José Luis Cuevas

Mexican, 1933-

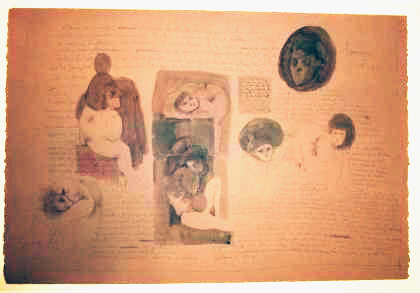

Desnudo y Manuscrito (Nude and Manuscript), 1962

ink on paper

15 1/2 x 22 5/8 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase, Donald Bear Memorial Collection

1963.14

A powerful first memory, he reports, is of a collection of puppets (“nuns, bullfighters, skeletons”) that hung from his crib. “All were broad of trunk and thin of limb,” as Crevas’s personages remain to this day. “They gave me my first notion of how the human body is put together.” But it was the art of Orozco, with its sinewy, mobile structure, that eventually taught Cuevas how to turn the dolls into his creatures of maimed flesh and poisoned blood that exist so disturbingly in a world divided between nightmare and tangible reality.

COMMENTS

José Luis Cuevas was born to a middle-class family in Mexico City in 1934 and started drawing at a very young age. From the beginning he began to focus his pen on the victims of society. An attack of rheumatic fever during childhood left him with a permanent mark of preoccupation with death. He wrote in 1973 that ever since he was a lad, he had befriended death as if it were a natural occurrence, and as a boy he had played with macabre toys. And now he drew death.

He was admitted to art school at the age of ten and at fourteen had organized his first exhibition, although no one came. However, success came early with his first gallery exhibit in Mexico City in 1953. He gained international fame while still in his twenties.

In addition to drawing, Cuevas read voraciously. Dostoevsky made an indelible impression on him, and he had a great affinity to Luis Bunuel. Much of Cuevas’s work appeared in serial form that was often inspired by books, though subjected to his highly personal interpretations rather than simply illustrating the work. For instance, he was so affected by reading Kafka’s work that he made drawings of himself as the cockroach of Metamorphosis.

In the 1950s he visited hospitals where he made drawings and did dissections of cadavers. He also drew portraits of prostitutes and the wretched children of the district of Nonoalco. In 1954 in an interview with Time magazine he lashed out violently against the Mexican muralists. He felt that in order for the post-World War II Mexican artists to assert themselves and establish their own individuality they had to declare their independence of the national tradition of mural painting and its didacticism. At the same time, however, Cuevas and other like-minded artists in the short-lived group called Nueva Presencia were in opposition to the Abstract Expressionist art of New York and the Informal painting in Paris.

In 1958 he traveled to South America and gave lectures against an indigenous style of art. The people of Lima, Peru, were greatly aroused, and he was challenged to a pistol duel. A year later he survived a major airplane crash in Brazil. In 1961 while traveling in Europe his life was again spared in an automobile accident in Italy. In the same year he exhibited at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

Traveling to Europe and working in Madrid, increased Cuevas’ temptation to tie his increasingly macabre and hallucinatory art to that the Goya, of the Caprichos. But the truest source of this element in his work is Mexican folk art, Mexican festivals for the dead, and, as described (necessarily by hindsight) in his autobiography, some of the things he saw from his window as a child.

Cuevas is Mexican not only by the geographical accident of birth but [also] presumably by some kind of emotional conditioning as well. But, again like them, he rejects the nationalistic spirit of the Rivera-Orozco-Siqueiros tradition of Mexicanism that is now dead as a stimulus to artists, although the mass of Mexicans, led by Mexican academic officialdom, still like to think of it as alive.

In 1954 Cuevas attained a celebrity rarely associated with a man of his age with his first presentation in the United States, at the Pan American Union. He was even then the artist that he is today: he had the same talent for capturing the anguished, the sordid and the sinister, seasoned at time with a strange dose of black humor. Then as now also he represented the best international tradition in draftsmanship, a plastic concept that goes back to Goya and to Spanish drawing of the seventeenth century, and that developed in Mexico under the influence of the vision of the world taken by the Indians before and after the Conquest.

The difference between the Cuevas of 1954 and the Cuevas of 1965 lies in the fact that in his earlier stage the artist, though thoroughly professional in his execution and mature in his conceptions, was still influenced by external reality, still dependent on his models. Always armed with a sketchbook, always on the lookout for a subject, as if he were a free-lance photographer, he was an eager, direct reporter of what he saw in the streets about him. The result was a series of mentally retarded children with swollen heads, a series of decaying prostitutes glimpsed through half-open doors and shutters, a series of fortunetellers, a series of patients from the national insane asylum. Cuevas already showed his searing line, his power of synthesis, and the richness of his emotional repertory. Clearly evident, however, was the presence of Mexican models, firm and unchanging. The artist’s respect for reality kept his fancy in check: it did not permit of distortion or disintegration. A truly gifted draftsman, he depicted the world about him with vigor, and at times with wonder. He was still, however, a slave to his subject matter.

Bibliography

José Gomez Sicre , Visual Arts Division, Department of Cultural Affairs, Pan American Union, April 1965, Washington, D. C.

José Luis Cuevas, Borgenicht Gallery, New York City

Compiled from SBMA Docent files by Loree Gold, typed for the docent website by Ralph Wilson, 2000

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

For José Luis Cuevas, a bout with rheumatic fever at the age of eleven sparked what would become a lifelong dedication to drawing and reading. He preferred the intimacy and directness that ink and watercolor offered over oil painting, and it was in his grandfather’s paper mill where he first became attached to working on paper. As a convalescent child, Cuevas observed from his bedroom window prostitutes, local beggars, the maimed and disfigured—social outcasts with whom he felt a kinship—and incorporated these figures in his work.

His deeply personal and introspective works on paper contrasted sharply with the grandiose, politically charged murals of Los tres grandes. Cuevas was a vocal leader of La ruptura generation of the 1950s and ’60s, which sought to break from the dominant legacy of Mexican muralism.

- SBMA title card, 2013