Stuart Davis

American, 1894-1964

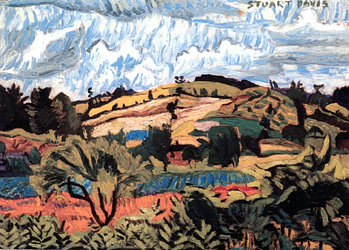

Yellow Hills, 1919

oil on canvas

24 x 30 in.

SBMA, Gift of Heyward Cutting

1980.73

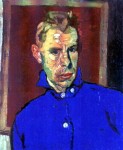

Stuart Davis, Self-Portrait, 1919, Oil on canvas, Amon Carter Museum

In his many musings and writings Davis revealed his desire to turn away from realism and more towards abstraction. He stated in 1942 that "My early landscapes showed enthusiastic emotion about the color-texture-shape-form of association entities such as sky-sea-rocks-figures, vegetation. The purpose was to make a record of things felt and seen so that the total association of the moment could be experienced." And then in 1943 he finally decided after some soul-searching "So let’s be done with all this mid-Victorian nonsense of looking for familiar images and visual effects in painting. From now on the painting must stand on its own legs as pure-color position, solidity, symbols and textures." - Stuart Davis

RESEARCH PAPER

"Yellow Hills", an oil painting by Stuart Davis, was executed on location in an area that is unknown to us. It was done early in his life (1919) while under the influence of the styles of a group of painters known as "The Ashcan School," or variously "The Eight". Several of these artists such as Robert Henri, George Luks, William Glackens, and Everett Shinn, who were newspaper artists, were acquaintances of Davis’ father, who was art editor of the Philadelphia Press.

Stuart was born in Philadephia in 1894 into an artistic family. His mother was a sculptor and his father, besides having some art training himself, was in close contact with many of the well-known and controversial artists of the day. Very early in Davis’ life his parents moved to New Jersey, where his father accepted a position with the Newark Evening News. At about that time Henri opened his art school in New York. Davis was able to convince his parents to permit him to enroll there before finishing his high school studies. There he came in contact with and was strongly influenced by John Sloan among others who inculcated, in him, a desire for self-expression rather than strict adherence to academic rules. He was also encouraged, at this time, to move among the people in the streets, saloons, and theaters to seek out subject matters of contemporary life. His work matured quite rapidly and in 1913 he was permitted to submit five watercolors to the famous Armory Show in New York. During this period he also did some illustrations and cartoons for Harper’s Weekly and the Masses.

"Yellow Hills" was executed in 1919 during the period when he was strongly impressed by the modernist European artists at the Armory Show. It was done in a manner similar to Van Gogh using a heavy, impasto technique with a brush loaded with color albeit in somewhat muted tones. The painting consists of horizontal bands of oranges, blues, yellows and greens of various hues done with short, bold emotional strokes. The forms are subtly suggested so that in order to make them recognizable one has to move back some distance from the painting. Another work similar in technique to "Yellow Hills", also done in 1919, called "October Landscape" creates the same mood and shows analogous forms as the former painting.

The Armory show was a strong turning point in Davis’ career as he stated "I responded particularly to Gauguin, Van Gogh and Matisse, because broad generalizations of form and non-imitative use of color were already practiced within my own experience.

"I also sensed an objective order in these works which I felt was lacking in my own. It gave me the same kind of excitement I got from numerical precisions of the Negro piano players in the Negro saloons and I resolved that I would definitely have to become a modern artist."

It was this show that caused him to become disenchanted with the Henri philosophy of placing too much emphasis on subject matter. It was here, in Henri’s school, that Davis was introduced to the use of color and design systems and art theories. This impelled him to seek methods of solving his own problems by attempting to reduce various aspects of visual nature to a logical, rational system.

Thus, in 1928, he departed for Paris to gain first-hand knowledge of European methods. Davis claimed that he learned much about composition in Paris and that the year in France was "one outstanding event in my artistic life". He absorbed and used many cubist ideas in his paintings and was strongly affected by Picasso, Braque, Gris and Leger. He incorporated many of these styles in conjunction with American elements used in his later works.

Stuart Davis fused his modernist style with the American Scene in an exemplary manner and his handling of subject matter was "not imitative or realistic but analogical…without identity to its subject". He railed very strongly against the American Scene painters Benton, Curry and Grant Wood and accused them of no understanding of the real achievement of 20th century art.

Davis was one of the leading American modernists who through his voluminous writings, published and unpublished, created a large mass of intellectual musings that records the esthetic, philosophical and political issues of a whole range of modernist art theory. He finally forged his personal style "that eschewed the intellectual elegance of cubism in favor of the bold, brash language of popular Americana" as Diane Kelder expressed it. He was strongly innovative and receptive to changes in ideas and styles in the search for an individual perception, but, always within the parameters of his own intuitive sense. This resulted, finally, in an art devoid of natural subject matter but instead supplied us with a personal iconography exacted from his American experiences.

Bibliography

1. The Brooklyn Museum. Lane, John R. Stuart Davis, Art and Art Theory.

Jan. 21- Mar. 19, 1978

2. Goosen, E.C. Stuart Davis. New York: George Braziller, 1959.

3. Kelder, Diane. "Stuart Davis". New York: Praeger, 1971.

4. Lane, John R. "Stuart Davis and the Issue of Content in the New York School of

Painting," Arts Magazine. Vol. 52, No. 6, Feb. 1978, p154-7.

5. Museum of Modern Art. James Johnson Sweeney. "Stuart Davis".

New York, 1945. repro. p.12, 13 and 35.

6. Myers, Bernard S., ed. McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Art. New York: McGraw-Hill

Book Co., 1969. Vol. 2, p. 221-2.

7. Walker Art Center, "Stuart Davis", June 1-Aug. 15, 1957.

8. Cutting, Mr. Heyward, Letter of Acknowledgement of Acquisition from Donor, 1981.

______________________________________________________________________

ADDITIONAL RESEARCH PAPER

On first glimpse one could easily mistake "The Yellow Hills" for an undetected Van Gogh. The vivid landscape seethes with dynamic action. One can feel the knife going from palette to canvas back and forth in a restless rhythm such as might be heard in a jazz riff. There is no fixed focus nor the deliberate perspective found in most "landscapes". The golden hills, a brilliant ocherous patch are only a band among the striated masses of color, a patched quilt-like effect of vivid oranges, greens, and yellows to earth tones. Davis was merely 19 when he painted it!

The railroad track in the immediate foreground suggests the scene is as if viewed from a railroad car, with the passing mass of hot orange and pronged scrub-oak. Greenery elsewhere is less defined, as if a nod to woods, shrubs, plant life. Blobs of green are indicated with superimposed black brush strokes to suggest trunk and branches, much as a child might add. In the lower third of the canvas is a long stretch of vivid turquoise with vertical strokes, a stream? Garden plots? This is abstract work inspired by Post Impressionism, Van Gogh, the Fauves, and perhaps even the German Expressionists.

In the upper third is a skyscape with an unlikely massing of clouds heavily impastoed in thick whites, against blues/greens in bold hatch-like strokes threatening a downpour that would turn the golden hills back to green. But to the right the sky softens with some cumulus clouds drifting gently away in the distance.

Over all the work has an animated emotionality achieved by a brush charged with energy and loaded with equally bold colors thickly imposed against each other with little or no blending. Davis leaves the mixing of these striations of vibrating colors to the eye of the viewer, to blend or not to blend together. The viewer discovers, however, upon stepping back, a room’s length away that these patches of paint swirl into a thickly rendered and most recognizable landscape.

Indeed, "The Yellow Hills" is not the kind of American landscape as was so romantically painted by The Hudson River School by such artists as Church, Bierstadt, Inness, or Eakins, rather, it’s a fine example of "expressionistic naturalism with broad generalizations of form and non-imitative use of color...the paint texture and stroke take on a fauve freedom." [Stuart Davis, Memorial Exhibition 1894-1964, Smithsonian Institute.]

While recognizing the great contribution made by the Post-Impressionists, the Fauves, and the Cubists and greatly influenced by their work in the historic Armory Show of 1913 which afforded many Americans their first encounter with European modernism, " Davis could never, except in sporadic exercises (as in the ‘almost Van Gogh’ here) simply imitate their styles." (Ibid). "The saturated colors make everything seem near, so we experience this scene both in the intimacy of its detail and as a vista from the level of the railroad tracks, of whose ties are visible at the bottom of the composition." [James Johnson Sweeney, Stuart Davis, exhib. Cat. New York: The Museum of Modern Art]

According to Hilton Kramer, Davis was greatly affected by the Armory Show which turned him into a modernist. "Post Impressionist color, especially in the work of Van Gogh, had the most decisive long-term impact on his artistic thought. A Self Portrait that he painted in 1919 with its electric blue shirt and bright red lips in a yellow face, set against a darker red monochrome canvas is at once an acknowledgment of Van Gogh’s influence and a preview of Davis’ later, more abstract style." [Hilton Kramer "Late-Cubist Davis, An Abstract Master to the End" The New York Observer January 16, 20003]

While the biographical data on Stuart Davis for the year 1919 record his move to Greenwich Village, and of his passing the summer in Tioga, Pennsylvania, "In Yellow Hills we see a scumbled sky like that observed in the painting, Setting Sun Tioga, PA....The handling of colors and texture of a deliberately wielded paint brush suggest it was executed in Gloucester, an artist’s colony that he frequented in the Fall of 1919." [Sims, Lowery Stokes: STUART DAVIS; Metropolitan Museum of Art publication] "Gloucester images remained part of his work until the end of his life...Davis came to Gloucester for the first time in the summer of 1915 and returned almost every summer until 1934. His development - from post-Impressionist through the style he called "optical geometry" - can be traced in his Gloucester landscapes and harbor scenes....Life in Gloucester centered around a group of close friends which included John Sloan and Paul Cornoyer among others. [Cape Ann Historical Museum "Stuart Davis in Gloucester" June 1999, article in Resource Library Magazine: www.cape-ann.com).

Stuart Davis grew up in an artistic environment. His father was art director of a Philadelphia newspaper who had employed as illustrators William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan, all of whom achieved artistic renown. Helen Stuart Foulkes, his mother, was a sculptor. By age 16, he was studying in New York with Robert Henri. [note Robert Henri’s 1910 Derricks of the North River in the S.B.M.A. collection]. In 1913, at age 19, he was the youngest artist to be represented in the historic Armory Show in N.Y. affording him his first encounter with European modernism. No less than five of his paintings were on display!

While Post-Impressionist colors of Gauguin and Van Gogh were hugely influential, after 1919 he was to move away from Post Impressionistic landscapes toward acts of more pictorial daring. In his writings he wrote of his purpose "to make a record of things felt and seen so that the total association of the moment could be experienced." [Pearlman, Joseph "Stuart Davis" docent research paper, 3/1983; S.B.M.A. artist-files]

Immersed in Greenwich Village life, he had contacts with literary magazines as a cartoonist illustrator. A drawing, Gloucester Terraces, was selected by the poet William Carlos Williams to illustrate a new collection, Kora in Hell: Improvisations His art also appeared in other little magazines, including the well known and esteemed DIAL.

By 1921 he was doing mixed media collages which came to have great commercial appeal. He wanted his art to be POPular, both in its clearly recognizable subject matter and in its immediate appeal to a broad audience much as advertising sought to do. Long before Sister Corita, or Kenneth Patchen’s celebrated works combining images with words, Davis was interfacing words and images in original juxtapositions that make his work so contemporary and recognizable.

His career encompassed many of the schools and movements that shaped American art of the 20th Century, producing works that managed to span the divides between them. From work as a cartoonist-illustrator for a left-wing periodical, "The Masses, to Harper’s Weekly," to working as a cartographer for Army Intelligence, and in his celebrated advertisements for Fortune and Time magazines. He evolved into a cubism-based, but all-American style of abstraction which further developed to incorporate signage, and other commercial motifs that clearly prefigured the iconography of PoP art. Throughout the 1940's and 50's, his illustrations for the Container Corporation were a part of the commission of a series–"advertisements made classy by the involvement of leading artists." [Hills, Patricia Stuart Davis 1956]. Unlike many of his Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, Davis was not a snob about commercial ventures. He went so far as to "join the faculty of the Famous Artists School in Westport, an art correspondence school that advertised itself on matchbook covers"! [ibid]

Davis identified the "soul of America" in the balanced integration of composition and improvisation that is the counterpart to that other unique art form, American jazz. In her book Patricia Hills calls the introductory chapter, "The Making of a Hip Modernist" She writes, "He identified with the urban America of everyday working people and with a culture infatuated with technology, consumer goods, and packaging, one that celebrated the small-time entrepreneur and at the same time responded to the rhythms of popular music and jazz." In one of his many journals, he characterized his own paintings as "color-space compositions celebrating the resolution in art of stresses set up by some aspects of the American scene."

[Kachur, L. & Wilkin, K. The Language of Stuart Davis: The Amazing Continuity.] His famous work, ‘Swing Landscape,’ alludes to swing music, from which Davis, a great lover of jazz, drew inspiration for his upbeat style of painting." [Stokstad, Marilyn Art History Vol. 2].

"The Yellow Hills" is an S.B.M.A. treasure, it represents an early stage of Stuart Davis’ artistic development. Later he would look to the city to combine the icons of the American culture. "Things which have made me want to paint...skyscraper architecture;...chain store fronts, and taxicabs, electric signs,...the brilliant colors on gasoline stations... fast travel... kitchen utensils; movies and radio; Earl Hines hot piano and Negro jazz music in general." [Wilkin, K. Stuart Davis in Gloucester].

We’re much indebted to Heyward Cutting for giving us this bold and brilliant painting, important enough to be reproduced in the book, Stuart Davis, published by the Smithsonian. It prefigures the impressive and distinctive body of work that was to follow it.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council

By Josie E. Martin, March 21, 2003

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnason, H.H.: Stuart Davis Memorial Exhibition (catalog) Smithsonian Publication 1965

Goosen, E.C.: Stuart Davis New York; George Braziller 1959

Hills, Patricia: Stuart Davis; National Museum of American Art 1996

Kachur, L. & Wilken, K.: The Amazing Continuity the Drawings of Stuart Davis; Harry Abrams 1992

Sims, Lowery Stokes: Stuart Davis; Metropolitan Museum of Art 1991

Stockstadt, Marilyn: Art History Volume II; PERIODICALSCape Ann Historical Museum: "Stuart Davis in Gloucester"

Kramer, Hilton "Late Cubist Davis, An Abstract Master’s Right to the End"; New York Observer

Jan. 16, 2003*

The Masses, November 1913 issue illustrations by Stuart Davis

GUIDE BY CELL

Guide by Cell Script

Sara Bangser

Considered a leading American Modernist painter and print maker, Stuart Davis, rightly brings us a magnificent compendium of artistic creativity spanning 70 years.

“Yellow Hills” was painted in 1919 when Davis was just 25 years old. The breadth of his career evolved enormously from this dynamic landscape. Here are the beginnings of certain themes that Davis expanded on through the decades. With the train tracks anchoring the foreground, Davis sets the rural scene as emanating from urban life outside the frame.

The natural elements of the painting are quite representational. Notice how the dark palate and deliberate laying down of pigment sets up an underlying energy and tension. Davis deliberately illustrates movement and ‘urgency-of-the-moment’ with the horizontal bands of natural landscape coloring. However, the somewhat muted coloration does not diminish the urgency that Davis wishes to share with the viewer.

On closer inspection his short, bold, brush strokes and thick impasto technique were likely influenced from work presented at the 1913 New York Armory show. The Armory exhibition first introduced European Modernism to US audiences.

Stuart Davis visited Paris during the Depression-era. Imagine him mingling with the Avant Garde artists who for the first time freely abstracted elements of a still life or a portrait, playfully challenging spatial relationships. And importantly, Davis experienced the raw energy of jazz music. The jazz genre was perhaps the most important influence on Davis’ interpretation of the world around him; a parallel aesthetic that he translated into his paintings. Riffs and improvisation solos are the main hallmark of jazz music; often unrehearsed or not scored… a spontaneous, emotional, solo expression by the musician.

As Davis’ art matures, his contemporary signature is not unlike that of a musical painter. And like the Cubist Avant Garde artists, Davis abstracted his themes; painting a record of the everyday scenes and experiences around him.

Jazz is a musical journey, a metaphor for the visual journey that lies beyond the train tracks in Yellow Hills.

In his journal, Stuart Davis mused that: “Art has nothing to do with Logic or Sensibility. It has to do with Intuitive impulse carried out as an Act. The Act is the Fact, and all the Art quality is in it”.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

After his epiphany at the 1913 Armory exhibition, where Davis saw works by Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Matisse, he wrote the following: “I resolved that I definitely had to become a “modern artist.” It took an awful long time. I soon came to look at color more objectively so that I could paint a green tree red without batting an eye … but the ability to think about positional relationships objectively in terms of what they were, instead of what they represented, took many years.” While Davis’s technique would continue to morph over the course of his career, this painting is an excellent example of the lessons he gleaned from Van Gogh as applied to the Pennsylvania landscape. Paint is so thickly laid on that the impasto casts shadows and the high color palette responds less to descriptive ends than to the artist’s emotional response to the motif. Clearly, the darker palette and urban realism of the Ashcan School to which he had earlier subscribed no longer held sway. Davis would go on to take a leadership role in American modernism, developing his own deadpan version of Cubist-inspired abstraction, often impelled by the design aesthetics of collage.

- Highlights of American Art, 2020