Victoria Dubourg Fantin-Latour

French, 1840-1926

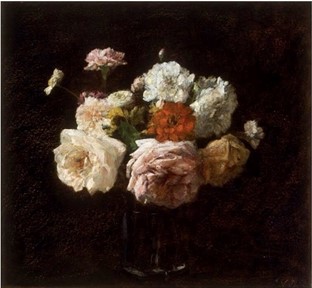

Roses, Zinnias, and Pinks, 1880 ca.

Oil on canvas

15 x 14 in.

SBMA, Gift of Dwight and Winifred Vedder

2006.54.5

Victoria Dubourg, by Edgar Degas, Courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art

“Victoria Dubourg should take her place in 19th-century art history primarily for the quality of her work.” -Elizabeth Kane

RESEARCH PAPER

Victoria Dubourg Fantin-Latour was a French still life and portrait painter. She was born in Paris to an educated and cultured family and trained privately under artist Fanny Chéron. In the 19th century, women were not admitted to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts until 1897. So many female artists, like Dubourg, studied, and practiced at the Louvre Museum, which acted as a forum for artists to network and socialize.

Dubourg received a permit in 1866 and financial compensation from the French government to copy several of the Louvre’s master paintings. She exhibited a floral still life at the Paris Salon in 1868, a year before she met her husband and collaborator, Henri Fantin-Latour, at the Louvre in 1869 while both were copying Correggio’s “The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria,” (1526-1527). By virtue of the Louvre, the couple socialized with leading Impressionist painters of their time, including Edouard Manet, Berthe Morisot, and Edgar Degas.

In addition, the Fantin-Latours were their era’s most leading and prolific artists working within the floral still life tradition. Most of their floral still lifes were sold to the bourgeoisie in Victorian England where the couple enjoyed more renown than in their native France. Perhaps because the Victorians communicated indirectly through the language of flowers or Floriography, thereby imbuing floral still lifes with greater meaning and purpose.

Moreover, Dubourg Fantin-Latour’s work is often overshadowed by her husband’s, due in part to the normalization and socialization of women in 19th century France, and her decision (whether coerced or not) to prioritize his work over her own. After they were married in 1876, they shared studio space at 8 Rue des Beaux-Arts in Paris and worked side by side, developing similar styles, but Dubourg signed her paintings with her birth name, perhaps to retain a distinct artistic identity. After Henri’s death in 1904, she spent nearly seven years of detailed scholarly work creating a catalogue raisonné of his oeuvre, which was published in 1911 and is still widely referenced today.

Dubourg Fantin-Latour worked in the traditional salon style of realist painters, who rejected academic art’s emphasis on idealized classicism and instead sought to paint the natural beauty inherent in common, ordinary objects from direct observation to elevate them to the realm of art. She was also influenced and inspired by the Master still life painters, Jean Baptiste Simeon Chardin (1699-1779), and Willem Kalf (1619-1693). Chardin favored simple, everyday objects, textured still lifes and was concerned with compositional unity. Kalf depicted lavish, exotic objects and foods, was concerned with realistic, detailed depictions, and employed chiaroscuro to emphasize patterns and textures. Dubourg Fantin-Latour’s work similarly emphasizes textures, dimensionality, and natural lighting.

In “Roses, Zinnias, and Pinks,” ca. 1880, Dubourg Fantin-Latour illustrates an elegant and sumptuous arrangement of a variety of fresh roses, zinnias, and other pink flowers in a widely fluted glass vase. She illuminates the bouquet from the left side of the canvas as it emerges from a dark textured background. The overall emphasis is on the mass of sensuous flowers, which holds center stage in the composition. The central bulls-eye placement of the red zinnia creates radial balance as the viewers’ eyes are masterfully pulled around the bouquet, first counterclockwise by the tallest flowers on the left, then around to the rightmost white flower, and back down to the same white colored highlights of the glass vase. Dubourg Fantin-Latour invites many visual rotations until the entire composition blooms before one’s eyes, unfolding many layers of loose, fluttering, and flurrying impasto brushstrokes. While simultaneously revealing a detailed eye and fastidious studies of botanical anatomies. One can almost breathe in the heady fragrance of the freshly cut flowers likely picked from the Fantin-Latours’ country estate garden in Buré, Orne in Lower Normandy.

Dubourg Fantin-Latour further produces visual harmony in her still life by the almost monochromatic coloring of her flowers (most flower colors are some value from the central red zinnia hue) contrasted with the green and yellow of their leaves. Moreover, the bouquet colors are soft and flowy and seem to blend and mix seamlessly with each other. Rhythm and dimensionality are composed by the repeated and varied bloom shapes, proportions, and colors, by the varied spaces in and between the flowers, and by her adept use of chiaroscuro. Moreover, she constructs textures by building up and subtly layering oil paints that visually read as patterns, which dynamically compliments, reinforces, and enhances the entire composition. Thus, Dubourg Fantin-Latour achieves overall unity of her composition through colors, shapes, chiaroscuro, and textures.

As Art Scholar, Elizabeth Kane rightly points out, “Victoria Dubourg should take her place in 19th-century art history primarily for the quality of her work,” (Kane, p. 15). Starting in 1869, Dubourg was invited to exhibit her still life paintings at the Paris Salon, and at the Salon of French Artists, where she was awarded an honorable mention in 1894 and a medal in 1895, respectively. She also exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. In 1920 she was named Chevalier of the Legion of Honor for her achievements as an artist.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Cyndi Withrow-Aliabadi, 2025.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/victoria-dubourg/

“Camille Claudel.” Directed by Bruno Nuytten, 1988.

https://www.famsf.org/stories/victoria-dubourg-and-the-louvre-the-museum-as-school-for-female-artists

Kane, Elizabeth. “Victoria Dubourg: The Other Fantin-Latour.” “Woman’s Art Journal,” vol. 9, no. 2, 1988, pp. 15–21. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1358315. Accessed 22 Jan. 2025.

“l’Oeuvre Complet [1849-1904] de Fantin-Latour. 1911.”

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/19wa/hd_19wa.htm

Roux, Jessica. “Floriography: An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers.” Kansas City, Missouri, Andrews Mcmeel Publishing, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iv64QzEhAX8