Charles Garabedian

American, 1923-2016

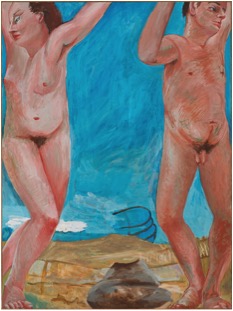

Prehistoric Figures, 1978-1980

acrylic on board

40 x 30 in.

SBMA, Gift of Thomas and John Solomon in memory of Holly Solomon

2014.94

COMMENTS

SANTA BARBARA -- Thirty years ago, Charles Garabedian first showed his gorgeous suite of nine panel-paintings called "Prehistoric Figures" as the culmination of a San Diego museum survey of his career. They haven't been seen together again since 1984's Venice Biennale.

The paintings, most long since dispersed into public and private collections, have now been reunited for "Charles Garabedian: A Retrospective," which opened last week at the Museum of Art here. Even if the rest of the show were not so engrossing -- and it is -- they would be worth the trip to Santa Barbara on their own.

When first shown it was hard to know quite what to make of them. One or two male or female nudes are shown in each, occupying relatively barren landscapes.

The figures twist, turn, tumble and even fall, their arms akimbo and often reaching toward the panel's edge, as if trying to grab some aesthetic stability there. Unlike the similarly configured bodies in Robert Longo's ultra-chic "Men in the Cities" drawings, begun the year after Garabedian started his series, stylish high drama is not their focus.

Garabedian's figures are pushed to the foreground and their faces are placid, betraying no sense of anguish, ecstasy or despair. The landscape's horizon line is low, making the nudes feel monumental, even though each panel is only 40 inches high. And the bright cerulean sky unfurled behind them seems massive -- wide open and filled with limitless possibility.

Skulls and bones turn up here and there, unpretentious signs of mortality. But, as nudes unencumbered by style-dated fashion, they betray no particular time or place. Prehistoric, they nod toward future narratives, whether factual or fictional, by which people make sense of living.

And as figurative paintings dating to a period (they were painted between 1978 and 1980) when once-triumphant Modern abstraction was exhausted and painting as a worthwhile practice had even been declared dead, they insist: Not so fast! The "Prehistoric Figures" are little manifestos extolling the irrepressible power of imagination. And imagination is an unruly thing -- impractical, vivifying, a hedge against mortality and just plain fun.

At the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the suite turns up in the show's second room, rather than near the end as in Garabedian's last full-scale retrospective, where they first saw public daylight. Curator Julie Joyce has whittled down his early work to about a dozen examples, and decided to draw from work done since 1963-– five years earlier than the start date for paintings shown in San Diego.

Both decisions were wise. Garabedian was a late bloomer as an artist. His quirky and circuitous experiments prior to the mid-1970s mostly demonstrate his inexhaustible inquisitiveness -- before that trait became the very subject of the pivotal "Prehistoric Figures." The current show is weighted toward what came after.

Its 61 paintings on wood, canvas, resin and paper show him forming a distinctive visual language -- and then hitting his stride. Together with a fine catalog, whose only drawback is unreliable color in the reproductions (they're far too red), it secures his place among the best painters Los Angeles has produced.

Garabedian, 87, was born in Detroit, the youngest of three children, to parents who had fled the Armenian genocide. His mother died when he was 2. His father, seriously injured shortly afterward in an automobile accident, was forced to place the siblings in an orphanage. At 10, with the Great Depression deeply entrenched, the boy and his family moved to California.

Garabedian didn't pick up a paintbrush until he was 32, a decade after service in World War II. He spent time in Mexico looking at murals by Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, eventually went to graduate school at UCLA and was nearly 40 when he began to exhibit. His first solo show at Ceeje Gallery in West Hollywood took place in 1963, the same year Andy Warhol's Elvis paintings had their public debut at Ferus, two blocks down La Cienega Boulevard.

The first fully mature work in the retrospective is 1975's "Chinese Mr. Hyde" -- a big, beautiful yellow head, like a luminous sun marked with jittery abstract lines and cloud-like smudges of paint. They suggest a cross between facial features and graffiti scratched on urban walls.

The character of Mr. Hyde comes from a distinctly modern literary source -- Robert Louis Stevenson's "strange case" of sharply conflicting personality traits, both lodged within a single psyche. Here the imaginative fracas is dislocated to China -- an ancient civilization halfway around the world, and one known to Americans (including Garabedian) mostly as a litany of equally strange stereotypes and cliches.

"Chinese Mr. Hyde" is a marvelous repudiation of several bromides then coming into art-world contention, including ideas of aesthetic purity, linear progress in art's development and claims made for the relative merits of certain media. Garabedian's paintings brush them all aside, instead hanging their hat on expanding the liberating power of imagination.

His works draw on myriad precedents. Some are artistic -- Matisse's brash color, Fra Angelico's Renaissance modesty, Picasso's stylized multiple viewpoints, Diebenkorn's fluid abstraction, the Mexican muralists' epic monumentality and more.

Others are literary. In addition to Stevenson, there's Homer's "Iliad" and "Odyssey," the Roman histories of Herodotus and Ovid's "Metamorphoses." Garabedian doesn't illustrate these stories. Instead he reconfigures them, coaxing imaginative contemplation into view.

Take Apollo and Daphne, rendered in countless ways by artists over centuries. In 2009, Garabedian dismantled the story and rebuilt the narrative from scratch.

In his hands the god and the nymph stretch out across the wide, horizontal sheet of paper as sympathetic lovers, rather than as a belligerent pursuer and his frightened prey. (The shared pose recalls Paul Manship's sculpture "Prometheus" at Rockefeller Center, or Oskar Kokoschka's painting "The Tempest.") Golden Apollo is helpless, his side pierced by Eros' passion-tipped arrow. The ancient river god called for help by a benevolent Daphne floats by the couple on his back, symbol of aged wisdom in life's inevitable passage.

Bits of green laurel sprout between their bodies. The leaves signify Daphne's transformation into a laurel tree, as well as Apollo's resulting elevation of the laurel wreath as a victorious crown. But Ovid is nowhere in sight. Greek mythology is acknowledged, even esteemed -- and then laid quietly to rest. As a poetic evocation of the transformational power of love, rather than a violent tale of power and domination, Garabedian's metamorphosis is complete.

- Charles Garabedian: A Retrospective, 2011