Willie Cole talks about his work Man, Spirit, Mask (video 4:08)

Willie Cole

American, 1955-

Man, Spirit, Mask, 1999

triptych: photo etching; silkscreen; photo etching with woodcut

39 1/8 × 79 1/2 in.

SBMA, Museum Purchase, General Art Acquisition Fund

2020.16a-c

Willie Cole, Self Portrait, ca. 1977

“My relationship with [the steam iron] began in 1988 when I spotted one on the street near my Newark studio, all flattened and discarded…. Right away I saw it as an African mask, more specifically a Dan mask...I brought it into my studio, photographed it, and made a list of all the things it suggested to me.” - Willie Cole

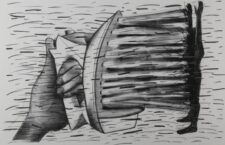

Willie Cole, Steamed Man, Lithograph, 2077. The Fort Wayne Museum of Art

COMMENTS

Everyday objects, such as steam irons and ironing boards, act as both the subject and the material in Cole’s art. There, these household goods have a range of associations including slave ships, African art, domestic labor, and the found objects of the Dada and Surrealist art movements. In Man, the left panel, a manipulated, black-and-white photograph of Cole’s face is overlaid with the embossed outline and scarification-like markings of a steam iron. In Spirit (center), an iron’s base is rendered in brown tones and with blurred edges, referencing a scorched surface as well as the markings on Cole’s photograph of his face. At right, a bird’s-eye view of an antique dry iron with a wooden handle resembles an African mask placed over an upside-down version of Cole’s portrait.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/383685

The last time Willie Cole's work was out on view, a high school student walked in and stood transfixed in front of Mon Spirit Mask. He whispered, “Wakanda". The creators of the movie Block Panther used motifs and forms from different African cultures in their depiction of the fictional Wakanda. Likewise, the artist Willie Cole references African rituals and sculpture in his works to add layers of meaning. I loved how this movie and artwork could make such a personal connection for him.

A perceptual engineer is what Cole prefers to call himself because he likes to challenge us to see everyday things in new ways. A father of two, he enjoys mentioning that his son always watched Transformers and played with the toys, which Cole found inspiring. He in turn transforms discarded objects into sculptures, drawings, and prints. Some might compare Cole to artists, such as Robert Rauschenberg and Arman, who used throwaway objects from consumer culture. Dada artist Man Ray's Gift (I921), an iron with tacks, also comes to mind as a predecessor. Cast off materials were readily available, but Cole focuses on only a select few objects that speak to him. In his hands irons, blow dryers, high-heeled shoes, and plastic water bottles change into anthropomorphic forms making associations with African culture, domestic labor, and religious ritual.

One of his favorite go-to objects from his personal iconography is the steam iron. Ironically, Cole lived in Iron Bound, a Newark neighborhood where he had his first studio. Previously, this studio space was a sweatshop where a lot of ironing was done, and ironing boards were abandoned and left there. Irons have a rich cultural history and relate to the Cole's own personal heritage. His great grandmother and grandmother were domestics, a role commonly assigned to women of color in American society as maids, nannies, or house slaves.

The steam iron features prominently in Man, Spirit, Mask, which consists of three individual parts to create a triptych. The first image, man, uses the artist's face with distinctive embossing, recalling African ritual marking or scarification. After closer

examination, we realize that the markings form a pattern of steam-holes and slits from the underside of a household iron. The steam-hole patterns are unique to a brand, whether it be Proctor Silex, Sunbeam, or General Electric. Cole likens them to different tribes.

The second image resembles a large-scale scorched marking from an iron, the spirit of his object. The imprint’s outline is indistinct and fiery. In other examples of his scorches, Cole repeats the form to build different shapes or decorative patterns,

not unlike Adinkra cloth from Ghana. The third image is abstract reminiscent of a tribal mask or shield, but we see that it is a view of an iron with the handle side up. It is the way that the spirit is contained or the means of being possessed by the spirit.

Scorching and marking may bring to mind the branding of African slaves. Cole's work also relates to West African spiritual beliefs; Ogun is the powerful god of iron and war among the Yoruba tribe. Imposing an African god upon a Western image hearkens back to African slaves who secretly worshiped their traditional gods in the form of Christian saints in the New World. The iron possesses abstract and functional qualities which, paired with the minimalist form, are linked to the functional aspect and simplicity of design of many African sculptures.

Cole received his bachelor's degree from The School of Visual Arts, New York, in 1976 and was the subject of numerous solo exhibitions, including those at the Museum of Modern Art, the Newark Museum, and the St. Louis Art Museum. He was the artist-in-residence at the Capp Street Project, The Contemporary in Baltimore, and the Pilchuck Glass School and has received awards and grants from the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation and the Joan Mitchell Foundation. His works are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art; Whitney Museum of American Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; National Gallery of Art; Saint Louis Art Museum; Philadelphia Museum of Art; and the Walker Art Center.

- K. Thompson, Treasures from the Vault: Willie Cole, The Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Oct 28, 2019