William Merritt Chase

American, 1849-1916

Lydia Field Emmet, 1900

oil on canvas

24 x 20”

Bequest of Margaret Mallory

1998.50.23

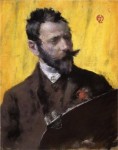

William Merritt Chase, Self Portrait, 1883

“Association with my pupils has kept me young in my work. Criticism of their work has kept my own point of view clear.“

William Merritt Chase

RESEARCH PAPER

THE ART

Lydia Field Emmet was a student of William Merritt Chase, both at the Art Students League in New York as well as his summer school in Shinnecock Hills, Long Island. Chase frequently used his students as models. He shows this young artist as a strong, forthright and capable woman with a definite personality. This manner of presentation is what separates Chase’s work from other portraitists of the period, for instance, the idealized ethereal women painted by Thomas Dewing and the dreamy, melancholy women predominant in Eakin’s portraits. Whistler’s models are more withdrawn and internally focused than those of Chase, and unlike Sargent’s model, not about class, status, imperiousness, and seduction.

Chase uses a limited, subdued color palette, an analogous harmony of toned blues and greens accented with his characteristic brilliant color note. The pink lips and the slight blush on her cheek reveal his ability to enliven a composition with just the right accent. The mood is sober. The brushwork in the background is carefully controlled, yet suggestive of an extraordinarily vibrant and alive space. The face is delicately modeled and bathed in soft, luminous light in dramatic chiaroscuro effect. The texture of lustrous velvet and iridescent silk taffeta of the model’s gown is realized in the most general manner, a mere suggestion; with the lace detail around the neck rendered with a quick impasto brushstroke. Chase uses a frontal, frame-filling composition which places Lydia in the foreground of the painting; it is not clear what she is doing, but her pose suggests that she may be painting out-of-doors, her hat shading her eyes from the glare, right arm extended toward her canvas as she gazes at her subject. Chase’s brilliant use of technique to capture the essence of this beautiful young woman on canvas with such a seeming economy of color, paint and brushstroke truly demonstrates the artist’s genius and his belief in painting only “truth.”

THE SUBJECT

Lydia Field Emmett was born in New Rochelle, New York in 1866. At eighteen she traveled with her sister to Paris to study at the Julien Academy. On her return to New York she worked as an illustrator of books and magazines, experimenting with watercolor, oil landscapes and miniature pastel portraits. She later studied with Chase at the Art Students League in New York and at his Shinnecock Summer Art School in Long Island as well as with Frederick MacMonnies in Paris. She became a successful artist, winning many prizes and awards. Her sense of beauty in children made her especially known for her juvenile portraits. Guy de Bois said, “She is a painter of the American aristocracy, distinct from any other. Her women have intellect, her children health.” One of her paintings is in the SBMA collection; Mrs.Hazard and Her Children, ca. 1922, Chase painted Lydia’s portrait twice, a full length portrait (now in the Brooklyn Museum) and the one in the SBMA collection.

THE ARTIST

William Merritt Chase was born and reared in the mid-west during the time of the Civil War. Indiana-born, his earliest art training as in Indianapolis with portrait painter Barton. S. Hays. In 1869 he went to New York to study at the National Academy of Design. Having run out of funds, he joined his family in St. Louis in 1871, where a group of local businessmen, recognizing Chase’s abilities, raised the money to send him to Europe for further study. In return he was to do a painting for each of them as well as act as an agent to purchase European art.

He entered the Royal Academy in Munich in 1872 where he studied for the next six years. The School emphasized bravura brushwork (a technique that became integral to Chase’s style,) favored a dark palette and encouraged the study of old master painters, particularly Diego Velasquez and Frans Halls. While at the Academy he greatly admired the philosophy and work of Wilheim Leibl. It was Leibl’s belief that in painting subject matter was secondary to technique. This philosophy and his admiration of the old masters were two aspects of Chase’s Munich training that were to remain a fixed part of his art.

Chase returned to New York in 1878, at the time of America’s “Gilded Age,” from which sprang the Aesthetic Movement in America, its museum age, and the age of magnificent public buildings and spaces and the obsession of the upper classes with collecting art. Portrait painting was the primary way artists earned their living in nineteenth century America; the portrait had become a standard feature in upper-class homes.

Upon his arrival in New York Chase enthusiastically seized the opportunity at hand, he acquired the most desirable studio in the city, assumed an important teaching position at the most advanced school, the Art Students League, and became an active and vital spokesman for American art in general.

The 1880’s were for Chase a period of intense activity as well as artistic growth. He continued to teach at the Art Students League and to give private lessons in his studio on the Tenth Street Studio Building, New York’s famous artist’s residence. His own ornately decorated studio, which became a gathering place for artists, students and patrons, was filled with a wealth of objects, his own paintings, those of others, and oriental rugs, tapestries and various other treasures and decorative art objects. Chase’s strength as a painter as well as his flamboyant life style made him a favorite subject of art writers of the time. He socialized with the celebrities of the day, including famous architect Stanford White and writer Henry James. Chase was a brilliant teacher and born communicator, gregarious, clubbable and a virtuoso. He became one of the most fashionable portraitists in New York.

In 1885 Chase met James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Chase was greatly influenced by Whistler’s technique and formal innovations. Following an encounter during a summer with the artist in London and Holland, Chase returned home and began using a more subdued palette, applied his paint more thinly, using atmospheric-like washes. Chase also began to use the name of the color in the title of his paintings to emphasize their aesthetic rather than factual content, thus emulating Whistler who stressed the “art for art’s sake” nature of his images by giving his paintings titles such as “Arrangement in Grey and Black, #1, 1872 (The Artist’s Mother.) Subsequently, the aesthetic influence of Whistler can be seen in a remarkable group of large, full length, female portraits which Chase painted between 1886 and 1895, characterized by a limited subdued palette accented with shots of brilliant color, the simple tonal background, the subtlety of brushstroke and the delicacy of paint application. An example of one of these portraits is in the SBMA collection, “Lady in Pink (Portrait of the Artist’s Wife)” 1886.

Chase was known primarily as a realist, but he had made many trips to Europe, beginning in 1881, which brought him into contact with Belgian painter Alfred Stevens and the work of the French impressionists. Their influence is apparent in the lighter palette of his landscapes and genre paintings. His landscapes after 1890 capture the essence of American impressionism. These plein-air works are brightly colored and emphasize transient atmospheric effects. As he had always painted directly on canvas, the adoption of an impressionist approach was a natural evolution in his art.

Chase worked mainly in oil; however his works in pastels are regarded among the finest ever produced in America. The sensitive and very personal nature of the works makes them especially endearing and the most sought after by collectors and museums today. Although known for his remarkable landscapes, it is his portraits that are responsible for Chase’s initial fame and current cultural esteem. Today the name William Merritt Chase together with Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler is synonymous with a great golden age of portraiture.

In 1886 Chase married Alice Gerson, with whom he had nine children. As his domestic life took on greater importance, Chase’s art evolved. Alice, a beguiling beauty seventeen years his junior, would along with her children become his most important models. Chase was the most popular and influential art teacher of his day, teaching more students than any other artist in this country. It was an important part of his life. He was proud of his profession as a teacher and he took a personal interest in the development and success of each of his students.

Chase encouraged his pupils to work directly from nature and model, stressed technique over subject matter and advocated drawing directly on the canvas with a fully loaded brush, avoiding a preliminary sketch in pencil or charcoal. He encouraged individuality in his teaching, realizing that new ideas and approaches to painting were signs of vitality. As a result his students developed a wide range of artistic statements and diverse styles, and some to Chase’s chagrin, went on to become avant-garde artist. Some of the more well know are Georgia O’Keefe, Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Joseph Stella and Edward Hopper. In his earlier career, Chase was considered a radical, at the forefront of the modern movement associated with the Society of American Artists. However, in his later years he was vocal in his opposition and disapproval of the new modern movement and harsh in his criticism of the major figures associated with this movement. He proposed that if Cubist paintings were hung upside down, could anyone figure out which was up and which down. Of Robert Henri and the Ashcan School he said, “A certain group of painters in New York paint the gruesome, they go to the wretched part of the city and paint the working people. They have the nickname “Depressionists.” His reputation suffered after his death because of this criticism and partly because he was regarded as a defender of old fashioned ways.

William Merritt Chase was a prolific painter of portraits, landscapes and still-lifes, renowned teacher, leader of societies of artists, gifted connoisseur of American and European paintings and a devoted family man. Chase fought the battle for American art, a staunch advocate of American art, credited for the general public gaining faith in their native artists.

PROVENANCE

Lydia Field Emmett, a gift of Margaret Mallory, was part of a large gift of over eighty works of art that Mallory loved best, objects from her Montecito home which held a wonderful eclectic combination of decorative and fine arts. Mallory called herself a collector of “anything that is beautiful”. She followed her own advice to collectors, to respond to form and color regardless of period, medium or importance of the artist and to buy for the sheer pleasure of looking. Mallory was introduced to the work of Chase through her friendship with Ala Story. Margaret Mallory and Ala Story moved to Santa Barbara in 1952 when Story became the Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s second director. In 1948 Ala had organized the first Chase retrospective after the artist’s death in 1916, at the American British Art Center in New York. The following year she helped organize the Chase Centennial Exhibition at the John Herron Art Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana, which stimulated resurgence in the artist’s reputation. In 1965, another major showing, and the first West Coast retrospective of Chase’s work was curated by Ala Story. Mallory particularly admired the portrait of Lydia Field Emmet, one of Chase’s prize students.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Irene Chisholm, March, 2004

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Dictionary of Art – 1998 Volume 6, Grove Dictionaries, Inc. N.Y.N.Y

Chase, William Merritt, Akron Art Museum, exhibit catalog, 1982

William Merritt Chase – Portraits, Georgia Museum of Art with The Irvine Museum

Exhibit catalog, 1996, California Impressionists

Hughes, Robert, American Visions, The Epic History of Art in America, Alfred A. Knoph, Inc. N.Y,N.Y, 1997

Pierce, Patricia Jobe, The Ten, Rumford Press, Concord, N.H., 1976

Pisano, Robert G., A Leading Spirit in American Art: William Merritt Chase 1849-1916, Henry Art Gallery University of Washington, Seattle, 1983

Rosenblum, Robert, 1900, Art at the Crossroads, Harry Abrams, Inc. New York, N.Y. 2000

America in Art, Fifty Great Paintings Celebrating Fifty Years, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1991

Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia

Frederick Carl Frieseke, The Evolution of an American Impressionist, Princeton University Press, 2001

Lecture Notes of Mary Louise Hinchliff, dated 1914

Chase Summer School of Art, Carmel-by the-Sea, California

(from Margaret Mallory papers)

Undated photo of Mr. Chase teaching a mens figure study class at the Chase School of Art, which he established, and later would become Parsons, The New School for Design.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

William Merritt Chase thought so highly of the sitter of this portrait, his student, Lydia Field Emmet, that he invited her to lead drawing classes at his famed Shinnecock Summer School of Art on Long Island. By the time he fashioned this elegant likeness, Emmet was a much sought after high society portraitist, who painted with a painterly bravado similar to that exhibited here by her famous mentor. Emmet’s aquiline nose, prominent chin, and mysteriously veiled gaze give visual expression to her self-possession, as an artist much in demand. Chase uses her all-black attire to luxuriate in the inky tone, which like his artist-hero Velázquez, he could subtly modulate with as much virtuosity as his nemesis, Édouard Manet.

- Preston Morton Reinstallation, 2022

I’ve scoured the internet, and haven’t found anything to suggest that Manet was a “nemesis” of Chase. My best guess is that the curatorial label is in error.

-Michael Wilk