Léonor Fini

Argentine, 1908-1996 (active France)

Dos bailadores (Two Dancers), 1930's ca.

ink on blue paper

12 1/8 x 9 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Margaret P. Mallory

1991.154.11

“Paintings, like dreams, have a life of their own and I have always painted very much the way I dream.”

“When a painting is finished I can perhaps consciously say that this is this or that is that, but the beginning for me is never an idea. It happens first as a color or a form. If I try to analyze afterwards what I have done, I feel as if I am cheating because I can never be sure. A painting is something like a spectacle, a theater piece in which each figure lives out her part.”

—Léonor Fini

POSTSCRIPT

“Had this been the 17th century”, George Melly wrote in his obituary of her, “Leonor Fini would have been burnt as a witch”. The imagery in her work attests to this. She was not the most talented, but the imagination was fertile and often wandered in an erotic direction, having much to draw on, as her love-life had been varied and unusual. (Among other texts, she illustrated de Sade’s ‘Justine’!) Her ethnic background was of mixed Spanish, Italian, Argentinian, and Slavic blood, a formidable genetic cocktail. Her primary inspiration, as she once said, was the ‘Theatre of her own Mind’.

http://whollybooks.wordpress.com/female-surrealists-women-in-touch-with-their-inner-witch/

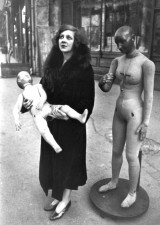

Léonor Fini, 1932, by Henri Cartier-Bresson

COMMENTS

Leonor Fini was born in Buenos Aires on August 30, 1907. She was raised in Trieste by her mother, and by her maternal relatives, the Brauns, who enjoyed deep ties to the Triestine intelligentsia, including Italo Svevo, Umberto Saba, and James Joyce.

A self-taught painter, she had no formal training in art. This explains the challenge of identifying her with a particular school of painting: her evolution, rather, was marked by her preferences and affinities, and reflected her own “imaginary museum.” She first showed her work at the age of 17, in a group exhibition in Trieste. Around the same time, during a trip to Milan, she met the painters Funi, Carra, and Tosi, and discovered the works of the schools of Ferrara and Lombardy, as well as those of the Italian mannerists.

A visit to Paris in 1930 convinced Leonor that her career would flourish there, and in 1931, she left her family in Trieste. The following year, she held her first solo exhibition, at the Galerie Bonjean, whose director was Christian Dior. Her circle of friends in Paris included Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Pieyre de Mandiargues, and Georges Bataille, as well as Max Jacob, Paul Éluard, and Max Ernst. Despite these associations, she never was a formal member of the Surrealist group.

She made her first trip to New York in 1936, showing at the Julian Levy Gallery and participating in the famous “Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. In 1939, for longtime family friend Leo Castelli, she organized at Paris’ Galerie René Drouin an exhibition of Surrealist furniture by artists including herself, Salvador Dali, Meret Oppeheim, and Max Ernst.

As the second World War approached, Leonor fled Paris with her friend Mandiargues. They spent part of the summer of 1939 as guests of Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington in Ardèche, before moving on to Arachon, where Salvador and Gali Dali were staying. Arriving in Monte Carlo in 1940, she began painting portraits, an activity she would continue into the early 1960s. Her favorites would prove to be those of her friends: Anna Magnani, Maria Felix, Suzanne Flon, André Pieyre de Mandiargues, Leonora Carrington, Meret Oppenheim, Jean Genet, Jacques Audiberti, Alberto Moravia, and Elsa Morante.

It was in Monte Carlo in 1941 that Leonor met Stanislao Lepri, the Italian Consul. With her encouragement, he became a painter, and the two moved to Rome shortly before the city’s liberation in 1943. Several years later, they returned together to what had been her home in Paris in the rue Payenne. A 1952 encounter with the Polish writer Constantin Jelenski, also known as Kot, proved definitive: he and Stanislao would remain the two great loves of Leonor’s life.

During the postwar years Leonor Fini became known to a wider public – both for her participation in costume balls, as well as for her theatrical work. This included creating sets and costumes for George Balanchine’s “Le Palais de Cristal” at the Paris Opera, Roland Petit’s “Les Demoiselles de la Nuit” at the Théâtre Marigny, “L’Enlèvement au Sérail,” at La Scala in Milan, as well as collaborations with Jean Mercure, Jacques Audiberti, Albert Camus, Jean Genet, and Jean Le Poulain.

In the summer of 1954, Leonor fell head over heels for a special place in Corsica – a ruined monastery near Nonza. In this wild landscape, she felt in perfect harmony, and so returned every summer to paint.

A great lover of literature and poetry, Leonor illustrated more than 50 works by such writers as Charles Baudelaire, who she admired deeply, as well as Paul Verlaine, Gérard de Nerval, and Edgar Allen Poe. Among the writers and artists who dedicated monographs, essays, and poems to her were Paul Éluard, Giorgio de Chirico, Mario Praz, Max Ernst, Yves Bonnefoy, Constantin Jelenski, and Jean-Claude Dedieu. She continued as well to design sets and costumes for the theater, opera, and film: “Tannhauser,” at the Paris Opera (1963); “Le Concile d’Amour d’Oscar Panizza,” at the Théatre de Paris (1969); “Romeo and Juliet” directed by Renato Castellani (1953) and John Huston’s “A Walk with Love and Death” (1968).

In early 1960, Leonor Fini moved to an apartment in Paris’ rue de La Vrillière, between the Palais Royal and the Place des Victoires. Always in the company of her friends and her cats, she divided her time between the apartment and her home in Saint-Dyé-sur-Loire, in Touraine, up until her death on January 18, 1996.

A number of major exhibitions have been dedicated to Leonor Fini and her works: in Belgium (1965); in Italy (1983, 2005); in Japan (1972-1973, 1985-1986, 2005); in the United States (Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco, 2001-2002, 2006, 2008; CFM Gallery, New York, 1997, 1999); in Germany, at the Musée Panorama, Bad Frankenhausen (1997-1998); in France, at the Musée du Luxembourg (1986); at the Galerie Dionne (1997); and at the Galerie Minsky (1998, 1999-2009, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2007, 2008).

The city of Trieste mounted a large retrospective of her work, “Leonor Fini, l’Italienne de Paris,” at the Museo Revoltella (July-September 2009).

In 2008, the Musée d’Hospice Saint-Roch, in Issoudun, opened a permanent exhibition and installation replicating a room in the artist’s home, “Le Salon du Leonor Fini.”

The first biography dedicated to Leonor Fini and her work, “Leonor Fini: Métamorphose d’un art” by Peter Webb, was published by Imprimeries Nationale/Actes Sud, Paris, in 2007. Its English-language translation, “Sphinx: the Life and Art of Leonor Fini,” was published in 2009 by Vendome Press, New York.

http://www.leonor-fini.com/en/home/leonor-fini/biography.html

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Leonor Fini was born in Argentina to an Italian mother and an Argentine father of Italian descent. She and her mother fled to Italy after a tumultuous split between her parents. Fini spent much of her childhood dressing as a boy in public to avoid being kidnapped by her father—perhaps spurring a life-long interest in costume and masquerade.

Fini began her studies in Milan, but relocated to Paris in 1931 where she lived a flamboyant, bohemian lifestyle. She became closely acquainted with Surrealists André Breton, Giorgio de Chirico, and Max Ernst (a future love interest), and was included in many of their exhibitions. Yet Fini never declared herself a Surrealist because she refused to merely serve as Breton’s muse—viewing herself as an artist in her own right.

Inspired by the elaborate construction of gowns and the deception behind masks, Fini not only attended masquerades, but also worked as a costume and set designer. Costumes and performance also made their way into the artist’s paintings and drawings. In Two Dancers, the figures’ whimsical bodies are a combination of endo- and exoskeleton, juxtaposing life and death, the visible and the invisible.

- SBMA title card, 2013