John Chervinsky

American, 1961-

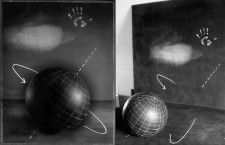

All Watched Over, 2006

archival pigment print

18 x 23 in.

SBMA, Gift of FOCUS in honor of Lisa Volpe

2013.56

Self-portrait, 2013, courtesy of the artist

RESEARCH PAPER

John Chervinsky is a physics researcher at Harvard's Rowland Institute for Science, originally founded by Edwin H. Land of Polaroid. In his time off, he is a self-taught photographer specializing in large-format photographs of composed still-lifes.

As a scientist, Chervinsky is well-versed in the visual languages of scientific notation and diagrams. Working at Harvard, he has had much opportunity to observe slate blackboards in old lecture halls and developed an admiration for the equations, diagrams and half-erasures. These inspired the institutional learning motif notable in “All Watched Over”. The artist applies these visual tools to prompt an exploration of the more ambiguous realms of human emotion. The images in the series are not intended to have scientific content, but rather to symbolize philosophical debates. Rather than offering a culminating moral of the series, Chervinsky aims to create enigmatic images that raise questions about our assumptions and express an open-ended concern about narrow perspectives. Arrows, dotted lines, pulleys, and other notations unique to each work in the series create diagrams to help the viewer decipher the emotional meaning of the image.

In “An Experiment in Perspective,” “perspective” is meant both literally and figuratively. The series was started in 2001, when his personal life was troubled by three tragedies. His wife became seriously ill, a friend suddenly died, and the country was shaken by the events of September 11, 2001. Chervinsky retreated to his attic studio, where he began creating still-life photographs that “attempt[ed] to find metaphors within the laws of nature that can be universally applied to everyday life. Conceptually the work deals with the divide between rational or scientific explanations of existence and man's need to explain the world around him with various systems of belief.” (Artist's Statement, 2011). By executing the images in a science-inspired visual vocabulary, the positivism of Western science is also tacitly addressed as one of many systems of belief used to make sense of life. In this way, the series intends to restore a relativism and graceful uncertainty to the human tendency to become absolutist in our beliefs and approaches to the world.

To make this point, Chervinsky cleverly manipulates depth through a unique still-life process. He creates a set using two blackboards positioned at a 90-degree angle and draws on them with white chalk. He then arranges a still-life in that space and points a large-format view camera at the intersection of the blackboards. As Chervinsky explains in an interview on the Los Angeles Times Framework blog, “The chalk lines were created by taping marked transparency film into the inside of the ground glass of my view camera. That allowed me to shine a light right through it and operate the camera as a projector. I could then trace the lines with chalk around and over the 'corner' of my blackboards. If the illusion was successful, the lines appeared to be floating in space, but only from the vantage point of the camera. Once the lines were drawn, I added objects and used the same camera in the traditional way to capture the final image.” The rich printing of his photographs is often remarked upon, assisting in the impression that the chalk lines are hovering over the scene.

His work may be contextualized in a history of art that challenges illusion, a consideration Chervinsky prompts by using both perspective-based illusion itself, and metaphorically through the titles of his pieces, which are often word-plays helping the viewer uncover meaning. In “All Watched Over,” the reflective orbs and chalk drawings recall a planetary model and are set atop a chess board, suggesting a plan in which inhabitants of these “planets” are “all watched over” in a cosmic order. At the same time, the reflections, which are reminiscent of Dutch artist M.C. Escher’s 1935 “Hand with Reflecting Sphere”, indicate an omniscient surveillance of the room in which the photos were taken, offering a less comforting reading of the title. The sparing use of objects in this piece contributes to a sense of ambiguity or mystery, leaving the narrative or moral of the photograph unresolved and aestheticizing tensions between observation and faith.

Chervinsky's work challenges us to contemplate our own assumptions through images whose interpretations rely on the point of view of the camera; one step in any direction would misalign the composition. The artist's concerns with space and perception are maintained in his second series, “Studio Physics,” which adds multiple references to the passage of time to his construction of still-lifes. Boldly working at the intersection of professional science and art, John Chervinsky's work culminates in an elegant and intelligent look at perception.

As Chervinsky continues his career in physics research, both of his photographic series have been exhibited nationally. His work is held in several institutional and private collections. He is represented by multiple commercial galleries, including Wall Space Gallery in Santa Barbara.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Stephanie Amon, January 2014

Bibliography

http://www.chervinsky.org

“Success Stories: John Chervinsky” on LENSCRATCH: Fine Are Photography Daily, 6/7/11 http://lenscratch.com/2011/06/success-stories-john-chervinsky/

“reFramed: In Conversation with John Chervinsky” on LA Times Framework blog, 10/4/13

http://framework.latimes.com/2013/10/04/reframed-in-conversation-with-john-chervinsky/#/0

The Making of Hope, 2004, courtesy of the artist

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Chervinsky constructs a planetary scene atop a chessboard; he casts away a pawn, and instead “plays” with perspectives. A laboratory engineer at the Harvard University’s Rowland Institute of Science, Chervinsky’s work illuminates the intersection of art

and science. In an effort to explain the importance of physics to laymen Chervinsky draws on blackboards and places them accordingly to explain or reveal concepts of physics. Quite literal in his scientific approach, he poetically employs optics to imply

human presence in relation to science, the universe, and the photograph. The mirrored planets reveal interior views of the photographer’s studio, yet the photographer is still not visible. As perspectives must be contemplated, human presence is merely implied. Such is the relationship between physics and the universe, scientific theories and concepts that persist with or without human life. We may try to understand but they subsist outside of our vision.

- Heavenly Bodies, 2014