Bruce Conner

American, 1933-2008

Plate IV from The Dennis Hopper One Man Show, Vol. II, 1972

photo-etching

9 1⁄4 x 9 1⁄2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Betty and Bob Klausner to the Contemporary Graphics Center, William Dole Fund Collection

1983.68.5

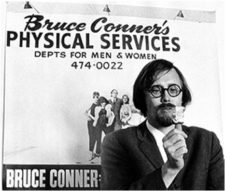

Undated photo of Conner and ABOVE Dennis Hopper and Bruce Conner swap directors chairs at San Fransisco opening, 1973

"I am an artist, an anti-artist, no shrinking ego, modest, a feminist, a profound misogynist, a romantic, a realist, a surrealist, a funk artist, conceptual artist, minimalist, postmodernist, beatnik, hippie, punk, subtle, confrontational, believable, paranoiac, courteous, difficult, forthright, impossible to work with, accessible, obscure, precise, calm, contrary, elusive, spiritual, profane, a Renaissance man of contemporary art, and one the most important artists in the world. My work is described as beautiful, horrible, hogwash, genius, maundering, precise, quaint, avant-garde, historical, hackneyed, masterful, trivial, intense, mystical, virtuosic, bewildering, absorbing, concise, absurd, amusing, innovative, nostalgic, contemporary, iconoclastic, sophisticated, trash, masterpieces, etc. It’s All True." - Bruce Conner

-It’s All True — was derived from a letter that the artist wrote to his friend and collaborator, Paula Kirkeby, in 2000, listing the many ways he had been characterized in the media.

POSTSCRIPT

Defying strict classification and transcending the limitations of any single genre, multimedia artist Bruce Conner will be celebrated in an extensive retrospective at SFMOMA October 29, 2016 – January 22, 2017 after its initial iteration at MOMA NY. Referencing the artist’s inimitable and ever-changing methods, the subtitle of the exhibition — It’s All True — was derived from a letter that the artist wrote to his friend and collaborator, Paula Kirkeby, in 2000, listing the many ways he had been characterized in the media.

Conner, who died in 2008 after having lived in the Bay Area for more than fifty years, is not only a seminal figure regionally, but also nationally and beyond. His avant-garde film work remains a touchstone in the international film scene, as well as across a spectrum of contemporary art. The exhibition at SFMOMA will be the most comprehensive view of Conner’s work to date and will include more than 300 works from all media.

From his early assemblages in the 1950s and 60s to his iconic and pioneering work with the language of film, from his photography and photograms to his prints, drawings and paintings — the sheer diversity of works created during the course of Conner’s career is astounding. With Bruce Conner: It’s All True, SFMOMA pays homage to this exceptional Bay Area artist and places him in an international context, marking the tremendous influence he has had on generations of artists, and continues to exert today.

-sfmoma.org

COMMENTS

Bruce Conner’s Darkness That Defies Authority

By ROBERTA SMITH

JUNE 30, 2016

Bruce Conner was one of the great outliers of American art, a polymathic nonconformist whose secret mantra might have been “Only resist.” In multiple media, over more than five decades, this restless denizen of the San Francisco cultural scene resisted categorization, art world expectations and almost any kind of authority.

His opposition took the form of dark assemblages made from the detritus of modern life that include some of the most forceful evocations of American violence in 20th-century art, and often ecstatic black-and-white films that protest the world’s destructive powers. He was a master of Conceptual Art pranks that questioned his own authorship, and an ardently unreconstructed admirer of nude female beauty. Yet he also liberated his art from time and place with ink drawings whose eddying patterns and shadowy mandalas — created by minute dots — could be the work of Tibetan Buddhists forsaking sand painting for paper.

Conner, who was born in Kansas in 1933 and died in San Francisco in 2008, belongs to American art’s genius-heavy postwar generation, born mostly between 1925 and 1937: Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Ed Ruscha, Eva Hesse, Andy Warhol and Edward Kienholz. Like many of those artists, Conner was shaped by the clash between the intense emotionality of Abstract Expressionism and the sardonic worldliness of Dada. Conner gathered his knowledge of these tendencies from the art magazines he pored over in high school in Wichita, Kan., and the visits made to New York during his student years at the University of Nebraska. Graduating in 1955, he won a six-month scholarship to study painting at the Brooklyn Museum’s art school. His first solo gallery show took place in New York in 1956.

But Conner, politically minded from the start, set his sights on San Francisco, where he rightly decided that the art world’s machinations would be less oppressive. He moved west in 1957, just after he and Jean Sandstedt, an artist he’d met in college, married; they were preceded by one of his closest high school friends, the poet Michael McClure. There Conner joined the counterculture, and fearlessly evolved into one of America’s first thoroughly multidisciplinary artists.

Conner was a blessedly orderly one for an artist who habitually worked on several fronts at once. His different mediums are isolated in separate areas, with the films sprinkled throughout.

BRUCE CONNER

DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW, 1971-73. In their final state, the twenty-six images that comprise the series were bound into three leather volumes.

The genesis for this print project dates back to the late 1950s, when Conner began a series of paper collages using fragments of 19th-century engraved illustrations styled on those by French Surrealist Max Ernst. Conner’s collages depict a surreal, hallucinatory universe populated by images of flora and fauna, machine parts, and disembodied figures. His use of disparate appropriated and recycled materials parallel the techniques used to make the films and assemblages for which he is well known. Interested in shifting personas and subverting traditional notions of authorship, Conner attributed this body of work to his friend and fellow Kansas native, Dennis Hopper. The unwillingness in the mid-1960s of his Los Angeles dealer Nicholas Wilder to exhibit the work under another’s name, as well as Conner’s refusal to reveal his own identity, led to their relative obscurity during this time period.

A decade later, these collages became the source material for a series of photo etchings produced with Kathan Brown at Crown Point Press in Oakland, CA and published in 1971-73. In a performative full-circle, Conner returned the collages to their original printed state, producing twenty-six etchings bound in three black leather volumes and titled collectively DENNIS HOPPER ONE MAN SHOW VOLUMES I–III. Conner printed a limited number of unbound etchings. Acting simultaneously as artwork and as foil for a larger conceptual project, this series is considered by many to be among Conner’s major works.