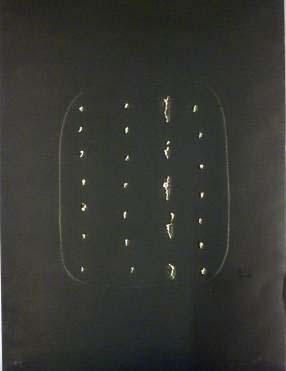

Lucio Fontana

Italian, 1899-1968 (active Argentina)

Concetto spaziale (Spatial Concept), 1968

embossed print, ed. 109/210

25 3/8 x 18 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Arthur and Yolanda Steinman

1985.50.24

Undated photo of Fontana

"I make holes, infinity passes through them, light passes through them, there is no need to paint"

- Lucio Fontana

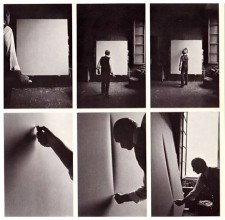

Fontana at work in his studio

COMMENTS

Lucio Fontana was an Italian painter, sculptor and theorist of Argentine birth. He moved with his family to Milan in 1905 but followed his father back to Buenos Aires in 1922 and there established his own sculpture studio in 1924. On settling again in Milan he trained from 1928 to 1930 at the Accademia di Brera, where he was taught by the sculptor Adolfo Wildt; Wildt’s devotion to the solemn and monumental plasticity of the Novecento Italiano group epitomized the qualities against which Fontana was to react in his own work. Fontana’s sculpture The Harpooner (gilded plaster, h. 1.73 m, 1934; Milan, Renzo Zavanella priv. col., see 1987 exh. cat., p. 118) is typical of his work of this period, with a dynamic nervousness in the thin shape of the weapon poised to deliver a final blow and in the coarse and formless plinth. Soon afterwards, together with other northern Italian artists such as Fausto Melotti, Fontana abandoned any lingering Novecento elements in favour of a strict and coherent form of abstraction. In 1934 he became a member of Abstraction–Création and went on to take part in the Corrente group’s exhibitions.

In his early abstractions Fontana took a middle course between painting and sculpture by producing plaster reliefs and free-standing but essentially planar works in plaster or iron, for example Abstract Sculpture (iron, h. 625 mm, 1934; Turin, Gal. Civ. A. Mod.), in which a meandering but generally straight-edged line of metal describes a single plane. Fontana at this time used both flat, geometrically regular shapes and organic biomorphic forms with undulating contours suggestive of enlarged cells. There are other ambiguities and apparent inconsistencies in his work of the late 1930s: alongside his search for a geometric perfection he also produced an extensive group of ceramics in which figures or objects are suggested in a fragmented and violently disturbed form that draws attention to the manipulation of the clay by his hand, and especially by his thumb. In works such as Horses (1938; Duisburg, Lehmbruck-Mus.), some of which he produced in 1937 at the Sèvres factory in Paris, Fontana displayed his sympathy with the Neo-Expressionist currents that were emerging in the major cities of Italy as a reaction against the retrospective spirit of the Novecento.

During World War II Fontana returned to Argentina, where in 1946 he founded the Academia Altamira with the artists Jorge Romero Brest and Jorge Larco; together they collaborated on the Manifiesto blanco (Buenos Aires, 1946). In this text, which Fontana did not sign but to which he actively contributed, he began to formulate the theories that he was to expand as Spazialismo, or Spatialism, in five manifestos from 1947 to 1952. He opted decisively for abstraction but hinted also at the need to take account of new techniques made possible by scientific progress. This text therefore marked the end for him not only of figurative art but also of a static, classical style of abstraction. He also questioned the traditional reliance in Western art on a flat support such as canvas or paper, proposing instead that the time had come for artists to work in three or rather four physical dimensions, since time also had to be added to the equation, in order to disturb the entire environment with their interventions.

Following his return to Italy in 1948 Fontana exhibited his first Spatial Environment (1949; Milan, Gal. Naviglio), which prefigured later international developments such as environmental art, performance art, land art and Arte Povera. This first temporary installation by Fontana consisted of a giant amoeba-like shape suspended in the void in a darkened room and bombarded by neon light, a material which was to be taken up by other artists in the 1960s. By their nature such works had an ephemeral life, but they were reconstructed for later exhibitions on the basis of documentary evidence provided by Fontana’s drawings, by photographs and by first-hand accounts. Fontana’s concern with environments led him also to collaborate in the early 1950s with the architect Luciano Baldessari on the design of several exhibition pavilions.

Fontana’s concept of Spazialismo, as formulated in the texts that he published on his return to Italy, was based on the principle that in our age matter should be transformed into energy in order to invade space in a dynamic form. He applied these theories to a feverish, violent, subversive and radical production in which he synthesized the various elements of his art. He devised the generic title Concetto spaziale (‘spatial concept’) for these works and used it for almost all his later paintings. These can be divided into broad categories: the Buchi (‘holes’), beginning in 1949, and the Tagli (‘slashes’), which he instituted in the mid-1950s. In both types of painting Fontana assaulted the heretofore sacrosanct surface of the canvas, either by making holes in it or by slashing it with sharp linear cuts.

The Buchi, such as Spatial Concept (oil on paper mounted on canvas, 790×790 mm, 1952; Paris, Pompidou), continue to exploit the beauty of chance and accident seen earlier in Fontana’s ceramics, and in this sense they bear comparison with other developments of the period such as Art informel, Tachism, Abstract Expressionism and action painting. In some works Fontana violated the surface not only by piercing it but by sticking irregularly shaped objects, such as bits of coloured glass, on the canvas in random configurations, as in Spatial Concept (1955). The Tagli, such as Spatial Concept—Expectations (1959; Paris, Mus. A. Mod. Ville Paris), are clearer and more concise in form, but they are also generally asymmetrically and casually arranged. However many cuts are made into the canvas, the surface as a whole remains intact and two-dimensional, and, for all their apparent violence, these pictures continue to be displayed as conventional easel paintings. They form an important part of Fontana’s contribution to Continuità, which the artist joined in 1961.

Fontana applied similar techniques to sculptures such as Spatial Concept (painted iron, diam. 3 m, 1952; Turin, Gal. Civ. A. Mod.). The most successful of these works are those in which the incisions are made into a lumpy surface that retains the delightfully irregular and unpredictable character of soft organic materials such as wax or chalk even when cast in bronze. Other sculptures are more decisively three-dimensional, as in the case of imperfect and randomly shaped spheres such as Nature (1959–60; Otterlo, Rijksmus Kröller-Müller), in which visible gashes suggest sexual orifices or eruptions of volcanic activity. In sculptures of this type Fontana not only completely freed himself from the tyranny of two dimensions but created a balance between the idea and its physical manifestation. Among Fontana’s last works are a series of Teatrini (‘little theatres’; e.g. 1965; Paris, Pompidou), in which he returned to an essentially flat idiom by using backcloths enclosed within wings resembling a frame; the reference to theatre emphasizes the act of looking, while in the foreground a series of irregular spheres or oscillating, wavy silhouettes creates a lively shadow play. He was awarded the Grand Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale of 1966.

Renato Barilli

From Grove Art Online

© 2009 Oxford University Press

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Fontana was born in Argentina to an Italian father, who carved funerary monuments, and an Argentine mother. Throughout his life, he traveled between the two countries. By the 1930s, he was not only a fervent advocate for abstract art in Italy and France but also an equally vociferous Fascist, designing sculptures for the party’s Milan headquarters. He returned to Argentina in 1940 but then moved to Milan in 1947 to found Spatialism. Around that time, he punctured the artwork’s surface and developed a practice based on cuts, folds, and deformations of the paper, which he believed could revivify art by making it concrete and actual. Fontana wrote in one of his manifestos that “The gesture [of attacking the artwork’s surface], once accomplished, lives for a second or a millennium, for we are convinced that, having accomplished it, it is eternal.”

- Going Global, 2022

Born in Rosario de Santa Fe, Argentina to Italian parents, Lucio Fontana spent much of his early years living in Milan. In 1922, he followed his father back to Buenos Aires to help with a commercial sculpture business. After spending much of the 1930s in Europe, the artist returned to Argentina in 1940 to escape World War II. Here, he began formulating his theories of Spazialismo (Spatialism) in the Manifesto blanco (White Manifesto), published in 1946. Keeping with the spirit of the new post-war age, Fontana proposed a “spatial” art that would challenge the illusory space of traditional easel painting by synthesizing color, sound, space, movement, and time. Upon returning to Milan in 1947, he further articulated these ideas in five manifestos published between 1947 and 1952.

In 1949, Fontana initiated his “Concetto spaziale” (Spatial Concept) series, puncturing or slashing the surface of paper or canvas. Punctures and slashes became his signature gesture— negating the flatness of the picture plane and opening up its sculptural possibilities. The artist pre-emtively wrote in 1948 “Art dies but is saved by gesture.”

- SBMA title card, 2013