical antiquity, the dead of Tanagra were buried outside the city walls beside the principal roads leading out of the city. The excavations of the 1870s and later were for the most part illicit; and, where official, were badly conducted. The factories where the figurines were made still await excavation, with the rest of the city.

The first Hellenistic Tanagras appeared for sale in 1872 and a number were acquired for the Louvre by the archaeologist and collector Olivier Rayet. The British Museum and the Staatliche Museum of Berlin then entered the field and later the Russian Ambassador to Greece, P.A. Sabouroff, formed a first-class collection, which he sold in 1884 to the Hermitage Museum of St. Petersburg. As the demand began exceeding the supply, the dealers were reduced to producing forgeries from the fragments in their possession. Those interested in learning more about the Tanagra figurines should read Reynold Higgins' book, Tanagra and the Figurines (1). Those who are prepared to read scholarly works in German are referred to the books by Canarache and Kleiner. Both contain many interesting black and while photographs showing the great variety of different types of these figurines, which have been unearthed (2).

Michelangelo, certainly one of the greatest carvers of marble, explained carving as “knocking away the waste material to reveal the figure within the stone”. This Tanagra head emerges as a portrait of a Greek patrician matron as it would have appeared in ancient times. It is of Carrara marble, mounted on a base of polished variegated white, brown and gold marble. The bust itself is covered with a thin wash and then delicately tinted in pastel shades. The hair is finely delineated with masterstrokes in a style popular at the time -- a loose coil at the top, and the front with a part in the middle and marcelled waves on either side. Befitting her station, the woman does not appear to wear cosmetics, with only a slight pink tinge to her lips and no darkening of brows or eyelashes. She has beautiful blue-grey eyes and lovely ears. Interestingly, she has a small curl next to only one ear. Her expression echoes that of the enigmatic Archaic smile famous in ancient Greek statues. The skin tones are so lifelike that she might take a breath at any moment, especially since there is a slight sheen in the indentations of the collarbone and on her upper lip. Gerome has captured and enhanced this lovely Hellenistic woman.

When it was acquired by the Museum in 1993, the bust's surface was generally soiled and efforts were made not to disturb the pigment when conservation was performed. The surface was minimally cleaned with the aid of a microscope and using a plastic eraser reduced lighter soiling of the flesh tone areas. The work is signed by the artist on the right edge of the bust.

In his later years, Gerome lost favor with the public because of his position against the avant-garde of Manet and the Impressionists. People were successfully made to feel embarrassed if they enjoyed or admired his works. When he died in 1904, after a career that must be described as distinguished, there was no memorial to him. We cannot as yet describe accurately his place in the history of art for the true history of late 19th century art in which he would fit has not been written. But those who see the bust can but admire his genius.

In 1899 Theodore Reinach wrote in a French periodical '...the Tanagra lady is truly the Parisienne of Antiquity.'

NOTES

1 Higgins, Reynold. Tanagr a and th he Figurines. Princeton University Press, 1986.

2 Canarache, V. Masken and Tanagra-Figuren aus Werkstatten yon Callatis - Mangalia. Archaologisches Museum Konstanze, 1969

Kleiner, Gerhard, Tanagrafiguren: Untersuchungen Zur Hellenistischen Kunst and Geschichete. Walter De Gruyter, Berlin, 1984.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackerman, Gerald M. The Life and Work of Jean-Leon Gerome: with a Catalogue Raisonne. Sotheby's by P. Wilson Publishing, London, 1986

Janson, H. W. 19th Century Sculpture. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1985, pp. 191-192

Mills, John W. The Technique of Sculpture. Van Nostrad Reinhold Co., New York, 1965, Chapter 2, pp. 18-35

Shinn, Earl. Gerome A Collection of the Works of J. L. Gerome in One Hundred Photogravuers. Samuel L. Hall, New York, 1881

The Dayton Art Institute, "Jean-Leon Gerome", Nov. 10-Dec. 30, 1972, pp. 12-15, 93-95.

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th Edition, Volume 5, pp. 221, 1994 (Gerome, Jean-Leon).

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th Edition, Volume 11, pp. 535, 1994, (Tanagra)

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Terry David, March, 1995

Enhanced for the web by Loree Gold August 2005

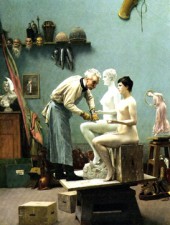

Jean-Leon Gérôme, Working in Marble or The Artist Sculpting Tanagra (Le Travail du marbre or L'Artiste sculptant Tanagra),1890, Oil on canvas, 19'/ x 159/6 in. (50.5 x 39.5 cm), Dahesh Museum, 1995.104

COMMENTS

This complex self-portrait is a summation of Gérôme's remarkable career as both painter and sculptor. It is also a commemoration of his famous sculpture entitled Tanagra, 1890 (Musee d'Orsay, Paris), a nude personification of the ancient Greek city, who holds one of the small painted figurines that bestowed renown on the artisans of that city. Inspired by these figurines as well as by his own quest for realism, Gérôme delicately tinted the skin, hair, lips, and nipples of his marble, causing a sensation at the Salon of 1890. Like most 19th-century sculptors, he did not carve the marble himself but furnished professional marble cutters with a full-size plaster to use as a guide. It is this intermediate step that is depicted in Working in Marble, a title that refers to the overall creative process. Gerome portrays himself on a turn stand putting the finishing touches on the plaster version of Tanagra, carefully judging the accuracy of his work against the live model. He is in his second-floor painting studio (which could not have housed an unfinished marble of that size), described by a contemporary as a "splendid room, with its great sculptures and paintings, some still unfinished, and a famous collection of barbaric arms and costumes." Indeed, this painting includes many of these props-quiver, saddle, armor, drums, waterpipes, flag, textiles, masks used regularly by Gerome to enhance the authenticity of his Orientalist and classical scenes. It also contains several of his finished works: the Tanagra-inspired HoopDancer; Selene the moon goddess; and, most notably, his painting Pygmalion and Galatea. This latter image depicting marble transformed into flesh provides a mythological gloss on Gerome's own activity in Working in Marble, powerfully evoking the continuous interplay among painting and sculpture, reality and artifice, as well as the inherently theatrical nature of the artist's studio.

Transcribed from Highlights from the Dahesh Museum Collection

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In 1878, at the age of fifty-four, the successful academic painter Gérôme took up sculpture. This

marble head depicts a female personification of Tanagra, a small village in Boetia, where, in

1870, excavations unearthed a set of terracotta figurines. These figurines were considered an

exciting affirmation of the practice of polychromy (painting or tinting) in ancient Greek and

Roman sculpture. Gérôme’s enthusiasm for the practice resulted in figures like this one, in which

the gleaming marble is given a disturbing realism through the coloring of the hair, eyes, and lips.

This head of Tanagra relates to a full-length seated figure holding a painted figurine in the style

of the excavated terracottas, completed by the artist in 1890.

- Ridley-Tree Reopening, 2021

This piece attests to a heated period of experimentation in the painter-turned-sculptor Gérôme’s studio in the 1890s: the coloring of a life-size, white marble figure personifying the ancient Greek city of Tanagra, a center once famed for its polychrome statuettes. This hand-tinted marble bust was a prelude to the artist’s subsequent exploration in colorofto of the full figure in three dimensions. Its rough, broken peripheries, create a jarring effect when juxtaposed with the seeming lifelikeness of its tinted flesh, triggering an uncanny viewing experience: as in a horror film, this dismembered fragment still palpitates with life.

- Sculptures that Tell Stories, 2019