Eugène Delacroix

French, 1798-1863

The Last Words of Marcus Aurelius, n.d.

oil on canvas

25 5/8 x 31 3/4 in.

The van Asch van Wyck Trust

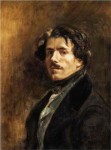

Eugène Delacroix, Self Portrait, c. 1837, Musée du Louvre, Paris

"What moves those of genius, what inspires their work is not new ideas, but their obsession with the idea that what has already been said is still not enough." - Eugene Delacroix

Lyon monumental version, 1845

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This painting has recently been attributed to Delacroix and represents an exciting addition to the corpus of the Romantic artist’s output. The dying emperor Marcus Aurelius is shown pleading the case before his friends and fellow Stoic philosophers for his dissolute son Commodus, who ultimately goes on to become as reviled for his dictatorial rule as his venerable father was revered. A variation, rather than a straightforward repetition of the monumental version exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1854, in this easel-sized painting, Delacroix subtly reinterprets the subject, softening Commodus’s effeminate features and playing up his youthful beauty, thereby soliciting our compassionate identification for a dying father’s anxiety over his young son’s fate. In comparison to the more theatrically-lit prime version, the scene seems to be suffused by the rosy light of dawn, perhaps in response to art critic Charles Baudelaire, who commented upon the poetry of Delacroix’s symbolic idea of Commodus, in his fiery red robe, as the rising sun of the future.

- Ridley-Tree Reopening, 2021

The dying emperor Marcus Aurelius is shown pleading the case before his friends and fellow Stoic philosophers for his dissolute son Commodus, who ultimately goes on to become as reviled for his dictatorial rule as his venerable father was revered. A variation, rather than a straightforward repetition of the monumental version exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1854, in this easel-sized painting, Delacroix subtly reinterprets the subject, softening Commodus’s effeminate features and playing up his youthful beauty, thereby soliciting our compassionate identification for a dying father’s anxiety over his young son’s fate. In comparison to the more theatrically lit prime version, the scene seems to be suffused by the rosy light of dawn, perhaps in response to art critic Charles Baudelaire, who commented upon the poetry of Delacroix’s symbolic idea of Commodus, in his fiery red robe, as the rising sun of the future.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery, 2016

This painting has recently been attributed to Delacroix and represents an exciting addition to the corpus of the Romantic artist's output. The dying emperor Marcus Aurelius is shown pleading the case before his friends and fellow Stoic philosophers for his dissolute son Commodus, who ultimately goes on to become as reviled for his dictatorial rule as his venerable father was revered. A variation, rather than a straightforward repetition of the monumental version exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1854, in this easel-sized painting, Delacroix subtly reinterprets the subject, softening Commodus's effeminate features and playing up his youthful beauty, thereby soliciting our compassionate identification for a dying father's anxiety over his young son's fate. In comparison to the more theatrically lit prime version (illus.), the scene seems to be suffused by the rosy light of dawn, perhaps in response to art critic Charles Baudelaire, who commented upon the poetry of Delacroix's symbolic idea of Commodus, in his fiery red robe, as the rising sun of the future.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery, 2014

This painting is a new addition to the [Marcus Aurelius] oeuvre... While unsigned, we believe it is unquestionably by the hand of Delacroix. A variation, rather than a straightforward repetition of the Lyon monumental version, in this easel-sized painting, Delacroix subtly reinterprets the subject, softening Commodus‘s effeminate features and playing up his youthful beauty. Overall, there is a tighter focus on just four figures, instead of all nine. In comparison to the more theatrically lit prime version, the scene seems to be suffused by the rosy light of dawn, perhaps in response to the art critic, Charles Baudelaire, who commented upon the poetry of Delacroix‘s symbolic idea of Commodus as the rising sun of the future.

In the artist‘s own words, he sought to represent the following: "The perverse inclinations of his son, Commodus, having already been manifested, in a dying voice, the emperor pleads the case for the youthfulness of his son to some of his friends, who were Stoic philosophers like himself. But their mournful attitude clearly shows that these urgings are in vain and anticipates the dark future of the Roman Empire." As predicted, Commodus turns out to be every bit as dissolute as Marcus Aurelius was virtuous, undoing his father‘s advancement of political consensus as the necessary foundation for imperial Roman rule.

- Delacroix and the Matter of Finish, 2013