Louis M. Eilshemius

American, 1864-1941

Plaza Theatre, 1915

oil on composition board

30 1/2 x 40 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ira Gershwin

1956.5.2

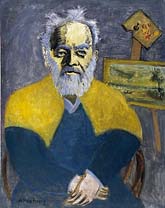

Portrait of Louis M. Eilshemius, Oct 4, 1913, photograph by Jim None Saah

DARKNESS IN THE ROOM

When the evening shadows fall

On field and wood and plain

and darkness settles in my room—

I play—and to song’s Spirits call:

Then follow strain and strain

of music, all with dreams abloom!

‘Tis a magic melody flows:

Oh! such Beethoven could

Evolve from his wild heart and soul

The Seraph of music only knows

To fill my solitude

With songs whom Heaven’s hosts control!

Then come to me when darkness palls,

The room and all is still—

From forth my fingers rare tunes come fast

No mortal’s melody recalls

But all your feelings fill

With heaven’s dream and bring sweet joy to last.

LOUIS M. EILSHEMIUS, M.A.

October 24, 1931

RESEARCH PAPER

Louis Eilshemius’ early paintings were almost entirely devoted to landscape, with nineteenth century attention to detail and spatial depth. His style underwent a radical transformation about 1910. A change can be noted from his earlier lyrical style to a more somber mood as depicted in Plaza Theater. He has taken liberties with drawing and scale. The palette has darkened, showing his fondness for browns and greens, which dominate the foreground. The actors on stage—three male figures, one in blackface—are crudely portrayed. His interest at this time focused on genre subjects. One can speculate that what we have in this work is Eilshemius’ poetic and sympathetic response to urban life.

These theater subjects became common after 1910, precisely at the time when Eilshemius’ work began to undergo its most dramatic stylistic change. Paul Karlstrom (Eilshemius, 1978) states, “A special ‘stage’ style, based on the artifice and unreality inherent in the subject, could very well have contributed to the evolution of the artist’s work.” Connoisseurs of the naïve admired the artless way in which Eilshemius put together his Plaza Theater.

As an economy measure, Eilshemius was no longer filling out the conventional rectangle of the picture space; he was enclosing it within an irregularly curved border. He contrived these “selfmade frames,” yellow borders painted onto masonite, continuing their use until he gave up painting altogether.

Louis Eilshemius was the product of the Victorian era. He was born in 1864 in New Jersey to a wealthy and privileged family. He had the advantages of a foreign education and a stimulating home environment. His father provided him with financial support for extensive travel and study. The declining curve of his professional and personal life is in dramatic contrast to his propitious beginnings.

His life is one of intrigue, full of pathos, frustration, deterioration and ultimately poverty and tragedy. During Eilshemius’ early years, his landscapes reflected joy and spontaneity. His frame of reference may be broadly defined in terms of the native Hudson River realist tradition, qualified and transformed by contemporary French landscape painting. He was influenced by George Inness and Camille Corot.

Eilshemius was an extreme individualist. This trait increasingly asserted itself over the years, ultimately producing an expression unique to the artist. His painting was frequently naïve or eccentric and highly personal, often expressing his inability to attain emotional maturity in his personal life. Many said of him that he painted like a ‘primitive,’ but of course, he was not. He was a thoroughly and well-trained artist who prided himself not only on his versatility and wide range of subjects but also on his rapidity of execution. However, he attempted too many art forms, thereby dispersing his energies.

The crucial break in his career seems to have come about 1910. His growing sense of isolation and discouragement eventually affected both his work and personal behavior. He began the practice of visiting galleries and vociferously criticizing exhibited work. He started writing letters to newspapers and art periodicals. He printed and distributed self-praising handbills. He began using the title “M.A.” after his name although he had not earned the degree. He adopted the pseudonym Mahatma and described himself as the “all supreme genius, world’s mightiest mind, and the Scientist Supreme.” All of his efforts brought personal notoriety but not recognition of his art.

The sources and influences on his later career are difficult to pinpoint. Eilshemius did not join any school or group of painters. It is in his theater interiors that he comes closest to the Ashcan school. Stylistically, he is nearest to John Sloan and even Robert Henri. However, there is a degree and quality of romanticism that separates Eilshemius’ work from that of the Eight. His sensitivity to the rich human drama surrounding him is evident in his depictions of the vaudeville stage.

As with Post-Impressionism and early twentieth century Modernism, Eilshemius’ work utilizes a shallow space, simplification of form and flat pattern design. He was influenced by Art Nouveau, bur perhaps the change was due more to internal factors rather than external influences.

About 1917, Eilshemius received recognition by Duchamp, who devoted a great deal of energy and expense to his exposure. He was also praised by other progressive artists, among them Gaston Lachaise, Joseph Stella, Charles Demuth and Abraham Walkoitz. However, the hostility from critics and the public was more than Eilshemius could endure. In 1921, he abandoned painting forever.

There was a revival of interest in his work in the 1930’s. Critics were eventually won over, but it came too late for Eilshemius to derive any pleasure from the recognition. After an auto accident in 1932, he was paralyzed and confined to his room. During his last years, his money was gone, he was without friends, and his mind was completely divorced from reality. In December of 1941, he was taken to Bellevue Hospital in New York where he died of pneumonia.

PROVENANCE

The early history of Plaza Theater is unknown. It may have been sold by Valentine Dudensing, a dealer for Eilshemius, through his Paris gallery to Ira or George Gershwin. It was in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Ira Gershwin by 1939 and gifted from them to the SBMA in 1956.

Bibliography

Bernard Danenberg Galleries, New York, “The Romanticism of Eilshemius,” April 3-28, 1973.

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, “Louis M. Eilshemius, Selections from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden,” 1978.

Karlstrom, Paul J. Louis Michel Eilshemius. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1978.

Larking, Oliver W., Art and Life in America. New York: Rinehart and Company, Inc., 1949.

Miller, Arthur, “Los Angeles,” Art Digest, Vol. 26, No. 12, March 15, 1952, pg. 15.

Schack, William. And He Sat Among the Ashes, A bibliography of Louis M. Eilshemius. New York: American Artists Group, Inc., 1939.

Prepared for the Docent Council of SBMA by Nell Welling, March, 1985.

Prepared for the Docent Council website by Molora Vadnais, edited by Lori Mohr, Fall 2012.

Self-portrait of Louis M. Eilshemius, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Idiosyncratic painter who called himself a "Transcendental Eagle of the Arts" but whose increasingly subjective pictures received little attention during his lifetime. Charles Sullivan, ed American Beauties: Women in Art and Literature (New York: Henry N. Abrams, Inc., in association with National Museum of American Art, 1993)

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Simultaneously marginalized and championed for his eccentric behavior and subject matter, Eilshemius traversed a path similar to other better known artists—he trained at the Art Students League and in Paris, showed his work at the National Academy of Design, and had a studio at the famed Holbein Studios on West Fifty-fifth Street—but operated in a creative universe all his own. Painted during a period of intense productivity characterized by rapid execution and loose handling, Plaza Theatre features the imaginative elements of fantasy and unreality for which the artist is now best known. The composition utilizes the stage space, painted scenery, and artificiality of the theater to express the dislocations of modern life and demonstrates why avant-garde artist Marcel Duchamp and Katherine S. Dreier of the progressive Société Anonyme selected him for its first one-man show.

- SBMA Gallery Label, 2012