Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas

French, 1834-1917

Ballet Dancer Resting, 1900-1905 ca.

charcoal on cardboard

19 5/8 x 12 1/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Wright Ludington

1941.1.7

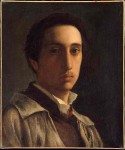

Edgar Degas, Self-portrait, Oil on paper, ca. 1855–56

RESEARCH PAPER

Edgar Degas was born in Paris in 1834, the eldest of five children. His father was a banker. His mother came from a French Creole family of New Orleans. Some members of the Degas family living in Italy and France altered the name to De Gas in order to sound more aristocratic. Separated, it indicated a name derived from land holdings, but sometime after 1870 Edgar went back to using the original spelling.

Degas is described in the Encyclopedia Britannica as, "one of the greatest draftsmen in the history of Western art who is an acknowledged master of drawing the human figure in motion." Degas himself is quoted as saying, "I assure you that no art was ever less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and study of the great masters; . . . of inspiration, spontaneity, temperament ... I know nothing."(Vol. III p.435)

He created a style anchored in tradition and yet appropriate to subjects taken from modern life. His father was a cultured man with a taste for music and painting. From an early age, Edgar was taken to museums. When he was eleven years old he entered the Lycee Louis-le-Grand in Paris where he remained for all his school years. After a brief fling at studying law, he entered the studio of Barrias and began to copy pictures at the Louvre. In 1858 he went to Italy. In addition to copying the masters in Rome and Naples he went to Florence where he stayed with his uncle, Baron Bellelli. In Orvieto, he copied from the frescoes by Signorelli, whose work he admired. Degas said he was inspired by Signorelli’s "love of stir and bustle.” His education was therefore a thorough one, and Edgar applied himself with great dedication.

Although France was undergoing considerable political unrest in 1870 due to the Franco-Prussian War, Degas chose themes, which were tuned to scenes of contemporary life. He covered a surprisingly wide range of social strata, which marks him apart from the academic history painters. Much of his work reflects the new prosperity of the times. The Paris fashion industry was flourishing and Degas drew images of milliners. There was also a growth of the service industries to serve the needs of the bourgeoisie. Degas offered insight into the worker’s lives in his portrayal of laundresses, many of whom he sketched as they bent over an ironing board. Other scenes of daily life show nude women in the act of bathing. Never denigrating his models, the reality of their awkwardness was more effective than the conventionally posed nudes of the past.

The increasing affluence of the middle class fostered social diversions. Some of Degas’ works depict life at the racetrack. Horseracing was newly imported from England and very fashionable. Degas chose to show gatherings related to the action of the horses or casual interludes associated with racetrack life. However, he is best known for his themes centered upon the world of ballet. His artist’s hand caught the dancers either performing before a blaze of artificial light or in rehearsal. The latter included seemingly ungainly poses of dancers at rest or at bar exercises. These figures convey the feeling of a split-second moment of action, which might have been snapped by a camera. Indeed, Degas was strongly influenced by the advent of photography and was also a photographer.

Because of these unexpected viewpoints and perspectives combined with his use of light and unmodulated colors, Degas is associated with the Impressionists. He drew inspiration from Japanese prints. The Impressionists were familiar with them as early as the 1860s. Along with his friend, Claude Monet, Degas used other techniques borrowed from the Japanese such as asymmetrical compositions and the use of cropping. He particularly favored the Japanese objectivity in his portrayal of figures, seldom individualizing a face except in portraits. These similarities with Impressionistic characteristics and his participation in the first Impressionist Exhibition in 1874, contributed to his often being labeled an Impressionist. His friends included not only Monet, but Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, and Manet. Degas exhibited in all but one of the eight Impressionist shows from 1874 to 1886.

However, the linear technique of the older generation represented by Ingres had an influence on Degas. When he met him in 1855. Ingres told him, "Draw lines, young man, many lines from memory and from nature; it is this way that you will become a good painter." (qtd. In Gardner p.699) Although Degas’ lines were freer and looser than those of Ingres, he became a superb master of line. Some critics feel he should not be identified as an Impressionist painter. His designs do not cling to the surface of the canvas, as do those of Manet and Monet. Rather, Degas preferred to take the viewer deeper into the picture plane with linear devices. He had no interest in the plein air effects of light and atmosphere on landscape and water. In his figures his preoccupation was with form. His portrait of the painter, Jacques Tissot, conveys something of Degas’ desire to link the old with the new. Tissot is shown in a relaxed pose in his studio as though he might be in an artistic discussion. Hanging on the wall behind him are copies of old master paintings along with contemporary and oriental works. The assumption can be taken that both Tissot and Degas shared an interest in all styles and periods of art.

For his media he used oil, watercolor, chalk, pastel, pencil, and etching. He was particularly fond of pastels, and used them side-by-side. Chalk muddies when mixed. As a perfectionist he liked to add final touches to his pictures no matter how finished they were. Most of them were executed on tracing paper. To correct what he did not like he would make tracing after tracing. Then the framer would glue them onto a bristol board. For a fixatif he used a special preparation made for him by an Italian painter, Chialiva. The secret of this has died with Chialiva, but it has been an important aid in preserving Degas’ work.

In his youth he used graphite. His admiration for Ingres may have contributed to his preference for this medium, but from the beginning he differed from the style of Ingres in the expressive feeling he imparted to his figure forms. Due to the unfortunate deterioration of his eyesight in the mid-eighties he slowly abandoned graphite. The lines appeared too pale to him. Increasingly he used greasy crayons and vine charcoal. This method facilitated the successive tracings, which made for easier corrections. His pastels occupied the last productive period of his life, and his repeated tracings resulted in the gradual enlargement of his drawings.

With the onset of blindness he turned to sculpture. Oddly, he never got beyond the wax or clay stage. This may have been due to his extreme criticism of his work. He said, "The only reason I made wax figures ....was for my own satisfaction, not to take time off from painting or drawing, but in order to give my paintings and drawings greater expression, greater ardor and more life. None of this is intended for sale." (qtd. In Knopf. Cited in Degas Sculpture, Thiebault-Sisson, 1921).To the admirers of Degas in our day, the many reproductions of his "Little Fourteen Year Old Dancer" made in 1881 continue to bring pleasure. She was an innovative bronze sculpture of mixed-media which incorporated ribbon, tutu, and hair.

The SBMA has three delightful drawings by Degas which offer insight into his process of perfecting forms. "Ballet Dancer at Bar Exercise" is a work in pencil on paper, the gift of Wright Ludington. It has an approximate date of 1885. Clearly visible are the corrections of the artist as he struggled to convey the instant of the dancer’s stretching movement as she sinks and rises in this difficult body position. According to recorded remarks of Degas, he was dissatisfied with the right arm. Perhaps as a perfectionist this did not please him, but the drooping arm seems to convey the truth of the moment. Her right hand has perhaps become slack in its grip on the bar, and the arm is tiring. This touches the empathy of the viewer.

"Ballet Dancer Resting" is a charcoal drawing on tracing paper, also a gift of Wright Ludington. It has a date of ca. 1900. In his later years, Degas reworked some of his sketches of figures, which might have been once intended for part of a scene but now became a self-contained statement and a jewel in itself. He often signed and framed them. In this work the star-burst composition stands out in charcoal lines which vary from strong to delicate. The body twists, the splayed tutu, the triangles formed by her elbows, all create an abstract beauty of form. Into this pattern is fused the quiet pulse of life and sentiment. It is sensed in a flow of line, which ripples from the dancer’s long hair and is echoed in the undulating curves of her body muscles.

Again, Degas has grasped a moment of reality in the life of a professional dancer. In another second she may have moved. Now that photography could capture the un-idealized world, the artists were forcing art lovers to see beauty in the un-posed. The little dancer is fatigued. From the lines of her raised arm resting against the wall, down to the shadow between her shoulder blades, her pose tells a story. Her tilted face and upper arm are emphasized by strong highlighting. This suggests a possible reflection from stage-lights as she waits in the wings. Resting her head against her arm, her stance has become lax, thus making the viewer aware of her effort to regain muscle strength before continuing. The contrast between the smiling performer and the off-stage world is clear.

In Degas’s sketches of horses, as in his human figures, he shows that he was a master of fore-shortening and modeling. The SBMA owns a work on paper entitled, "Two Standing Horses." It is in charcoal and is signed. The date is ca. 1880. Although the horses are in repose, their forward-pointed ears and alert head positions give them vitality. Their lean lines of bone and muscle make them almost sculptural. However, for all their bronze-like quality, they seem to be more like living creatures than the fashionable horses shown in English prints so much in vogue at the time. Some of his models of horses have been cast in bronze. By 1904 his sight was so limited that he could only work on sculptures and very large compositions. Sadly, he became increasingly introspective and reclusive. He never married. In 1914 some of his paintings were accepted at the Louvre in the Camondo Collection. He could now look back on many productive years. Never discouraged by difficulties, he had enjoyed new tasks and progress. Up to the end he was aware of new developments in art. Toulouse-Lautrec, Gaugin, Van Gogh, all admired him as he admired them. He died in 1917 and was buried in the family vault in Montmartre cemetery. His artistic legacy was consistent with the dawning age of the motion picture in its break with the static perfection of the academic style. The world he recorded was a comprehensible one, which reflected the flow of life.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council, July, 2001, by Jean Baechlin

Also in SBMA (?) collection, Little 14 Year Old Dancer, 1881, Bronze.