Helen Frankenthaler

American, 1928-2011

Green Sway, 1975

acrylic on canvas

92 x 92 in.

SBMA, Gift of ZHR Properties, LLC

2016.35

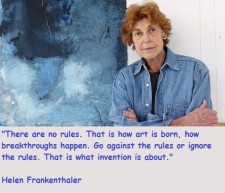

Photo of Frankenthaler at work in her studio at 83rd Street and Third Avenue, Manhattan, 1964, New York Magazine.

“One really beautiful wrist motion, that is synchronized with your head and heart, and you have it. It looks as if it were born in a minute.”

“You have to know how to use the accident, how to recognize it, how to control it, and ways to eliminate it so that the whole surface looks felt and born all at once.”

“We would sift through every inch of what it was that worked, or if it didn't, and wonder what was effective in it, in terms of paint, the subject matter, the size, the drawing.”

- Helen Frankenthaler

RESEARCH PAPER

Introduction

Helen Frankenthaler is one of the most improbable and authentic painters of the 20th century. Unlike most of the struggling European and American artists venturing into Abstract Expressionism in New York City following World War II, she was reared as the privileged daughter of a New York State Supreme Court Judge, sent to the best schools, studied with major artists like Rufino Tamayo and Hans Hoffman and attended Bennington College, an exclusive, highly experimental, work-enriched education which exposed her to the likes of Erich Fromm. Upon graduation she enrolled in Columbia for graduate work in Art History, to assure her family she was serious, but stopped going to class as her studio work demanded her attention.

Rigorously schooled in Cubism and the European development of Modernism from early high school at the Dalton School through college, she had so thoroughly incorporated Modernism into her understanding of art that she immediately began to push boundaries, in her words “letting the painting take me where it needs to go.”

Another boundary she pushed was that of the woman artist. She just never went there. She was an artist, period. She loved giving dinner parties for 100; she loved to dance and entertain, continuing to live the Upper East Side Manhattan life in which she had been reared, which was enhanced by her marriage in 1958 to Robert Motherwell (1915-1991), another second-generation Abstract Expressionist and the heir of a wealthy Manhattan family. They became society’s golden couple, each of them presented in major exhibitions, including Frankenthaler’s blockbuster retrospective at the Whitney in 1969.

In the macho world of Abstract Expressionism led by hard-drinking, womanizing individualists like Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) and Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), she was deeply influenced by Pollock’s drip paintings, particularly that he removed the canvas from the easel and put it on the floor and that he disrupted perspective by approaching the canvas from any side, not letting the edges of the canvas determine the evolution of the picture. In her friendship with Clement Greenberg (1909-1994), the leading voice of art criticism of the period, she also cut her own path. She was in her twenties, he twenty years older and the ruling art critic. Their affair lasted until 1955. In the meantime he introduced her to Pollock’s work, and she knew immediately that Pollock had broken through a boundary she had been pushing at. However, she rejected the label “action painting,” which Pollock identified with. She said she was basically influenced by Cubism, and that she was moving into what was happening next.

More Biographical Details

Born the third and youngest daughter to a prosperous New York State Supreme Court judge, she was reared to believe she could achieve whatever she set as her goals. Her father of Russian Jewish heritage and her mother of German descent promoted European cultural values, respecting education and steeping their daughters in the musical and artistic riches of Manhattan. Her schooling at the Dalton School, a private primary and secondary school on 89th Street, just north of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, provided an enriched environment for her, and encouraged her early interest in art. At Dalton, she studied with Rufino Tamayo, who lived nearby and had absented himself from the revolutionary chaos of Mexico to pursue his career in New York City. She respected and appreciated Tamayo, except when he made changes to her work on the work itself. She admonished him to use a separate piece of paper and not deface her work.

At Bennington, she was plunged into an in depth study of European Cubism and the other early explorations of modernism like Surrealism, Italian Futurism and automatism, that off-shoot of psychoanalysis which held that the artist could free himself from his cognitive mind and allow his unconscious to draw lines and produce images derived from the unconscious mind.

As she began to work in her own studio, her early works were Cubist, denying perspective in the picture by layering different views of the object upon one another in such a way as to reveal a different experience of the object.

Very early in her career she found a unique way of expressing herself, in pouring paint directly onto an unprimed canvas. Her hallmark work, “Mountains and Sea,” was produced when she was only 24. By this time she had the attention of Clement Greenberg, the prevailing voice of authority in art criticism in New York, indeed in the art world. He introduced her to galleries, arranged exhibitions and most importantly introduced her to the major artists working at that time, primarily Jackson Pollock, whose work freed her from the easel and led to her saturated canvas, color field work which took Abstract Expressionism to its next revelation. Their affair lasted until 1955 and by all reports was a very civilized parting. Helen Frankenthaler was a very civilized person. Greenberg continued to champion her work the rest of his life.

When she was 30, in 1958, she married Robert Motherwell, thirteen years older, married twice before and one of the most well establish, educated and important Abstract Expressionists of the day. The son of an early president of Wells Fargo in San Francisco, he studied at Stanford, Harvard and Columbia and earned a Ph.D. in philosophy. He was the leading spokesman for automatism in New York and a widely collected artist. They became the golden couple of the Upper East Side in Manhattan, giving dinner parties for 100 and accepting White House invitations. When the Prince and Princess of Wales were entertained there, a man who had been dancing with Diana, the Princess, was directed to Helen’s table. Obviously the White House knew she loved to dance. She sailed into her studio the next morning jubilant. “I waited a lifetime for a dance like this,” Barbara Rose reports she said. Asked with whom, she said she didn’t know and offered his card to her assistant. The card read, John Travolta.

Her marriage to Motherwell ended without public comment in 1971, and it was clear that her life was little effected, as she had been aggressively pursuing her studio work throughout their marriage, while entertaining and enjoying life in Manhattan as she always had. A note, which is completely my conjecture: in 1977 she completed a compelling work with a dark background and elusive lights on the surface. Asked about it by E. A. Carmean, “M,” says the artist, “both celebrates and tenderly cherishes a nostalgic feeling for a specific life. It’s a mourning, and an homage, of sorts.” (Carmean, p.74).

She continued to work in various studios, particularly on the Connecticut coast in the summer, and to travel extensively in Europe. We can immerse ourselves in her experiences through her powerful, huge canvases, which pull us directly into her experiential world. And in 1994, when she was 66, she married Stephen DuBrul, a man her own age, an investment banker originally from Michigan via Norte Dame, who had excelled in devoting his skills in the service of the U.S. government and various international mnon-profits. They lived in a gracious, traditional house on the Connecticut coast in Darien where she died in 2011. Stephen DuBrul died the following week.

Visual Analysis of the Work

My first sense is of the green and its power to move the other elements in the picture. Next I am aware of the verticality of what seems to me to be landscape-like, in color and feeling. The verticality is emphasized not only by the canvas shape but more dramatically by the dark vertical lines on either side of the central mottled panel, as if we are pushed to the surface of the work, seeing the reflections of bouncing light. Next the splotches of warm brown, then the white of the raw canvas to the right and the white paint left of center add a glimmering light. The spring green color seems to exert pressure on the central neutral area, which upon examination is not so neutral but a very complexly worked surface containing yellow pools of light and the warm brown repeated. Now we notice the whimsical scarlet on the lower left, like a glance of something new.

We are aware of the demand of the surface on our attention, almost like we walked to the edge of a wood and squinted our eyes so that our only awareness was of the play of light and dark. As we stay with the presence of the surface we are more and more aware of an intentional playfulness, of the artist trying different colors and moods and balance to achieve the finished image, which feels as if made in a single instant, an impression, but with the pervasive truth of an actual moment.

Technique and Materials and Influences

In 1963 Frankenthaler switched from oil paints diluted with turpentine to water-based acrylic paints which had become available in the mid-1950s. These acrylic emulsions were very fast-drying and provided a wash effect similar to that of watercolor, which enhanced the color field effects of her technique. After seeing Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, she removed the canvas from the easel, put it on the floor and began to pour oil paints diluted with turpentine directly onto raw canvas. These early paintings often included halos of turpentine around the poured shapes and also did not age well, as the turpentine rotted the canvas over time. “. . . the acrylics simply provide her with a few convenient distinctions: new colors, greater luminosity and durability, a more immediate contact with the canvas, and more resonance at the contours and edges. In her hands the paint can be solid, impenetrable ground, soft wash or blot, air, a streak like spilled and hardened wax on the surface, “’light in light.’” (Berkson, p. 43) The acrylics provided more transparency as she swept, brushed and sponged the diluted paint over the surface of the work. Then she added drawn elements, lines and accent colors in a manner echoing Gorky and Kandinsky and harkening back to the automatic drawing influence of Miró.

“Frankenthaler’s accurate sense of the appropriate size for a picture as it is scaled to the observer ought to be noted here, since the areas we speak of are real in extent and not merely symbolic. Furthermore, in response to her history as an “action” painter after the manner of Jackson Pollock, one should recall that these pictures are ‘physically’ planned in the making and are not the product of sketches executed by the artist as workman. With the canvas thrown upon the floor, walked around and even into, when necessary, the arms, legs and bodily effort over at least sixty or seventy square feet of terrain preclude any mere projection of an ‘a priori’ concept. The physical realities are constantly under consideration. The difference between this procedure and that of the painter who works from sketches or from a pre-scheduled order, is like the difference between the architect who works in close cooperation with the individual site and the one who begins and ends with the drafting table.” (Goossen, p. 16) Frankenthaler describes her physical relationship to the subject matter of her work, “Mountains and Sea,” 1952. Following a trip to Nova Scotia she poured thinned paint onto canvas on the floor, “and I know the landscapes were in my arms as I did it.” (Carmean, p. 12)

Another innovation shared by many of these Post-Painterly Abstract Expressionists (Clement Greenberg favorite description of the second generation Abstract Expressionists) was the use of sail canvas rather than the traditional European linen. It was available in large sizes, suiting their tendency to make very large paintings, and it was much less expensive. Galleryists were expanding spaces to accommodate the larger canvases being produced by Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, to name a few of the Color Field painters.

In the 1970s she began to apply tape to the raw canvas, prior to the pour. “I used tape as drawing,” she recalls. “I created variations . . . where I bent the tape, allowing some seepage under it for softness of the edges. I knew how and where the tape and the tint might require softening.” “Beginning to cover the remaining surface with washes of varying colors of tint, the artist removed some of the tapes while the canvas was wet, allowing the paint to seep into the previously masked areas. In other portions, some of the remaining tape was removed and adjusted in response to the developing work. As with the initial tapes, when these were removed they left white canvas areas. These reserved passages were subsequently articulated with colors along their edges . . . “ (Carmean, p.68) E. A. Carmean (Director of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth) is referring here to another 1975 work called “Tulip Tint,” but I think upon close examination you will find these process descriptions apply to our “Green Sway.”

Frankenthaler’s Influence

The break-through painting, “Mountains and Sea,” 1952, roughly 7 x 10 feet, was heralded by Clement Greenberg as having changed Morris Louis’ entire direction, “his first sight of . . . an extraordinary painting done in 1952 by Helen Frankenthaler called ‘Mountains and Sea’ led Louis to change his direction abruptly.” (Carmean, p. 12) Frankenthaller loaned and then gave this painting to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

The terms “color field painting” and “lyrical abstraction” became current in dicscussing both Frankenthaler’s work and that of contemporaries Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis and later artists like Larry Poons. Robert Hughes notes that, “In the 1960’s and early 70’s, more museum time and space was devoted to color-field painting than to any other American movement or style.” (Hughes p. 548)

In assessing Frankenthaler’s power as an artist, he says, “The Pollock follower who picked up on this earliest was Helen Frankenthaler (b. 1928), in 1952. With a precocious picture called “Mountains and Sea.” An amalgam of Hans Hofmann (with whom she briefly studied), Kandinskyy, and Gorky, this landscape set the tone of her later work by conspicuously dissociating “painterliness” from heavy, impasted paint. From then on she worked with extremely dilute pigment, floated, washed and puddled on the absorbent ground. The results, like “Interior Landscape,” 1964, had at their best a burning immediacy of color all of whose elements hit the eye purely and straight off, with one hedonistic jolt.” (Hughes, p. 548)

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Ricki Morse, September 2014.

Bibliography

Berkson, Bill, ‘Poet of the Surface,’ “Arts Magazine,” May-June 1965.

Carmean, Jr, E. A, “Helen Frankenthaler: A Paintings Retrospective,” Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Abrams, New York, 1989.

Glueck, Grace, “Helen Frankenthaler, Abstract Painter Who Shaped a Movement, Dies at 83,” New York Times, December 27, 2011.

Goossen, E. C., “Helen Frankenthaler,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1969.

Hughes, Robert, “American Visions,” Knopf, New York, 1997

Rose, Barbara, “Frankenthaler,” Abrams, New York, 1969.

COMMENTS

Helen Frankenthaler, the lyrically abstract painter whose technique of staining pigment into raw canvas helped shape an influential art movement in the mid-20th century and who became one of the most admired artists of her generation, died on Tuesday at her home in Darien, Conn. She was 83.

Known as a second-generation Abstract Expressionist, Ms. Frankenthaler was married during the movement’s heyday to the painter Robert Motherwell, a leading first-generation member of the group. But she departed from the first generation’s romantic search for the “sublime” to pursue her own path.

Refining a technique, developed by Jackson Pollock, of pouring pigment directly onto canvas laid on the floor, Ms. Frankenthaler, heavily influencing the colorists Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, developed a method of painting best known as Color Field — although Clement Greenberg, the critic most identified with it, called it Post-Painterly Abstraction. Where Pollock had used enamel that rested on raw canvas like skin, Ms. Frankenthaler poured turpentine-thinned paint in watery washes onto the raw canvas so that it soaked into the fabric weave, becoming one with it.

Her staining method emphasized the flat surface over illusory depth, and it called attention to the very nature of paint on canvas, a concern of artists and critics at the time. It also brought a new, open airiness to the painted surface and was credited with releasing color from the gestural approach and romantic rhetoric of Abstract Expressionism.

Ms. Frankenthaler more or less stumbled on her stain technique, she said, first using it in creating “Mountains and Sea” (1952). Produced on her return to New York from a trip to Nova Scotia, the painting is a light-struck, diaphanous evocation of hills, rocks and water. Its delicate balance of drawing and painting, fresh washes of color (predominantly blues and pinks) and breakthrough technique have made it one of her best-known works.

“The landscapes were in my arms as I did it,” Ms. Frankenthaler told an interviewer. “I didn’t realize all that I was doing. I was trying to get at something — I didn’t know what until it was manifest.”

She later described the seemingly unfinished painting — which is on long-term loan to the National Gallery of Art in Washington — as “looking to many people like a large paint rag, casually accidental and incomplete.”

Despite the early acknowledgment of Ms. Frankenthaler’s achievement by Mr. Greenberg and by her fellow artists, wider recognition took some time. Her first major museum show, a retrospective of her 1950s work with a catalog by the critic and poet Frank O’Hara, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, was at the Jewish Museum in 1960. But she became better known to the art-going public after a major retrospective organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1969.

Although Ms. Frankenthaler rarely discussed the sources of her abstract imagery, it reflected her impressions of landscape, her meditations on personal experience and the pleasures of dealing with paint. Visually diverse, her paintings were never produced in “serial” themes like those of her Abstract Expressionist predecessors or her Color Field colleagues like Noland and Louis. She looked on each of her works as a separate exploration.

But “Mountains and Sea” did establish many of the traits that have informed her art from the beginning, the art historian E. A. Carmean Jr. suggested. In the catalog for his 1989-90 Frankenthaler retrospective at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, he cited the color washes, the dialogue between drawing and painting, the seemingly raw, unfinished look, and the “general theme of place” as characteristic of her work.

Critics have not unanimously praised Ms. Frankenthaler’s art. Some have seen it as thin in substance, uncontrolled in method, too sweet in color and too “poetic.” But it has been far more apt to garner admirers like the critic Barbara Rose, who wrote in 1972 of Ms. Frankenthaler’s gift for “the freedom, spontaneity, openness and complexity of an image, not exclusively of the studio or the mind, but explicitly and intimately tied to nature and human emotions.”

- Excerpted from Grace Glueck, "Helen Frankenthaler, Abstract Painter Who Shaped a Movement, Dies at 83", New York Times, December 27, 2011

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

The artist applied acrylic paint, thinned with water, with buckets, mops, and paintbrushes onto raw canvases as they lay on her studio floor. She stated that none of her paintings were planned and depended upon happy accidents through the painting process. For "Green Sway", she poured paint in thinned washes on a raw canvas and let them form color-drenched veils. Its vertical strokes of complementary tones—warm browns and varying greens—suggest trees or plant matter. The sense of undulating movement hints at nature’s seasonal transformations. At a time when women artists struggled in the male-dominated New York art world, Frankenthaler achieved enormous success. She is sometimes credited as the inventor of Color Field painting, a movement that prioritized areas of color over the emotive drips and marks of Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock.

- Contemporary Gallery Opening, 2021

Helen Frankenthaler is one of the pioneers of Color Field painting, a movement that emerged in the exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction, curated by influential critic Clement Greenberg at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1964. In Color Field painting, color takes precedence, covering the entire canvas, and is devoid of the gestural, emotive brushstrokes that typify Abstract Expressionism. Frankenthaler pioneered the “soak stain” method, in which pigment is diluted and applied to raw canvas, allowing the paint to soak into the fibers rather than rest on the surface. Suggestive of landscape painting, "Green Sway" uses color and light to evoke the tranquility of nature, while the watercolor-like painting effect provides a sense of immediacy and ephemerality.

- Contemporary to Modern, 2014