Lewis deSoto

American, 1954-

Paranirvana (Self-Portrait), 1999-2015

painted vinyl infused cloth (polyethylene), electric air fan, 4th in a series with variations

approximately 26 ft, dimensions variable

SBMA, Commission

POSTSCRIPT

In Buddhism, parinirvana (Sanskrit; Pali: Parinibbana) is the final nirvana, traditionally understood to be within reach only upon the death of someone who attained complete enlightenment. It is the ultimate goal of Buddhist practice and implies a release from the cycle of deaths and rebirths as well as the dissolution of all mental aggregates (form, feeling, perception, mental fabrications and consciousness).

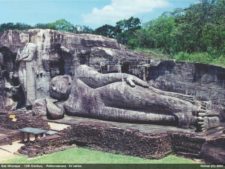

Prof. Chandra Wikramgamage of Sri Lanka writes: Only a few countries in the world can be proud of long lived traditions of art and architecture. Of the few countries, which possess such traditions of art, and architecture, which could be considered as a world heritage, Sri Lanka is one. Here, there exists a multitude of incomparable creations of art and architecture, which have evolved throughout a lengthy period of 2500 years. The Gal Vihara, which belongs to the middle ages, is such a creation. This creation, which is unique in all three aspects, architecture, painting and sculpture, has achieved a greater excellence in sculpture. There is no doubt that the massive images of the Buddha, that have been completed with a combination of proportion, external beauty, Mudra and life through facial expressions, specially the sedent image in the left corner and the standing image that is to the right of the recumbent image, have kept the observers spell-bound for about 800 years from the 12th century, when they were created, up to the present day. No other place in the world can be found, where one observing the images at dawn or in the evening can experience the love for humanity, peace and happiness that is depicted by them. The greater the number of times one looks at them, each time one sees something new in them that deepens one experience. The craftsman or the craftsmen possessed the capability of leading the observer towards spiritual happiness. Cultural tourists, art historians and those seeking spiritual peace, repeatedly visit Gal Vihara discarding national and religious differences, because of its incomparable beauty. Unquote Prof. Chandra Wikramgamage of Sri Lanka. The paragraph is quoted by courtesy of the good professor.

Location of Gal Vihara

The Buddha statues at Tantrimalai close to glorious capital of ancient Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) though almost as massive as the Buddha statues at Gal Vihara once called Uttararama (Sinhala: The Northern monastery), in view of being located in the northern sector of the sacred city of Polonnaruwa (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) is about 18 km north of the promontory situated between Parakrama Samudra, and the Citadel at the early medieval city of Polonnaruwa. It is less than half a kilometer from the extensive oblong site, artificially banked up, whereon are located Kiri Vehera Dagaba, Jetavana Dagoba and other historical, cultural and archeological attractions.

Four caves at Gal Vihara

Gal Vihara consists of four cave shrines having statues in the three postures in four cave shrines named Cave of Vijjadhara, Excavated Cave, Cave of Standing Image and Cave of Reclining Image. The sockets cut into the rock behind the statues testify that the walls had originally separated each four statue from one another. So do the ruins of the foundations of the brick walls separating the four caves.

The Cave of Reclining Image

The space between the eyes measured one foot, the length of the nose 2 ft. 4 in., and the little finger of the hand under his head 2 feet. Now, you can guess the size of the figure: 46 feet (14 meters). In spite of the colossal proportions, the delicateness of the features are of supreme serenity and sublimity.

The pillow is black rock granite yet the unknown sculptor has carved the statue of heroic proportions with such tenderness even the bolster like pillow has taken a slight depression under the head.

The Reclining Image: posture of parinirvana final extinction or posture of reclining

Buddha's parinirvana (final extinction, rather than death, following the life in supreme enlightenment, braking free of the cycle of death and rebirth) seems to be indicated in part, by means of the higher foot which is slightly withdrawn: the pain caused by the last breath. Is it? Perhaps not. This posture coupled with the placing of the head resting of the right palm is called Simhaseyya (Sinhala: Lion-posture): the lion sleeps resting its head on their right paw.

Moreover, the final extinction (passing away beyond death) is depicted in Buddhist art with the accompanying images of disciple, sal trees and flowers dropped by god (resplendent and superior being in other worlds). Such features exist in Gandhara art and in Ajanta in India.

Here is the mystic, Thomas Merton, on Polonnaruwa and the Gal-Vihare six days before his accidental death in Bangkok. "Polonnaruwa was such an experience that I could not write hastily of it..its vast area under trees. Fences. Few people. A dirt road. Lost, we find Gal Vihara...The path dips down to a wide, quiet hollow surrounded with trees. A low outcrop of rock, with a cave cut into it, and beside the cave a big seated Buddha on the left, a reclining Buddha on the right, an Ananada, I guess, standing by the head of Buddha. In the cave another seated Buddha... I am able to approach the Buddhas barefoot and undisturbed, my feet in wet grass, wet sand. Then the silence of the extraordinary face. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing everything, rejecting nothing..without refutation, without some other argument...I was knocked over with relief and thankfulness at the obvious clarity of the figures...Looking at these figures I was almost forcibly jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious... there is no puzzle, no problem, and really no 'mystery'... All problems are resolved and everything is clear...Surely...my Asian pilgrimage has come clear and purified itself... I know and have seen what I was obviously looking for. I don't know what else remains but I have now got beyond the shadow and the disguise...' Whatever one feels about the meaning and message of this early Buddhist work, its grandeur cannot be denied.

Buddhist monastic architecture in Sri Lanka; the woodland shrines

Anuradha Seneviratna, Benjamin Polk 1992 Abhinav Publications 1992 Architecture

COMMENTS

Art That Breathes: Lewis deSoto’s Paranirvana (self-portrait)

Edited from Research by © Anya Montiel, Yale Education

Lewis deSoto’s Paranirvana (self-portrait) is a 26-foot long sculpture influenced by the artist’s engagement with Buddhism. The sculpture depicts a figure reclining on its right side; its disposition closely based on a twelfth-century stone Buddha at Gal Vihara in Sri Lanka. Unlike its solid stone predecessor, deSoto’s work, made from painted polyethylene cloth, is hollow, filled only by air from a fan that keeps the sculpture inflated. The resemblance to the reclining Buddha is nonetheless remarkable, from the curls of hair to the folds of the robe, the one exception being that deSoto superimposed his own facial features, complete with goatee, on this Buddha. These alterations to material and the personalization of the piece that occurs when it becomes a self-portrait, make particular claims on this representation and shape its possible meanings.

deSoto was born in San Bernardino, California in 1954 to a Latina mother and a Cahuilla (Native American) father. Raised a Roman Catholic, the artist has been a student of Buddhism for more than thirty years. Initially he studied philosophy at University of California, Riverside where a professor who was formerly a Jesuit priest encouraged him to learn more about Buddhism and Hinduism. deSoto decided to minor in religious studies as a complement to his studio art major. He also did coursework with Buddhist scholars Francis H. Cook at Riverside and Masao Abe at the Claremont Graduate School where he completed his MFA in 1981. He has been a professor of art at San Francisco State University since 1988. His body of work ranges across many media. He has often created culturally-specific and site-specific installations, transforming spaces through light, audio, and video technologies. As a conceptual artist, he generally works with immediately recognizable objects, altering their meaning in exhibition settings.

In 1998, deSoto’s father, a man the artist considered indestructible, passed away. At the wake for his father, deSoto approached the open casket and touched his father’s chest, noting with some wonder that it felt cold and hollow like a drum. deSoto relates that he sensed then that the body was only a shell, and his father was not there. His father’s death, furthermore, invited him to contemplate his own mortality. deSoto asked himself, “what happens when you die? What is that experience like?”1

deSoto recalled the event of parinirvana or the “great liberation” where Buddha entered an enlightened “state of ultimate spiritual transcendence,” released from the cycle of death and rebirth.2 The historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, while he lay dying from food poisoning, gave lessons about consciousness and samsara (the cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth). deSoto looked at the Gal Vihara Buddha, which depicts the parinirvana, and thought about recreating a similar self-portrait that would be large in size but light in weight. deSoto superimposed his face on a photographic image of the reclining Buddha, and a San Diego company produced an identical custom inflatable sculpture with airbrushed detailing. In idealizing his version of parinirvana, deSoto entitled it Paranirvana to express a “large liberation.”3

From afar, deSoto’s inflatable Buddha gives a trompe l’oeil effect with its tan hue mimicking stone.4 Upon closer observation, creases in the seams of the cloth are evident. Also, the sculpture makes noise—a hum emanates from the fan inflating it. deSoto purposely added sound, giving it breath.5 In Buddhism, a mindful breath is an essential part of practice. Buddha taught, “Breathing in, I see the earth element in me. Breathing out, I smile to the earth element in me.”6 Breath is a sign of life and connects living beings to the lived universe.

Although hidden from view, the fan is an important component of Paranirvana. Symbolically, it provides life—and death—to the sculpture. The sculpture arrives at a venue rolled in a small crate. As the sculpture lies flat on the floor, the fan rouses movement and brings it shape, slowly filling every cubic inch with air. When fully inflated, Paranirvana rises to a height of six feet and spreads to occupy twenty-six feet in length. Once the fan is unplugged, the air seeps through an opening in the back. deSoto describes that moment as “its last…breath.”7 Its end is peaceful; the head falls deeper into the pillow and the body gradually flattens. The sculpture reaches full deflation in thirty minutes with every part sinking into the ground.

Another Buddhist-focused exhibition, “The Invisible Thread: The Buddhist Spirit in Contemporary Art” at the Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art in Staten Island, NY, featured Paranirvana. Novelist and critic Joseph McElroy brought an “outsider's long-time interest [in Buddhism]” to his experience of the show.13 He reported being immediately struck by the size of the 26-foot inflatable Buddha. The whirling fan, he said, reminded him to breathe as the sculpture was breathing.14 Also McElroy understood deSoto’s use of self-portraiture as the artist’s aspiration to his own “future moment of Buddhahood.”15 Zen monk Shunyru Suzuki, who popularized Buddhism in America and opened the first Buddhist monastery outside Asia, explained that, “everyone has Buddha nature” and that “the student himself is Buddha.”16 deSoto further clarifies that, “Buddha is not an idol…Buddha is not a god. Buddha is a person. He is an enlightened person.”17 By placing his face on Buddha, deSoto is visualizing his own Buddha nature.

Paranirvana commemorates, even embodies, a somatic event.18 The death of deSoto’s father triggered “a feeling of shock and grief…[loss] has such a physical manifestation.”19 His father’s death prompted him to contemplate his own ideal death and to create an immense living and dying self-portrait. Drawing on his studies of Buddhism, Paranirvana encapsulated the Buddhist tenets of samsara and reaching enlightenment. Its body is a shell, but it is full of breath. As its title conveys, Paranirvana takes one last breath to reach “the great liberation” then slowly deflates into a peaceful material death.

© Anya Montiel

HomeConversationsEssay

http://mavcor.yale.edu/conversations/essays/art-breathes-lewis-desoto-s-paranirvana-self-portrait

Lieutenant Mitchell Henry Fagan of the 2nd Ceylon Regiment, forcing his way through almost impenetrable undergrowth in the year 1820, encountered-face to face-a colossal statue gazing out at him from the foliage: Gal vihara. A colossal figure of Buddha cut from a granite wall was most serenely gazing at him from out of the foliage. "I cannot describe what I felt at that moment," he wrote.

..."Neither could I when I first saw the great statues. It was like dream that you dream when just about to wake up. And you wake up with the dream & still on a cloud. But the upright Big Buddha most definitely smiled at me. Am I dreaming? No, Big Buddha smiled again." That's bunpeiris. There sprang up an eternal love on the spur of the moment: Gal Vihara was no longer a rock temple of rock carved statues. It is the heartthrob. If it was the flow of the sculptor's heart then, since then, it has been the stream that wash and cleanse the minds and the hearts of all those who stand in front of it. Stand, kneel or sit in front of the great statues. The sweeping serenity of the statues would breeze-open your heart and inflame it with eternal love.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Lewis deSoto’s multi-media works are informed by the artist’s long-standing interests—in anthropology, history, mythology, and religion—and his background. He was born in San Bernardino, California, is of Spanish and Cahuilla (Native American) heritage, and developed an interest in Buddhism as an undergraduate at University of California, Riverside (his major was Studio Art, his minor Religious Studies).

Having long considered the nature of consciousness near the moment of death, Paranirvana (Self-Portrait) was originally conceived by deSoto in 1999 shortly after his father’s passing. There are currently four versions of this work, each differing in color. This version—black with silver features—is the most recent (the first edition is tan, followed by a second in blue, and a third in gold).

The work’s title refers to the term parinirvana (spelled with an “i”): a Buddhist term commonly used to describe “nirvana after death.” Because this work represents the (living) artist, he felt that “para” nirvana (“para” meaning “resembling,” “near,” or “beyond”) would more aptly serve as a notion of the experience that this state is said to represent. It may also be interesting to point out here that, when inflated, the sculpture captures a suspended state, in effect portraying the moment between life and death.

- Puja and Piety, 2016