Eugène Delacroix

French, 1798-1863

Winter: Juno and Aeolus, 1856

oil on canvas

24 x 19 1/2 in.

SBMA, Museum Purchase, Ludington Antiquities Fund and Ludington Deaccessioning Fund

2013.41

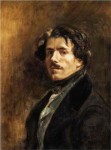

Eugène Delacroix, Self Portrait, c. 1837, Musée du Louvre, Paris

“The source of genius is imagination alone…the refinement of the senses that sees what others do not see, or sees them differently.” - Eugène Delacroix

"The question remains this — Christ’s boat by Eugène Delacroix and Millet’s sower are of entirely different workmanship. Christ’s boat — I’m talking about the blue and green sketch with touches of purple and red and a little lemon yellow for the halo, the aureole — speaks a symbolic language through color itself. Millet’s sower is colorless grey — as are Israëls’s paintings too. Can we now paint the sower with color, with simultaneous contrast between yellow and purple for example (like Delacroix’s Apollo ceiling, which is precisely yellow and purple), yes or no? Yes — definitely." - Letter to Theo, 28 June 1888

RESEARCH PAPER

Eugene Delacroix is considered to be one of the last great old masters. He is also often called the father of modernism. His roots were upper middle class and his politics leaned more toward the patrician than the people. “He had a reputation as a Bohemian but was meticulous in his craft.” (Pitcher) He can be thought of as a man of two worlds, a transitional pivotal figure in both his personal and artistic life.

He was born in Charenton-Saint Maurice, France, in the year 1798. His father was an Ambassador of the French Republic and his mother was from a family of an artistic and craftsman tradition. Both his parents died when he was young, and he was raised by an older sister who was herself the wife of a French Ambassador. Delacroix was born with connections, but he did not have great wealth on his own. It was important that he be successful not only in the Paris Salon but also in the marketplace.

In 1815 Delacroix started his artistic training in the classicist tradition with the painter Guerin. His eventual style, however, was more influenced by the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens whose paintings he would have encountered in the Louvre. In his early work he painted the more traditional religious and mythological subjects of the neo-classical tradition. As his work matured, however, it showed the influences of his travels, and his love of the English artists, notably Constable, and also of his love for English poetry and literature. As a result, his work broke away from the academic traditions of the time, and his painting style become more dynamic and emotional. He had a love/hate relationship with the Paris Salon, sometimes he was in favor and sometimes he was not, and he was often thought by some to be an untalented rebel. Fortunately, during the down times, he had the patronage of the King and received private commissions that allowed him to survive as an artist.

“Winter: Juno and Aeolus” is a wonderful example of his style. Delacroix was commissioned by a private collector to paint four different paintings, each one depicting a different season of the year (The Seasons). This painting is the preliminary oil sketch for the Winter painting. Even though this is not the final painting “the sketch represents a scene of greater energy and dynamism than the later painting” (75 in 25, p.154) and gives great insight into his technique.

In looking at the painting, you are immediately drawn to the figure in the upper right. This is the goddess Juno. She is looking down at Aeolus, the God of Wind. She is beseeching him to release the force of the wind against the Trojan Fleet because Paris, also a Trojan, picked the goddess Venus as the most beautiful. In this painting one can see Delacroix’s trademark style, his use of vibrant emotive colors, swirling background, and dynamic movement. Every form has color, objects as well as shadows, from the blue green sea, the violet of Aeolus’s costume to the reddish pink of Juno’s robes. Even the dark brown rocks and grey storm clouds are flecked with green and gold.

He has created a delightful balanced and harmonious composition as your eye follows Juno’s gaze down to Aeolus, then across the figures surrounding him (possibly his entourage) then up to the golden area below Juno’s feet (where perhaps a battle at sea is occurring) and then back to Juno. He creates this balance and movement not only through the placement of figures, but also through his use of expressive brushstroke and color. Delacroix truly understood color and the effect that each color had on surrounding colors. “The greater the contrast, the more brilliant the effect.” (Delacroix Journal p. 146). This idea is clearly represented throughout the painting, especially in the way the bright red of Juno’s robes pops out against the green and blue grey of the surrounding clouds and sky.

The painting’s Mythological subject matter would have pleased the pious clarity preferred by the neo-classicists of the Paris Salon, but Delacroix was not known for his subtle palettes, calmness or clarity of line. What he believed was most important in art was passion, appetite, spontaneity and that the feeling of the artist come through from an intense engagement in life. Although he was not always the darling of the Salon, his work influenced many artists of the time and in later years. “The Modern Movement wouldn’t have happened without Delacroix. His influence on the Impressionists, Post Impressionists and Modern Art’s most celebrated pioneers is undeniable.” (Pitcher) A short list would include Manet, Monet, Cezanne, Van Gogh, Kandinsky and Picasso.

Delacroix was also a renowned writer, and his Journal is thought to be a masterpiece in itself. It is therefore fitting that some of the last words he wrote before he died were: “The first merit of a painting is to be a feast for the eyes.”

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Susan Lowe, 2020.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Websites:

Davis, Ben, “How Delacroix’s Revolutionary Art was Forged in the Fires of Counterrevolutionary France, news-.artnet.com, October 2, 2018

https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/delacroixs-revolutionary-art-forged-fires-counterrevolutionary-france-1358836

Picher, Laura, “Coldplay, Picasso and Lady Liberty: How Delacroix Changed Art Forever”, Observer.com, September 12, 2018

https://observer.com/2018/09/delacroix-influences-coldplay-picasso-statue-of-liberty-the-met/

National Gallery of Art, Biography of Eugene Delacroix, nga.gov

https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1221.html

Books:

“75 in 25, Important Acquisitions at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art 1990-2015”, publisher Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2016

Delacroix, Eugene, “The Journal of Eugene Delacroix”, Phaidon Press, third edition reprint, 2004

The final tableau, São Paulo Museum of Art

COMMENTS

When Van Gogh moved to Paris in 1886, he returned again and again to the Louvre to view works like “The Barque of Dante”, Eugene Delacroix’s grand vision of artistic determination. Depicting a scene from lnferno, Delacroix painted Dante crossing the River Styx, teeming with tormented souls, set against a background of the City of the Dead—but maintaining his equilibrium with the help of the Classical poet Vergil. In the same galleries where Van Gogh ignored so many other works, he sought out lesser-known images by the Romantic master. He also went repeatedly to the Church of Saint-Sulpice to see Delacroix’s great altarpiece “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel”. “Delacroix was his god,” a fellow student at an art school that Van Gogh attended in Paris would later recall, “and when he spoke of this painter, his lips would quiver with emotion.”

Van Gogh’s reverence was in part for Delacroix’s mastery of complementary colors, which Van Gogh had carefully studied in the writings of the important color theorist Charles Blane. All of nature was composed of only three “truly elementary” colors, according to Blanc: red, yellow, and blue. The concept is familiar to us today as the color wheel. Combining any two of these “primary” colors produced one of three “secondary” colors: orange (red + yellow), green (yellow + blue), or violet (blue + red). One could then pair a primary color with the secondary color created from the two other primaries. Blanc referred to the relationship between these pairs of unrelated colors as “complementary”—they completed each other-—but he found in their interaction a fierce struggle for separation and supremacy: blue against orange, red against green, yellow against violet. The eye reads their struggle as “contrast.” The starker their opposition—the closer their proximity, the brighter their tone—the more violent the struggle and the more intense the contrast.

Few artists commanded the intensity of Blanc’s complementary colors like Delacroix. In a vanguard art world filled with sectarian reviews and fire-breathing rhetoric, with atelier debates and café chatter, Van Gogh clung to the view that complementary color was the one true gospel and Delacroix its truest prophet. Delacroix “spoke a symbolic language through color alone,” he said, and through that language, he expressed “something passionate and eternal.”

But his appreciation of Delacroix was deeper than that. To Van Gogh, Delacroix ranked as a “universal genius.” Van Gogh loved him not only for his daring and expressive use of color and his bravura brushwork—for seeing the poetic possibilities in an intentionally “unfinished” image—but also for his ability to explore the fullest range of the artistic imagination and to convey the deepest possible artistic sentiment. Delacroix “paints humanity,” Van Gogh said. To his friend Anthon van Rappard, Van Gogh praised the great Romantic artist in the language of Romanticism: “When Delacroix paints—it’s like a lion devouring a piece of meat.” To his friend Emile Bernard, he added, “I love the closing words of [the poet Armand] Silvestre, I think it was, who ends a masterly article like this: Thus died—almost smiling—Eugene Delacroix, a painter of high breeding—who had a sun in his head and a thunderstorm in his heart.”

Even as he struggled through the storm of new artistic movements around him, Van Gogh never lost reverence for Romantic art—and for the Romantic sublime. “Delacroix, Millet, Corot, Dupré, Daubigny, Breton, 30 more names,” Vincent insisted, “do they not form the heart of this century where art is concerned, and all of them, do they not have their roots in romanticism, even they surpassed’ romanticism? Romance and romanticism are our era, and one must have imagination, sentiment in painting. Happily, realism and naturalism are not free of them.”

- Steven Naifeh, Van Gogh and the Artists he Loved, New York: Random House, 2021, 99-100

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This oil sketch was done as a preparatory step for one of four decorative panels commissioned for a private home, organized around the theme of the four seasons. Echoing earlier Rococo masters, Delacroix summons the idea of winter through the mythological story of the Roman goddess Juno, who is shown commanding the god of the winds, Aeolus, to unleash violent storms intended to destroy the Trojan warrior Aeneas and his ships.

Delacroix was in the habit of relying upon studio assistants to accomplish large scale interior decorations for public buildings, such as the Chambre des Députés of the Senate in Paris. Sketches like this by the master would have served the assistant as the model by which to execute the corresponding large-scale version. This oil sketch exhibits a painterly freedom typical of Delacroix’s late work, which anticipates the lack of finish characteristic of the Impressionists. Form is suggested rather than fully defined, as in the swirl of teal green pigment emanating from Juno’s cloud that fittingly conjures the shape of her attribute, the peacock.

- Through Vincent's Eyes, 2022

This oil sketch was done as a preparatory step for one of four decorative panels commissioned for a private home, organized around the theme of the four seasons. Echoing earlier Rococo masters, Delacroix summons the idea of winter through the mythological story of the Roman goddess Juno, who is shown commanding the god of the winds, Aeolus, to unleash violent storms intended to destroy the Trojan warrior Aeneas and his ships.

Unlike the corresponding large-scale version, this sketch is entirely by Delacroix, and exhibits a painterly freedom not found in the labored surface of the "finished" painting (illus.), on which he collaborated with his student, Pierre Andrieu.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery, 2014

Delacroix is considered the greatest colorist of the first half of the 19th century. By emulating the brilliant palette and dynamic compositions of his idol, the 17th-century Flemish painter, Peter-Paul Rubens, he almost singlehandedly displaces the restrained rationalism and muted palette associated with the earlier school of Neoclassicism. Delacroix was admired by Monet and the Impressionists for his willingness to break with academic convention by wielding opulent color and bravura brushwork to communicate the emotional intensity of the dramatic subjects to which he was attracted.

This oil sketch is a prime example of the luminosity the painter was able to achieve in the late work. It was done in a preparatory step for one of four, large decorative panels organized around the theme of the four seasons, commissioned by a wealthy textile manufacturer named Jacques-Félix Frédéric Hartmann (1822-1880). Echoing such earlier Rococo masters as François Boucher, Delacroix summons the idea of winter through the mythological story of the Roman goddess Juno, who is shown commanding the god of the winds, Aeolus, to unleash violent winds intended to destroy the Trojan warrior Aeneas and his fleet of ships.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery, 2013