John Divola

American, 1949-

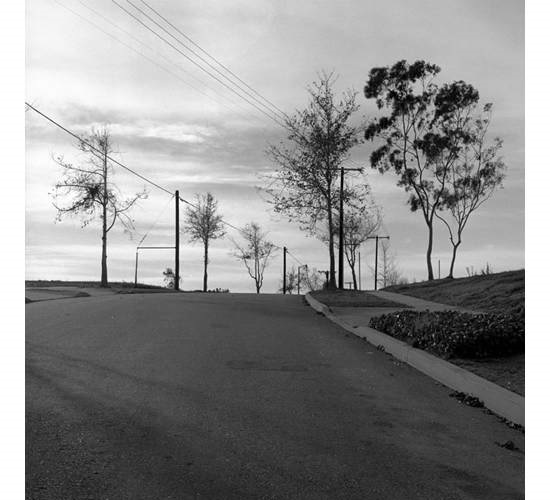

LAX/Noise Abatement Zone Series, 1976-1978

Gelatin silver print, printed 1982

20 x 16"

Courtesy of the Artist

“I was really interested very early on in the forced entries…not from a social point of view but from a physical, sculptural point of view. I was interested in someone physically breaking through and seeing the imprint of this action…It’s an action that interests me, that I want to study.” - John Divola

COMMENTS

John Divola occupies a unique place in the art of the last few decades. The series collected here were made in the 1970s, a period of redefinition for art and photography. It was here that the very terms of visual art were transformed. At the center of the change was a widespread shift in art from what we might call the pictorial, or picture making, towards the performative or event making. At an extreme some artists gave up making traditional objects altogether to perform instead with their bodies. Others turned towards using photography because it seemed not to be an object at all, certainly not an object with the heavy baggage of painting or sculpture. But in the main it meant artists leaning towards ways of working that emphasized process. Art took the form of outcomes resulting from open-ended experimentation, improvisation and hypothesis. It assumed the look of collected data – marks, remnants, results, traces.

Being the pre-eminent medium for documents, photography was pivotal to all this but its role was fraught with contradiction. On one level all art was reliant upon photography to reproduce and publicize it. This was especially the case for the new art forms that broke out to explore the possibilities of installation art, Land art and performance art. Work could be made anywhere, anytime, in any form. Audiences could come to know it via images appearing in magazines, journals and catalogues. Art was free to move into an ‘expanded field’ with an expanded art press to follow it. Yet, at the very same time the idea of the photograph as a neutral transmitter was being teased apart. Artists were fabricating things to be photographed; undermining the image with contradictory captions; or seeing the photograph as no more automatically realist than words or paintings.

Divola took his own intuitive line through the tangle. In producing these series he was certainly involved in doing things and making things in places outside the gallery, which he then photographed. In this sense he folded into photography key aspects of installation, Land and performance art. But where those forms relied on the supposed transparency of the photograph, Divola also went about a comprehensive inquiry into its nature and conventions. There was no better mode in which to test the limits of the document than the forensic photograph. This after all is a type of image backed by the full institutional force of the state. It is invested with unparalleled authority and seen as proof. The archetypal forensic image is a photograph of a floor or ground taken from eye level. A downward tilt of vision turns incidental details on a receding plane into signs for our attention. The lowered angle also emphasizes the body of the photographer or viewer as a present witness. It places us at a threshold between the closure of an event that has taken place and the opening of its investigation. Divola made a number photographs that take this form. At times his camera stares down at surfaces covered in mixtures of scattered debris and arranged patterns. Of all his photographs these are the ones that could be said to have something in common with the work of others made around the same time. Indeed, looking back it is surprising just how often this visual trope recurred across the art of the late 1960s and 1970s. We see it for example in Bruce Nauman’s documentation of temporary sculptural forms such as Flour Arrangements (1966). It is in Edward Ruscha’s Royal Road Test (1971), his parodic investigation of the wreck of a typewriter hurled from his moving car. Lewis Baltz made use of it in his series of cool topographic photos of suburban building sites such as Nevada (1977). It opens Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s Evidence (1977), their book of puzzling photos gathered from scientific archives. Ana Mendieta’s Silhueta series (1978) of her own bodily outline have this gaze as do Mac Adams’ Mysteries of the late 1970s and 80s, his enigmatic photo stories set in motion by apparently incidental traces. This was a period of art that is thought to have had no unifying style. The widespread anti-formalism of the time almost went out of its way to refute style. So the prevalence of this sort of ‘paraforensic’ image all the more telling. Its look is so artless that it lends itself to all kinds of art interested in the idea of the trace.

In typical forensics the ‘event’ has already happened and the photograph comes after it. The photographer arrives at the scene late, so to speak. Divola’s series ‘Los Angeles International Airport Noise Abatement Zone’ (‘LAX NAZ’) just about obeys this rule. The zone in question was a swathe of houses bought by the airport to meet noise pollution targets. Decommissioned as homes they stood empty. Divola began to photograph them and to document the evidence of the inevitable break-ins. His photography is cool, formal and conventional. By contrast in the Vandalism and Zuma series many of the actions recorded are of Divola’s own making. He commits what for forensics is the cardinal sin. Where the police photographer responds dispassionately to what is there, recording without touching, Divola acts as mark maker, arranger and orchestrator as well as recorder. He responds as a photographer to his own actions as a painter, sculptor and installer.

Making art out of ruins has been a part of culture at least since the Dadaists worked the flotsam of modern life into their collages. And photographing ruins is as old as the medium itself. Cameras seem drawn to them. Divola’s engagement with detritus is altogether more complicated. To begin with he erases the boundary between making and breaking. His interventions in vacant spaces complement and extend what we know and expect of vandalism. He works with the vandal’s tools and his simple language (if we can call it a language), refining what constitutes the sprayed mark, the daub, the tear and the cut. But they are not turned wholly into something else. Mindless or repetitive destruction gives way to artful fabrication but slips back again. Objects and surfaces appear to move between intention and carelessness. The photographs show us the results of enactments that swing from destructive creativity to creative destruction, revealing and then reveling in the hidden craft of ruination. They turn damage into an object of aesthetic contemplation without ever letting us forget its destructive character in the social world.

Divola works in half abandoned spaces with the intense play and experimentation we associate with the studio based artist. But his is no private realm. We are reminded that the buildings are not his private domain. His presence and his means are fugitive, just as the spaces themselves are in transition from one social use to another. His images are records of past events, documents of things done before the photograph was taken. However each one is also an event in itself. This comes across in different ways. Firstly there is the use of series. Each image is a pause in an unfolding, improvised situation. It comes after what has been done but before what is to come. The space we see may be changed into something else. The image is not a final report but provisional marker. Secondly Divola frequently welcomes the way the camera image transforms three-dimensional space into graphic flatness. The classical forensic image is careful not to draw too much attention to itself. Divola shoots in ways that allow his marks to belong both to the real space and to the flatness of the photograph. The grids, dots and curves can often appear to hover between the space depicted and the surface of the image. The effect is often estranging, leaving photography itself hovering, somewhere between fact and fiction. We are lured by the promise of forensic objectivity but reminded that photography is always a transformative act. Lastly the photographs may become events through another kind of hovering. Some of Divola’s strangest shots include found magazines or bits of fabric hurled into the air and caught by electronic flash. Forensic photography emphasizes the camera’s lens through which passes the stilled world. It tells us the event is over and can be gazed upon at a remove. But nothing signals an event like an instantaneous exposure or a flash strobe that freezes movement. Here the burst of light and the shutter are emphasized along with the lens. The coolness of a lens gives us a slice of space, a shutter or flash cuts a slice of time. Divola’s rarely settles for one or the other. He is not interested in anything clear cut.

David Campany, " Who, What, Where, With What, Why, How and When? The Forensic Rituals of John Divola," Flickr Photos, 28 May, 2010

http://varrone.wordpress.com/2010/05/28/ba-zuma-from-zuma-series-by-john-divola-1975/

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

The LAX/NAZ Abatement zone was once comprised of thriving neighborhoods surrounding the Los Angeles Airport, but the need to expand the airport as well as to mitigate the noise prompted the city to buy entire blocks of homes. Abandoned and empty, until either bulldozed or moved, the houses became irresistible targets for unknown actors who happened upon the scene.

From his earliest series to his most recent projects, Divola has returned to buildings that at some point served as human habitation. From the outside looking in and vice versa, the photographer has documented abandoned, forlorn structures whose interiors were bared to the elements and to random vandals, vagrants and the occasional artist, but the viewer has no idea who or what social forces have acted to bring about change.

John Divola’s photographs are authentic recordings of what is, but one will never know the how or who behind the evidence. His visual explorations in these spaces offer indisputable proof of his presence, or as the artist likes to note, are an “authentic imprint of circumstance,” though not of the actions that created the scene. His photographs have a quality of impermanence, while at the same time, asserting authenticity.

- John Divola, As Far As I Could Get, 2013