Arthur B. Davies

American, 1862-1928

Redwoods, 1905-1913 ca.

oil on paper mounted on board

18 x 40 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase

1967.6

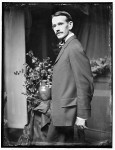

Photo by Gertrude Kaesebier, 1907.

RESEARCH PAPER

Art historians writing in the 1950s and 60s have little to say about Arthur B. Davies’ paintings, but they assign him an influential place in the history of American painting. Because he was a highly respected artist and receptive to new ideas, he was a cataclysmic agent in the movement which generated modernism in American painting. He was one of the first American painters to recognize the meaning of what was taking place among his European contemporaries—Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian. Davies and several other artists, known as “The Eight of 1908,” defended the right of an artist to express his perceptions in innovative ways.

Though Davies’ paintings were very unlike the paintings of the other seven who exhibited in a revolutionary show in the Macbeth Gallery in 1908, his insistence on a highly individualistic approach to painting made him an important part of the group—later derisively called the “Ash Can” school of painting because of its portrayal of the raw, grittier scenes in American life.

In 1913, Davies was the director of the famous Armory show in New York, an exhibition that gave cubists and so called “modernists” their first comprehensive show in America. The Armory show appears to have been to modern American art what the Salon des Refuses was to the French Impressionists—the event that shocked the public into recognition of a shockingly new and different way of looking at the world.

Davies did experiment with Cubism after the exhibition, but the works were not considered successful by himself or the critics. He returned to a type of painting similar to the style demonstrated in the “Redwoods.”

The painting depicts groups of nudes and semi-nudes against a landscape of massive redwood trunks. It appears that one of the “tribe” has met a fatal accident, judging by the pallor of the body and the gestures of abandoned anguish of some of the other figures. The up thrust arms of the figures symmetrically echo the vertical lines of the trees.

Davies was greatly impressed by the work of Cezanne. In “Redwoods” one can see the architectonic influence in the build up of rhythm and the forward push toward the surface of the canvas. We feel the mass and weight of the tree trunks much more than we would whole trees. There is a somewhat modern push-pull effect—our eye travels in and out, from foreground to middle ground to background through the use of line and color zones, though the foreground demands most of our attention.

There is symmetrical balance to the painting in terms of mass—a central pairing of two large trunks with figures grouped against them, with peripheral figures inclined toward the center or side. This might be construed as a romanticizing of the relationship between man and nature. The figures do not appear to belong to any specific race. Though the figures are well drawn, there is a vagueness and impersonality about them, as if they are part of a design, generalized human beings, stripped of the identity of time and culture, placed in a timeless forest.

Though the painting is not considered a revolutionary work of art, it is reflective of the changes taking place in American painting.

J.C. (from the SBMA Docent Files n.d.)

Typed for the docent website by Teda Pilcher and edited by Lori Mohr, fall 2012.