Michael Disfarmer

American, 1884-1959

Untitled (elderly seated man in pin striped suit with seated woman in dark dress, striped background), 1930-1952 ca.

gelatin silver print

3 × 4 5/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Michael Yanover and Rhonda Milrad in memory of Philip Yanover

2016.32.6

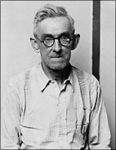

Undated Self-Portrait

"...haunting, uncompromising view of middle America caught in the tumult of World War II." "...Disfarmer's portraits reveal an essential human quality reminiscent of Diane Arbus studies." - Los Angeles Times, 1977

COMMENTS

The eccentric photographer known as Disfarmer (1884-1959) seemed to be a man determined to shroud himself in mystery. Born Mike Meyers, the sixth of seven children in a German immigrant family, Disfarmer rejected the Arkansas farming world and the family in which he was raised. He even claimed at one point in his life that a tornado had lifted him up from places unknown and deposited him into the Meyers family.

In time Mike expressed his discontent with his family and farming by changing his name to Disfarmer. In modern German "meier" means dairy farmer, and since he thought of himself as neither a "Meyer" nor a "farmer," Mike Meyer became "dis"- farmer.

Perhaps, it was his desire to break free of his Arkansas roots that led him to photography. He taught himself how to shoot and develop photographs, and he soon set up a studio on the back porch of his mother's house in Heber Springs, Arkansas.

In the 1930s a tornado swept through the Heber Springs valley destroying the Meyer home and forcing his mother to move in with a relative. Shortly thereafter, Disfarmer built a studio on Main Street and became a full-time photographer. Using commercially available glass plates, Disfarmer photographed his subjects in direct north light creating a unique and compelling intimacy. He was so obsessed with obtaining the correct lighting that his lighting adjustments for a sitting were said to take sometimes more than an hour.

Disfarmer's reclusive personality and his belief in his own unique superiority as a photographer and as a human being made him somewhat of an oddity to others. Having your picture taken at Disfarmer's studio became one of the main attractions of a trip into town.

After Disfarmer's death in 1959, retired Army engineer Joe Albright bought the Disfarmer studio, including its contents, from estate executors. As he and his sons picked through the abandoned studio, they found thousands of dollars hidden away in film plate boxes. The true bonanza, however, was the discovery of more than 3,000 glass plate negatives. Having an interest in photography, Albright carefully stored the negatives in his basement hoping one day to "do something with them."

In 1974, professional photographer Peter Miller and his wife moved to Heber Springs to publish a weekly newspaper, The Arkansas Sun. When The Sun ran a new main page feature, "Some Day My Prints Will Come," featuring old family photographs submitted by readers, Albright submitted some of Disfarmer's work.

Recognizing the unique artistry of the Disfarmer photographs, Miller purchased the collection of negatives from Albright, published the portraits for a year in The Sun, and forwarded copies to Julia Scully, editor of 'Modern Photography' magazine. From her initial viewing of the photographs, Scully recognized the unique qualities of the photographs and since then has worked to bring Disfarmer's portraits into public view.

Scully worked with Miller and the Addison House to publish the first book of Disfarmer's work, Disfarmer, the Heber Springs Portraits 1939-1946. Reviewers embraced the work as "... one of the most significant bodies of work in the history of portraiture."

Disfarmer's unique portraits are included in the permanent collections of the New York Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Arkansas Arts Center Museum and the International Center of Photography in New York City. Disfarmer's work has also been exhibited in museums and galleries throughout Europe and the United States.

Nothing speaks more eloquently about Disfarmer's artistry than the photographs themselves. His genius was the ability to capture without judgment, the essence of a people and a time.

http://www.disfarmer.com/

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Michael Disfarmer was an idiosyncratic photographer whose work remained unknown to the larger world until the later 1970s. Living in Heber Springs, Arkansas from the 1930s to the 1950s, Disfarmer served the town and surrounding areas during two important eras in U.S. history: the Great Depression and the Second World War. Disfarmer’s studio was sold after his death; his glass plate negatives remained on his property until the mid-1970s when they were rediscovered by a local newspaper. Since then his works have gained renown for their remarkably direct and revealing picture of a small Arkansas farming community and a time in United States history that have long since disappeared.

Disfarmer was born Michael Meyers. He renamed himself Disfarmer to disassociate himself from his family’s farmer origins, and considered himself a business owner rather than a high art photographer. His portraits however transcend the commercial by an unmistakable modern clarity that allows sitters to reveal themselves more directly than traditional studio poses permitted. Disfarmer’s methods were simple: he placed his subjects sitting or standing in a neutral setting, often before a wall with a single vertical stripe. He then photographed them from a distance that allowed enough space around his subjects so that viewers instinctually perceive these people as immediately real, rather than distant characters in an elaborately fake tableau.

In this way Disfarmer’s work can be compared to that of the early 20th-century German photographer August Sander, the postwar American photographer Diane Arbus, and contemporary Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra, all of whose work deals with public and private personae as captured by the exacting lens of the camera. These intriguing works, acquired by recent gift, are the first Disfarmer photographs to enter the Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s collection and are on view at the Museum for the first time.

- Crosscurrents, 2018