Helen Frankenthaler

American, 1928-2011

Snow Pines, 2004

thirty-four color woodcut, ed. 51/65

37 1/4 × 26 in.

SBMA, Gift of Thomas and Janet Unterman

2016.28.2

Helen Frankenthaler, britannica.com

"There are no rules. That is how art is born, how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules. That is what invention is about." - Helen Frankenthaler

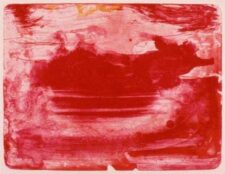

Helen Frankenthaler - The Red Sea, lithograph, 1978-1982

COMMENTS

Widely known for her iconic “soak-stain” canvases, acclaimed artist Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011) was an equally inventive printmaker who took risks in a medium not frequently explored by abstract expressionists. "Fluid Expressions: The Prints of Helen Frankenthaler", from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation highlights Frankenthaler’s often-overlooked, yet highly original print production.

Frankenthaler became well known through her large, almost 10-footwide oil painting, "Mountains and Sea", made in 1952. In a breakthrough development, she poured thinned oil paints onto raw, unprimed canvas to suggest the Nova Scotia landscape. With an element of chance, the inks bled into the bare cloth in a dramatic play of watercolor-like washes, instinctual shapes, and receding space. Her pioneering, immediate approach widened the practices of abstract expressionists and went on to inspire Color Field abstract painters such as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland and generations of future artists.

Frankenthaler made over 200 prints, and the earliest one in the exhibition is from 1968, executed during a printmaking revival in the U.S. that is still going strong. The exhibition includes almost 30 prints made from a diverse range of techniques, including lithography, etching, aquatint, screenprinting, pochoir, Mixografia, and woodcut. As an abstract expressionist, Frankenthaler championed a type of image that “looks as if it were born in a minute”—expressive, effortless, unstudied. However, printmaking presented technical and aesthetic challenges for the artist because it is an inherently controlled practice. The process can require many assistants, calculated chemical reactions, and long proofing processes that hinder artistic spontaneity. The artist’s adaptation of her “soak-stain” aesthetic for the graphic medium offers a stunning look at how printmaking—notorious for being a slow process—can exude a sense of immediacy.

From splattered pigments to translucent layers of colorful ink, the radiant prints brought together in "Fluid Expressions" pulse with creative energy. An innovator, Frankenthaler was interested in colors and the independent paths they took in both her paintings and prints. A collaborator with chance, she was intrigued with prints, and borrowed aspects of her painting technique to achieve her fluid style in the print medium. Just as she placed canvas on the floor in her studio, Frankenthaler sometimes installed the print matrix on the floor in order to work directly over its surface. She poured pools of greasy ink onto the heavy Bavarian stone in making her lithographs, going with the flow of the ink itself.

For instance, in a nod to her Jewish faith and the iconic biblical scene, Frankenthaler used tusche wash and crayon to create the sheer layers of ink in "The Red Sea", a lithograph from 1978–82. Her choice to print the edition on pale pink paper creates a visual play between the vibrant colors of the image and that of the paper support. Frankenthaler worked tirelessly to achieve this desired translucency and layering of color. The print went through twenty trial proofs, many with detailed annotations and drawings by the artist, before arriving at its final composition. The extensive proofs allowed Frankenthaler, a colorist at heart, to experiment with the subtle tonal variations from overprinting different color washes in different orders.

Unlike many print artists, Frankenthaler remained intimately involved throughout the print process: she chose the paper, mixed ink, approved registration, and even cut rigid woodblocks herself. Often made with dozens of colors, her woodcuts revived the medium in the 1970s. In the ukiyo-e style woodcut "Snow Pines", from 2004, Frankenthaler evokes the snowy greenery and verticality of a pine forest. The grain of the woodblock reinforces this woodland subject, and its vertical striations add to the towering sense of height. Yet while Frankenthaler’s energetic strokes of green and white color suggest a landscape of snow-dusted pines, there is ultimately nothing representational about her image. Indeed, many of Frankenthaler’s works recall the natural world through their abstracted forms and color palettes. The titles of her prints often reference the environments they conjure, yet her images are never explicit in their specific scenery. Frankenthaler preferred “to use nature but then dismiss it” as her creative source...

- Patricia Phagan, Fluid Expressions: The Prints of Helen Frankenthaler, Art at Vassar, Fall/Winter 2017/18, 3-4

https://fllac.vassar.edu/docs/art-at-vassar/FLLAC-Art-at-Vassar-2017-Fall.pdf

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

A celebrated artist from the second generation of Abstract Expressionists, Frankenthaler is most known for her large-scale gestural and abstract paintings. In the 1970s, she began experimenting with traditional Japanese woodblock printing techniques, learning to create the impression of delicate washes of color. Her process became defined by three key elements: visible grain, depth of blended color, and paper treatment. Throughout her long career, she continuously worked with collaborators to reinvent the woodcut, ultimately expanding the possibilities of the medium.

- In the Meanwhile, 2020