Lalla Essaydi

Moroccan, 1956- (active America )

Converging Territories #30, 2004

chromatic print, ed. 13/15

SBMA, Museum Purchase with funds provided by JGS, Inc.

"My work is very process-oriented. I believe the time I spend making the work is the defining aspect of being an artist. The process of making generates new perceptions and facilitates personal transformation, which in turn may yield new forms of expression. The arc of the entire process, from start to finish, is very liberating." - Lalla Essaydi

RESEARCH PAPER

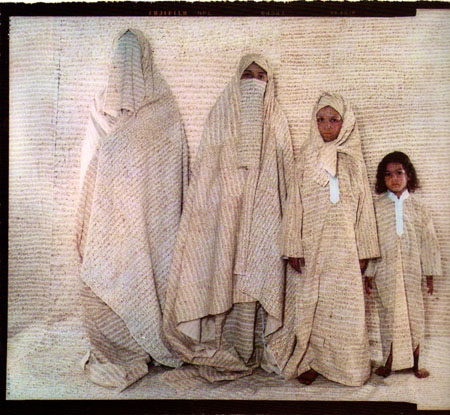

Finely-wrought lines of Arabic calligraphy scurry across the heavy drapery that covers nearly the entire image in Lalla Essaydi's photographs in her Converging Territories series. The piece owned by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art shows four women at different stages of life standing shoulder-to-shoulder in ascending height and age. Essaydi's writing, which originates in her diaries on her experiences of Moroccan Muslim femininity, wraps the women and delineates the shallow, stage-like space from which they gaze back at their viewer.

As a Moroccan-born artist living and working mainly in the West, Lalla Essaydi's photography challenges the artistic and visual dialogues inherent in colonialism. In this sense, Essaydi very much describes herself as a cultural mediator who invites viewers to reconsider stereotypes. Orientalism emerges as perhaps the most important concept to which Essaydi's work may introduce its viewers. In her first major series, Les Femmes du Maroc (The Women of Morocco), Essaydi quotes the paintings of European masters who created an imagery of Eastern luxury and exoticism. The photos in this series feature women in the same poses as women in these canonical works, such as Ingre's La Grande Odalisque , and show the beginnings of Essaydi's distinctive visual vocabulary. Text coats her subjects in those photos as well, yet in Converging Territories , Essaydi pushes the concept of writing further.

Converging Territories indicates Essaydi's history as both a painter and a photographer, and our photo began as a painting of sorts. The first step in creating these works is a process undertaken over a period of months, when Essaydi inscribes bolts of fabric with her own writing. This writing is painted with henna, a material associated in Islamic cultures with women's crafts. Yet writing is a traditionally masculine pursuit, which in Islam is a sacred art that was long inaccessible to women. The text in the photograph intrigues the viewer with a poetic and delicately textured scene. Underlying its visual appeal, though, is a challenge: In Essaydi's materials and subject matter, antagonisms converge. Our photography comments on tensions between male and female, public and private, silence and subversion.

Henna is a dye derived from a flowering plant that can be used to temporarily tattoo the skin. It is applied during major celebrations and especially to mark the passage of a girl into puberty. The application is painstaking, and cannot be interrupted once it is started. Thus, in applying the henna seen in these photos, Essaydi and her models (friends and family) were unable to rest for up to nine hours. In these photo shoots, the artist provided music, food and drink to her collaborators, with whom she told stories and demonstrated the complexity of their Arabic artistic heritage. The performative dimension of this work is crucial, both for the agency implied in authoring identity and for the direct reference to an audience.

Once all the fabric has been inscribed, continuous cloths join the women and their setting. Through the use of this tan and white calligraphic pattern and others, Essaydi often drapes her subjects in the same pattern as that which she places in their background, forcing a visual flattening. The figures retreat, making their undeniable presence all the more stunning. Her use of pattern to manipulate depth and the relationship between subject and setting creates visual unity in the piece. Yet just as it partially obscures the forms of her subjects, it also confounds their environs.

Space is an immensely important conceptual aspect of this photograph. The photos in the Converging Territories series were all taken in an uninhabited house owned by Essaydi's family in Morocco. Following a punitive standard in Moroccan culture, this home was used during Essaydi's childhood for secluding members of the family who transgressed spatial gender rules. Across the Arab world, it is traditional for men to occupy the public sphere and for women to remain indoors at most times. Interiors of homes also have complex spatial rules relating to gender, and disobeying them led in Morocco to women being required to spend periods as long as a month in otherwise uninhabited homes. The set for Essaydi's photograph, then, is the very house in which she was held when punished during her youth. By exposing its interiors and a narrative of womanhood that emerges from it, Essaydi's oeuvre is quietly subversive, showing places where women are seen rather than hidden.

Essaydi's work is full of complex contradiction, however. According to a formidable tradition of Orientalism, still being generated and internalized by subjects in and beyond the West, visualization is a vital part of colonization. Subjection to the Western gaze, which in Essaydi's photo could be seen as liberating, is perhaps not so different from the type of engagement viewers have traditionally had with Orientalist works of art. Essaydi's work has been criticized along these lines, under the impression that her appropriation of an Orientalist dynamic leaves it too unchanged. Yet this double entendre is central to the efficacy of her setting. If Orientalism is a system of thought premised upon exteriority - moral and existential - whose main product is representation, then photographs of the private interior allow Essaydi to cut straight to the heart of what Edward Said called a process of "intimate estrangement."

The frontality of the figures in this work, the monochromatic scheme, the gossamer textuality, and the illegible space the figures inhabit coalesce into a careful consideration of the contradictions of postcolonial Muslim femininity, at least as articulated by Essaydi. This lofty goal is a potential point of criticism, for the artist somewhat glosses over the differences internal to what she calls "sisterhood." Nonetheless, our photograph is characteristic of the visual style and political concerns of Lalla Essaydi, whose work is owned by collections all over the world.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art by Stephanie Amon on April 5, 2012.

Suggested Resources:

Carlson, Amanda. "Leaving One's Mark: The Photographs of Lalla Essaydi." Converging Territories . New York: PowerHouse, 2005. Print.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism . New York: Pantheon, 1978. Print.

"Women and the Muslim World - Patrons, Artists, Muses, and Instigators," panel discussion on the Galleries of the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. February 14, 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bjWCco-EUGU