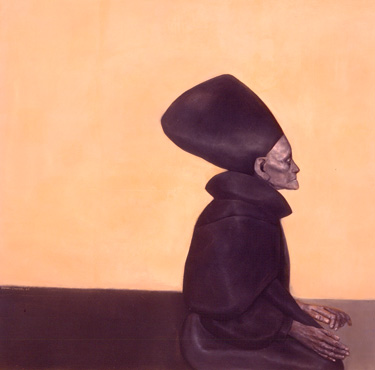

Rafael Coronel

Mexican, 1932-

Rosa en el pasillo, 1967

oil on canvas

47 1/2 x 47 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of an Anonymous Donor

1997.74

Undated photo of Coronel

RESEARCH PAPER

Gerzso was maybe the best representative of the abstract movement, a reaction against what had become an institutionalized nationalistic tradition in Mexican art. In turn, Rafael Coronel (17 years younger than Gerszo), with some of his young contemporaries, reacted against abstraction and led a return to figuration and people as their main subject.

We know that this is one of three portraits that Coronel made of his grandmother, although he does not tell us who Rosa is. In fact many of his paintings are untitled or bear a title, which is a mere description of their subject (e.g.: "a young man with a hat".) The artist is a man of few words [Slide: self portrait] but a sympathetic depicter of the human chronicle he also called "the Carnival of life".

First, a shock in front of this smooth, luminescent apricot, light terra cotta color of the wall which becomes a halo for Rosa, in contrast with her black silhouette, with her mysterious, elongated black hat, the dark smoky color of her face and hands, with the black of the ground behind her as well as the light grey of the ground in front of her. Then there is Rosa's chiseled solitary profile looking straightforward. What is she seeing, expecting?

Look at her wrinkled, emaciated face, her stern, but somewhat apprehensive gaze. This face is almost a mask with its deep, sharp lines. The lower line of the hat emphasizes the long, determined chin. Her hands now at rest, encrusted with indelible black lines, with their broken nails, are worn by domestic tasks. In this respect we have a very realistic rendition of an old woman who has known a very harsh life. Her posture is very evocative of all this: she is kneeling, a posture of care and acceptance, if not submission. But, strangely enough, although she is the only subject of this picture she is placed off center, to the right. The stretch of black behind her is much longer than the grey path ahead of her. She is reaching the end of the corridor, as indicated y the closeness of the frame. Space has become time. She is awaiting death, alone. This concern with the passage of time and impending death is very much one of Coronel's preoccupations as shown by this later work titled "Time."

It is also that of many Mexican writers and artists in the sixties who were influenced by the ideas of the French existentialist philosophers and shared their sense of alienation, of solitude, and the absurd in the human condition. Furthermore death has been and still is at the core of Mexican popular culture.

But surely, this old grandmother did not dress this way. What about this huge hat and ample medieval cloak? Here we abandon descriptive realism. Imagination takes over. The medieval cloak imparts this humble woman with mystery, timelessness and magic powers. The hat is especially puzzling, because it is reminiscent of various past representations:

-- Nefertiti, the young Pharaoh's spouse, thus elevating Rosa to the rank of a queen. She becomes a distant descendant.

-- some have mentioned the Pope's tiara: Catholicism is deeply rooted in Mexico and Rosa in a way has become a priestess, the priestess of the household, a symbol of the holiness of simple dedicated people. This vision is completed by the beautiful luminescent halo surrounding her.

-- She is also reminiscent of the profile of the Mayan priests as represented on the bas-reliefs in the ruins of Palenque.

In fact, Rosa may be all of the above since in the 70's Coronel has become preoccupied with the representation of people as inheritors of the past. And a grandmother is an intimate link with the past. Time implies history and timelessness.

In the portrait of Rosa Coronel's style contributes greatly to the expression of all the ideas and feelings I have just tried to evoke. On one hand we have what a critic called "the modernist emphasis on the radical bi-dimension of painting": the large flat smooth areas. On the other hand the rendering of the face and the hands are as detailed as were 17th and 18th c. Dutch portraits.

But who is Rosa's grandson, the elusive Rafael Coronel? A shy man with a sense of humor and a strong dislike for interviews, critics, and labels, but who enjoyed the company of a few close friends. A man with an incredible talent for drawing, as well as for colors, a "geyser" as he was referred to in a rare interview given in 2000, for a retrospective of his life’s work in Mexico City. He is indeed a very prolific artist, who became famous at the age of 21.

Born in 1932 in a family of artists and collectors -- his older brother Pedro Coronel is also a sculptor and a painter. Both are avid collectors and have created two national museums to house their collections in Zacatecas, the city where they grew up. Rafael's museum contains what he calls "his junk”: a collection of 5000 traditional masks! The mask-like profile of Rosa's face is not purely coincidental. For Coronel, masks are powerful, allow people to become someone else, to hide and to express themselves fully and anonymously. This passion for masks also reflects his deep preoccupation with history, tradition but also the difficulty of communicating, and the loneliness of the individual.

In the 50's, Coronel expressed suffering and human loneliness with distorted and distressing faces. But around 1960 he flirted briefly with the movement called "Nueva Presencia" (the new presence), and maybe under the influence of the future members of the "interioristas", the Insiders -- a bad translation, he decided to put a distance between him and his subject, thus showing respect for their humanity.

Wrapping them in a halo, and mysterious clothing was a way of elevating the most humble to greater dignity. "The Interioristas" whom I would rather call" the Interiorists" campaigned for art to re-center on the representation of people, especially the downtrodden, the maimed, the dispossessed. He also represented a few animals, also a symbol of poverty and the rundown conditions of urban life. Here the halo is inverted!

In 1961, Rafael Coronel went to Europe for the first time and from then on he will turn himself towards the past. The Baroque artists, especially Caravaggio, then Rembrandt and Goya will have a very strong impact. He also mentions Piero della Francesca and above all Ucello. He said that he feels a thousand years old when he paints and that he sees himself as a painter of the XIXth c... which may explain why contemporary critics are not very interested in him.

I would like to conclude with Coronel 's rendering of a man who fascinated him, probably because he may have been the supreme expression of the condition of the little man. Nevertheless Coronel is a man of the XXIst century and is much more disillusioned than Chaplin was: Hope is never there in his representation of the disinherited!

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Jacqueline Simons

POSTSCRIPT

Museo Rafael Coronel

The wonderful Museo Rafael Coronel in Zacatecas, Mexico occupies the ex-Convento de San Francisco on the north side of town. Founded in 1593 as a Franciscan mission (the facade is said to be the oldest in the city), it was rebuilt in the seventeenth century, only to begin deteriorating after the Franciscans were expelled in 1857 and finally suffer destruction during Villa's assault. The building and gardens have now been partially but beautifully restored, and the museum brilliantly integrated with the ruins. There are more than four thousand masks on display, which makes taking it all in a bit overwhelming. The masks trace the art's development in what is now Mexico from some very ancient, pre-Columbian examples to contemporary masks: often there are twenty or more variations on the same theme, and one little room is entirely full of the visages of Moors and Christians from the Danza de los Moros y Cristianos. As well as the masks, you can see Coronel's impressive collections of ceramics and puppets, the town's original charter granted by Philip II in 1593 and sketches and drawings connected with Coronel's wife Ruth Rivera, architect and daughter of Diego.

www.roughguides.com/travel/north-america/mexico/the-bajio/zacatecas/museo-rafael-coronel.aspx

LG 2012

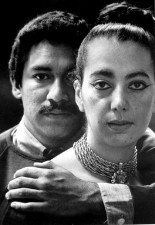

Rafael Coronel and Ruth Rivera, 1964. Photograph by John Bryson

COMMENTS

Rosa en el pasillo portrays Rafael Coronel’s grandmother and suggests the passage of time. Rosa’s chiseled and weathered face evokes a lifetime of experience and wisdom. The stillness of the sparse setting is matched by the old woman’s stoic, mask-like expression. Her relaxed pose imparts a sense of quiet solitude as she awaits death.

A concern with the transience of life has preoccupied Coronel throughout his career, and is apparent in the way he represents people as inheritors of the past. Most strikingly, Rosa’s black cloak and towering hat imbues the humble woman with a sense of mystery and mysticism. Her costume and stark profile may make reference to Nefertiti, the Pope in regalia, and the bas-relief carvings of priests at the Maya ruins of Palenque.

SBMA title card information 2013

Rafael Coronel is the younger brother of artist Pedro Coronel. He is also the son-in-law of Diego Rivera. In 1959 Coronel meets Ruth Rivera, daughter of Diego Rivera (1886-1957), whom he married in 1960.

Rafael Coronel well represents the Ruptura (Rupture) movement in Mexico, also known as Nueva Presencia (New Presence) after a broadsheet of that title that was issued in 1961-63. The movement consisted of a shift away from heroic Muralism toward a more traditional way of art making. Coronel and others created easel paintings for a professional class that lacked the forceful social statements of the Muralists' works. Coronel's paintings are ambiguous and suggest that man's efforts to control his destiny are futile. His paintings of old men and women, isolated and floating in nebulous space, suggest a return to the Old Master tradition, especially Goya and Spanish painting of the seventeenth century. His first solo exhibition occurred in 1956, and he painted two murals at the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City in 1964.

http://www.latinart.com/faview.cfm?id=123

LG 2010