Salvador Dalí

Spanish , 1904-1989 (active France, USA)

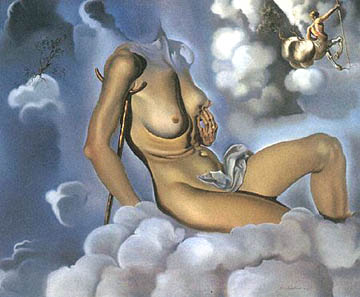

Honey is Sweeter than Blood, 1941

oil on canvas

20 x 24 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Warren Tremaine

1949.17

Salvador Dali - Detail from "The Ecumenical Council", 1960, Oil on canvas

RESEARCH PAPER

Salvador Dalí brought his own unique vision to 20th century art. Known for his flamboyant, arrogant behavior, he was a self-promoter and an eccentric exhibitionist, overt in his obsession for making money. He nevertheless created a body of work that is easily recognizable and continues to be studied and scrutinized by art patrons and scholars alike.

Dalí, the son of a respected notary, was born in Figueres, Spain in 1904. His mother’s Roman Catholicism and his father’s radical political views proved to be major influences on him. Dalí was named Salvador in memory of his deceased older brother, a factor that may have contributed to his frequent questions about his identity, and fueled his insecurities and fertile imagination. The Dalí family spent summer vacations on the Catalonian coast in the town of Cadaques. The beauty and emotional connection of Catolonia provided an important creative impulse for Dalí throughout his career as an artist. Dalí and his wife eventfully purchased their own cottage in the region.

A family friend and impressionist painter Ramon Pichot (1872-1925) is credited with introducing Dalí to painting. Showing remarkable talent, Dalí was admitted to the San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts in 1922 only to be expelled before graduation for inciting rebellions among the student body. Dalí continued to paint on his own, exhibiting in a one-man show in Barcelona in 1929. This marked the beginning of his successes but also the continuing controversy about his work throughout his lifetime. During these early years as an artist, Dalí experimented with a variety of painting styles including impressionism, cubism, fauvism and neo-classicism. Ultimately he arrived at his own style displaying superb draftsmanship, “academic precision and photographic realism”. He was strongly drawn to the styles of the Renaissance and classical painting.

It was inevitable that Dalí would be drawn to Surrealism in the 1920s and the ideas of French artists and writers like Rene Magritte, Jean Arp, Max Ernst and Andre Beton. Influenced by the writings of Sigmund Freud whose ideas of sexual repression were manifested in dreams and delusions, the surrealist artist attempted to re-create these dreams in paint. Dalí moved beyond merely trying to capture the subconscious. His genius lay in examining objects from several perspectives, to look at things differently. This ultimately let him to develop his self-described “paranoiac-critical method”—the ability to focus like a paranoiac who misreads the ordinary and becomes liberated from conventional thought patterns. This methodology helps explain the double images and dualities in Dalí’s work. In 1939, Andre Beton, the leader and founder of the Surrealist movement, officially expelled Dalí. He took issue with Dalí’s political views and unabashed commercialism.

For the remainder of his career Dalí was no longer officially associated with any specific “art movement”. He moved to the United States with his wife for a self-imposed exile during World War II. It was shortly after his arrival that he painted SBMA’s painting “Honey is Sweeter than Blood” at the tranquil estate of art patroness Caresse Crosby in Virginia.

“Honey is Sweeter than Blood” confronts us with the enigmatic character and visual surprise of the subject, along with meticulous old master like technique. The central focus of the painting is a female nude, her faceless head dissolving into the sky. She floats on a bed of mythological clouds. A skeletal hand pierces her left breast, while the right hand falls beneath the clouds. She supports herself on a crutch. In the upper right hand corner of the painting, a blond haired centaur (half man, half horse), his back to the viewer, rides away into a sea of darkening clouds. He too has a crutch in hand, and olive branches growing out of his enlarged haunches. The olive branch motif is repeated on the left side of the painting atop of cloud formations. The colors are somber; the sky, varying tones of bluish gray; the figure, ashen skinned and sculpted with deep shadows and light.

What is Dalí’s message? There are multiple interpretations including the erotic, allegorical, and allusions to his personal mythologies as expressed in his personal writings and his acclaimed autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dali. Dalí forces us to look at things in more than one-way.

Dalí was distressed and deeply affected by the war and the continuing German conquest of Europe following on the heels of the Spanish Civil War. This picture reflects his angst. The ravished female (Europe) attempts equilibrium and stability by leaning on her crutch as the “Aryan” centaur departs the scene for further conquests. In classical literature, the centaur symbolized animal passion and rebelliousness. Note the haunches of the centaur. They appear to replicate the male genitals; the same shapes are repeated in the cloud formations.

Clouds have a metamorphic quality. They can denote ecstasy but can also reflect the Italian Baroque with its mythological/religious figures floating in them. The crutch in this picture is a recurring visual image in Dalí’s work. The crutch offers support, both imaginative and real. It shores up decaying social and political structures. It serves as a weapon, a protection, and can be a tool of sexual fantasy.

The olive branches offer multiple interpretations as well. They are a traditional peace symbol. They represent the trees indigenous to Dalí’s beloved Catalonia. The mythological centaur used the olive branch as a weapon. The Roman Catholic Church used olive oil for sacramental ceremonies and “suggests the transubstantiation of the body into the spirit.” Dalí also used the olive branch as a symbol of his wife “Gala”, his muse to whom he attributed his salvation and stability.

The painting’s title is a juxtaposition. Blood in the Spanish culture infers passion, virility, and the familial. Honey is the symbol for the sweetness of the female sex; truth as opposed to violence. Dalí made erotic references to masturbation being…” sweeter than honey”… Note the offering of the breast as honey even if held by a desecrated hand. The nude figure conjures up multiple interpretations including questions of the ugly versus the beautiful; pleasure versus terror. Are we witnessing the classical idea of poetic death after sex?

This painting is signed Gala Salvador Dalí, a custom Dalí adopted in the 1930’s. He attributed his success to his wife Gala who supplied his life with organization, peacefulness and stability.

“Honey is Sweeter than Blood is important as a document to be fathomed in terms of the crisis, both individual and historical, moral and aesthetic in the career of Dalí as an artist…it has much to say about our 20th century era…The contradictions of values, the romantic nostalgia for a saner, less confused and freer time and the aspiration to create something unique and immortal out of the dross of sullied human existence—these components of Dalí’s aspiration all reverberate out of this technically “crystalline”, yet thematically complex and puzzling picture. Its theme and technique reveal Dalí…as an imaginative humanist and superb craftsman with an appropriate respect for traditional western values in a period of dark despair for western Europe.” (1)

The provenance for this painting is short. After being shown in 1941 at the Julian Levy Gallery in New York City, it next appeared in 1945 at the first exhibit of Dalí’s work on the west coast in Los Angeles at the Dalzell, Hatfield Galleries. Purchased by the Hatfields directly from Dalí, it was re-sold to The Warren Tremaines of Santa Barbara in the same year.

After the war Dalí continued to be a prolific painter. His work reflects an increasing interest in science, atomic technology, and religious themes. He died in 1989 leaving a legacy not only in painting, but a profound influence on modern drama, films, advertising, furniture and jewelry design, architecture and literature. Two museums, one in St. Petersburg, Florida and one in his hometown of Figueres, Spain are exclusively dedicated to the preservation of the Dalí heritage.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Susan Northrop 2006

Footnote

(1) p.185 Archivero I

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Archivero I, Research Papers on Works of Art in the Collection of The Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, Ca.1973.” Honey is Sweeter than Blood”, Ronald Kuchta

Ades, Dawn and Bradley, Fiona, Salavador Dalí, A Mythology, Tate Gallary, Liverpool, October 24, 1998- January 31, 1999.

Lubar, Robert S., introduction, Dalí, The Salvador Dali Collection, The Salvador Dali Foundation, Inc., A Bulfinch Press Book, Little Brown and Company, 1991

Dalí, Philadelphia Museum of Art Catalog, 2005, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, Italy

The Dictionary of Art, Jane Turner, ed. NY, Macmillan, 1998

Periodicals:

Surrealism USA

“Salvador Dalí in America: The Rise and Fall of an Arch Surrealist”, Robert S. Lubar, National Academy Museum, NY, 2005

Art in America, “The Persistence of Dalí”, Charles Stuckey, March 2005

Smithsonian, “The Surreal World of Salvador Dalí”, April 2005